A more contested space domain calls for better-prepared Guardians and faster responses to dangers in space.

The U.S. has been the dominant player in space for over 40 years. That has enabled commercial development of space capabilities to grow and thrive, freely and openly, both domestically and across much of the industrialized world. Today, a thriving global commercial space industry supports more than 60 nations in space.

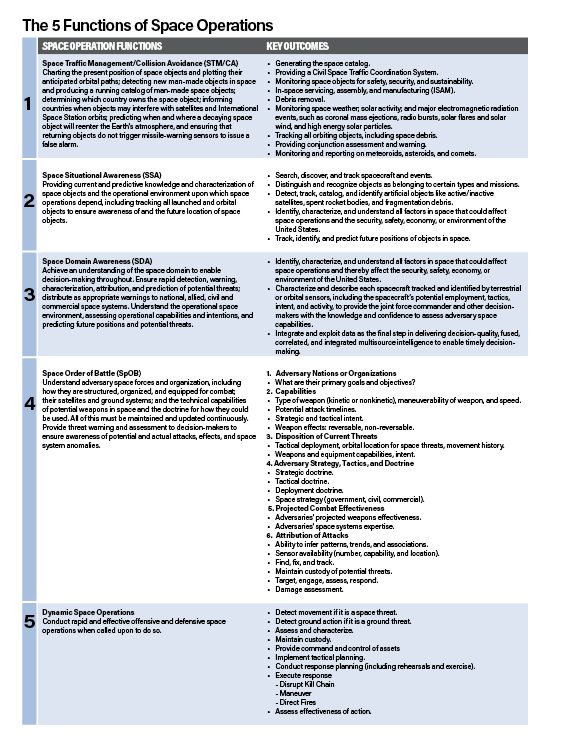

However, today threats in space are significant. Increasingly, U.S. space capabilities are contested, as Russia and China pursue threatening capabilities to challenge what was once U.S. dominance and have become near parity. Each has been provocatively demonstrating capabilities, announcing intent for a variety of individual space weapons and even deploying systems that challenge U.S. superiority in space. This means the U.S. can no longer simply provide the space situational awareness (SSA) needed for observing and tracking and the space domain awareness (SDA) necessary to determine intentions, capablilities, and behaviors, but must be ready to conduct a space battle at speed. This requires that we gain a full understanding of the entire space order of battle (SpOB) to underpin the ability to execute “Dynamic Space Operations” if these capabilities do not deter our adversaries.

Three years ago, Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall defined seven Operational Imperatives and listed “Defining Resilient and Effective Space Order of Battle and Architectures” at the top of his list. It was at once the broadest and most impactful of the imperatives, given that U.S. space capabilities are the foundation of America’s ability to project power not just beyond the Earth, but in every domain on Earth—air, land, sea, undersea, and even cyberspace. As Chief of Space Operations (CSO) Gen. B. Chance Saltzman said in March: “We see an incredibly sophisticated array of threats, from the traditional SATCOM and GPS jammers to more destabilizing direct-ascent anti-satellite weapons across almost every orbital regime, to on-orbit grapplers, optical dazzlers, directed-energy weapons, and increasing cyberattacks both to our ground stations and the satellites themselves.”

The Space Force’s chief of intelligence and the National Space Intelligence Center (NSIC) assess threats by evaluating the capabilities, performance, system limitations, and vulnerabilities of potential adversaries. Thus informed, the CSO is responsible for developing and tailoring the space capabilities U.S. joint forces need to ensure access to space for U.S. and allied operators and to ensure the U.S. can hold at risk the space capabilities adversaries depend on for their own military operations.

62 Years of History

Space has been a warfighting domain since 1962, when both Russia and the U.S. first pursued anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons. The Air Force’s Program 505 conceived of a prototype Nike Zeus anti-ballistic missile with a 1 megaton warhead to destroy potential space weapons threatening the U.S. Tests at White Sands Missile Range, N.M., began in December 1962 with dummy warheads. After several successful tests, the system was deployed to Kwajalein Island in the Pacific, where it remained operational until its retirement in May 1966. Program 437, a Thor-launched Direct Ascent ASAT missile, operated from June 1964 to May 1970; the system was tested at Johnston Island eight times, always without the nuclear warhead.

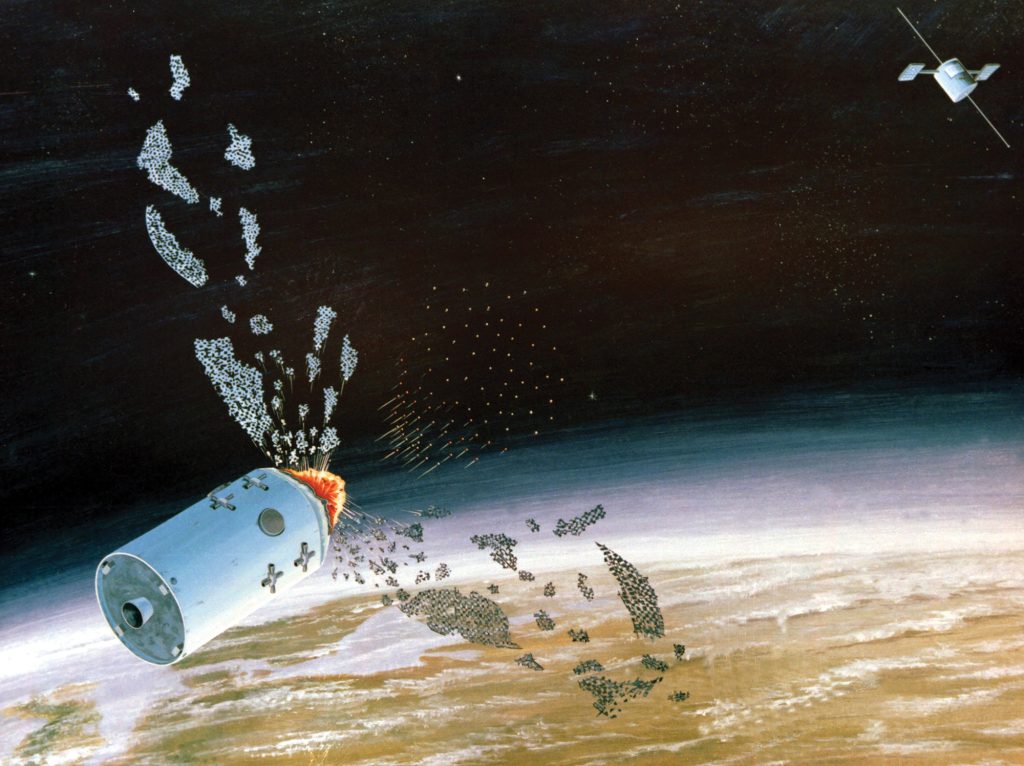

Russia developed and demonstrated a co-orbital kinetic satellite interceptor called the Istrebitel Sputnikov (IS-Destroyer of Satellites) from 1967 to 1983. The system used radar and a heat-seeking guidance system to get within 1 kilometer of its target, at which point it would deploy a shrapnel warhead to kill the satellite. In February 1970, the Soviet Union conducted its first successful intercept with the weapon, firing on the Kosmos 217 target. Some 23 launches, including seven intercepts, followed, and it was declared operational in February 1973. Each intercept created between 80 and 109 trackable fragments. Russia’s Polyus, Almaz, and Aryad ground lasers followed.

The U.S. military demonstrated the Airborne ASAT in September 1985. Since then, China, Russia, and India have demonstrated numerous on-orbit, direct-ascent, and ground-based weapons, all of which could potentially threaten U.S. satellites. In September 2006, China used a ground-based laser to dazzle a U.S. classified optical reconnaissance satellite, temporarily blinding the system. China and Russia have also attacked American space assets with cyber technology.

In those days, U.S. forces could provide only space traffic management and minimal space systems awareness, for collision avoidance from intentional threats. Over time, however, space situational awareness would grow, supported by sensors on the ground and in space. On Jan. 11, 2007, the Chinese anti-satellite missile test occurred. Then-Col. Stephen Whiting the Joint Space Operations Center commander noted, “We watched that test unfold over time, and we led the response for U.S. STRATCOM. We spent weeks and weeks figuring out how we would notify national leadership in real time. And those of us who were there, including then-Maj. Gen. Willie Shelton, Lt. Col. Chance Saltzman, and Maj. DeAnna Burt, knew the world had changed, on that day.”

We subsequently moved from SSA to SDA, which meant thinking about activities in space globally, rather than on specific systems in isolation. The threats affecting the space environment have advanced significantly since 2007 and by 2019, expanded to include ground-based lasers, signal jamming, direct-ascent weapons, co-orbital threats—some equipped with robotic grappling arms—and even threats of nuclear ASAT weapons in space. This (along with other threats of hypersonic missiles and fractional orbital bombardment systems), has raised the stakes enough that Congress saw the need for an independent Space Force, with its mission to “Secure our nation’s interests in, from, and to space.”

Joint Publication 3-14, Joint Space Operations, describes space as a region “defined by altitudes rather than a nation’s borders or latitude/longitudinal coordinates.” Beginning 100 kilometers (54 nautical miles) above mean sea level and continuing into deep space, this area of operations is virtually limitless. Today, we know that threats in space no longer just reside in Earth orbit. As we move to the moon and Mars, the competition with China will certainly continue, and because of the great distances, responses will become more complex. JP 3-14 specifically defines the near-term area of concern as “ex-geosynchronous (XGEO)” orbit—that is, beyond about 36,000 kilometers (about 19,000 nautical miles), to include cislunar space, lunar orbit, and the Earth-moon Lagrange points.

To ensure access to the XGEO environment for both commercial and exploratory objectives, the U.S. faces a challenge unseen since the struggle to ensure freedom of navigation across the Earth’s oceans. Like the seminal work of Rear Adm. Alfred Thayer Mahan, who defined the naval strategies and doctrine needed to secure our sea lines of communication over a century ago, we must now do the same to protect and defend our vast space area of responsibility.

Ready for War in Space

The United States would prefer to be in a state of competition with the People’s Republic of China and Russia rather than in crisis or open conflict. That requires deterrence.

In General Saltzman’s CSO C-Note 20, he lists current USSF goals and objectives to include “conducting low-intensity operations without compromising high-intensity readiness. The military of a great power must have the capacity to engage in protracted, day-to-day competition with its rival. Failing to do so cedes advantage and endurance. At the same time, a great power military must also prepare for high-intensity conflict, demonstrating the combat-ready credibility that underscores deterrence.”

He goes on to say the Space Force must develop a space warrior mindset via the following measures:

- The U.S. Space Force will need to be able to fight through disruption by improving defensive capabilities and increasing options for reconstitution, while assisting allies and partners in doing the same.

- Provide assured delivery of capabilities to our warfighters.

- Provide capabilities and tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) for suppression of enemy space capabilities.

- Shift from static to dynamic operations.

A space war could be very short, over in just 24 to 48 hours, because of the relatively limited number of key satellite assets both sides possess. A move to blind early warning, jam GPS and critical comm systems, and otherwise cripple critical space capabilities would likely occur with simultaneous or nearly simultaneous attacks. Therefore, the United States must be ready to fight and win a conflict in space within minutes of warning. To do so requires a comprehensive offensive and defensive space order of battle, to enable Guardians to fight dynamically with speed and exercised and rehearsed tactics, techniques, and procedures from the moment conflict begins.

There are two foundational elements to this approach: First, the Space Force’s posture and order of battle and capabilities available, and second, USSF’s ability to understand and monitor our adversaries’ posture, capabliities, and order of battle. The Space Force has made significant progress developing a resilient U.S. space architecture and space order of battle capable of operating while under attack. However, work remains in developing and understanding the U.S. space “dynamic offensive & defensive response” needed to rapidly respond to the potential actions of an adversary.

This requires a further evolution beyond space domain awareness to a full understanding of the “offensive and defensive” space order of battle. While we would obviously prefer to be in a state of competition with our adversaries, the risk of crisis or open conflict demands we prepare for the worst.

Competitive Endurance

In C-Note 15, General Saltzman defines his concept of “Competitive Endurance” as engaging strategic rivals long-term in pursuit of U.S. national interests without compromising the safety, security, stability, or long-term sustainability of the space domain. To do that, he wants Guardians to think critically, to challenge assumptions, test new ideas, share those ideas broadly, and to do these things with a clear sense of urgency.

“Our adversaries must never be desperate enough or emboldened enough to pursue destructive combat operations in space,” General Saltzman wrote in that forcewide note. “We must have the capability and fortitude to endure in a long-term state of competition because doing so is preferable to crisis or conflict in the domain. The goal of Competitive Endurance is to ensure our ability to achieve space superiority when necessary while also maintaining the safety, security, stability, and long-term sustainability of space.”

The Space Force must maintain “stability in Space and contest, deter and, when directed, fight in and control the space domain,” he wrote, in order to “assure delivery of capabilities to our warfighter—without interruption—and deny adversary space capabilities that threaten our warfighters.”

To achieve these goals, USSF must have the means to stop aggression before it starts; quickly respond at the time, location, and method of its choosing, and contain potential conflict before it grows into something worse.

To avoid operational surprise and prevent conflict in space, USSF must be able to “identify behaviors that become irresponsible or even hostile, and to detect and preempt any shifts in the operational environment that could compromise the ability of the joint force to achieve space superiority.” This means not just knowing when adversaries make a move, but also understanding the implications of the move and the TTPs available to counter it.

The predictability of orbits gives the offense a particular first-mover advantage in space, which is why resilience—that is, the ability to take losses, adapt, and survive despite an attack—is crucial to denying that first-mover advantage. The United States must be able to absorb losses and continue to operate, leveraging responsive launch capabilities that enable USSF to rapidly restore or reconstitute degraded capabilities. Strong offensive and defensive capabilities will allow us to defend against attacks and to conduct attacks of our own, if warranted. The Space Force strategy today seeks to make an attack on satellites impractical, even self-defeating, to discourage adversaries from taking such actions in the first place.

Deterrence can come in both offensive and defensive forms. Offensive deterrence discourages threats by holding selected adversary space capabilities at risk using means that will neither destroy nor damage the space environment. The offensive TTPs need to have been rehearsed and the operations team prepared to implement in a pre-approved fashion so that we can operate at the speed of our adversaries.

Defense can also deter aggression in space, through the ability to defeat threats by overcoming them without being destroyed. With the speed of activities in space, we need to have defensive responses that we have rehearsed and exercised immediately available to our space operators. A third form of deterrence is resilience: Both proliferated constellations that can absorb losses without impact to operations and responsive space, with which lost capabilities are rapidly reconstituted can provide a deterrent effect.

Offensive and defensive space operations may be necessary to prevent adversaries from leveraging space-enabled targeting to attack our forces—but we must balance our counterspace efforts with the need to sustain allied space assets in every orbit. We must protect the joint force from space enabled targeting, while simultaneously understanding that we cannot have a Pyrrhic victory in this domain. In other words, efforts to control the domain cannot inflict such a devastating toll on the domain itself, that our orbits become unusable for operations. The critical element in this battle will be speed, and this needs to be built on a foundation of understanding and being prepared built upon a robust SpOB.

If we cannot stop an adversary from being the first to move, we must be prepared to be faster in our responses than they will be in their aggression. We cannot take time to contemplate the situation, or the war will be over before we can act. We must understand where all the potential threats are and have exercised and rehearsed responses with well-trained Guardians. If we cannot stop an adversary from being the first to move, we must be prepared to be faster in our responses than they will be in their aggression.

Competitive endurance, therefore, is the driver to a more robust understanding of our adversaries and the need to evolve from domain awareness to a clear understanding of the space order of battle.

“Do we have the tools that pull data together and contextualize it, so decision-makers can make timely, relevant operational decisions?” General Saltzman asked, in a rhetorical challenge to industry at the Mitchell Institute’s Spacepower Security Forum in March. The Space Force needs “tools that actually make the most out of the data that we are collecting and will be able to take on even more data and make more sense of it faster,” he added. “We cannot, as a country or a service, miscalculate the capabilities, force posture, or intentions of our potential adversaries. We must have timely and reliant indications and warnings to help us avoid operational surprise in crisis where appropriate to take defensive actions.”

Space operators must be able to quickly tell the difference between routine operations like refueling, refurbishing, and debris removal from potentially hostile activity, such as detecting the start of a kill chain. Timely and relevant SpOB should help avoid operational surprise in crisis and, when appropriate, dynamic offensive or defensive actions to counter adversarial moves.

As part of the new “warrior mindset” Lt. Gen. John E. Shaw, deputy commander, U.S. Space Command, and Gen. Michael A. Guetlein, vice chief of space operations, have discussed a shift from static to dynamic space operations (DSO). U.S. adversaries are now deploying satellites that can maneuver and rendezvous with other objects, which puts the U.S. at a disadvantage.

U.S. Space Command has stated the importance to be able to maneuver without regret and that dynamic space operations, maneuvering satellites, and refueling support would give the military options to better defend its assets in space by:

Putting additional focus on attribution of malicious actions within the space domain or against space architectures, including how allies and trusted commercial partners can participate in attributing irresponsible or threatening behaviors toward their own space assets.

Cultivate partnerships to build advantages. For example, hybrid space architectures incorporating U.S. government, allied, and commercial satellites—while spanning multiple orbital regimes—can help disincentivize an adversary’s potential attack.

Build on changes made to implement a mission planning crew commander (who is dedicated to effects-based dynamic mission planning), so that we can better orient forces when it comes to space battle management. This member pairs resources (sensor network) to support a healthy space picture in support of current/future ops.

Implement mission type orders, where we can hone sensor specific effects to better capitalize on intentional planning, and to measure the effectiveness of those mission plans. This would help build the initial space picture on the aggregate level for operations.

Finally, in coordination with other U.S. departments and agencies, the Space Force must increase collaboration with the commercial space industry, leveraging its technological advancements and entrepreneurial spirit to enable new capabilities that support integrated deterrence. However, as the Space Force inevitably involves commercial space assets in tactical surveillance, reconnaissance, and tracking, and gathering SSA data and developing SDA data to support our SpOB capabilities, we need to be fully cognizant that we must protect these assets as if they were USSF assets, whether these be civil or commercial. Commercial space systems contributing to the defense of Ukraine have been declared by Russia as legitimate targets, and if we use them, we need to be prepared to defend them.

The new USSF Doctrine (SDP 3.0-July 2023) states the Space Force will undertake operations in three “baskets:”

Shape the Operational Environment. Space operations include activities to promote security and stability, preserve freedom of action, and deter adversary activities to the contrary. Space Force communicates with other DOD and Intelligence Community organizations, while building relationships with allies, partners, commercial entities, and academia. Along with data sharing and collaboration, where appropriate and authorized, these relationships help build support for operations in all domains, increase overall security in the space domain, promote appropriate behavior in space, and deter adversaries.

Prevent Conflict. Space operations to prevent conflict in, from, and to space include all activities to deter undesirable actions by an adversary. Space operations enhance safety and security of Joint operations and deterrence in all domains. As part of the joint force, the Space Force is focused on actions to deter dangerous or unlawful adversary behavior in all domains through a range of reversible and non-reversible effects.

Prevail in Combat. Should deterrence fail, the Space Force is prepared to enable lethality and effectiveness of the joint force by delivering space combat power to ensure the United States prevails in conflict. Space Force, as part of the joint force, will take actions to deter undesirable adversary behavior and deny, disrupt, damage, or destroy adversary space capabilities across all domains. Planners may also consider deceptive operations with appropriate authorities.

Responsible Counterspace Campaigning

“If a near peer competitor makes a movement, we need to have it in our quiver to make a counter maneuver,” said General Guetlein, in January. “Tactical relevance could mean acting within minutes or just a few hours, not a day.”

In a paper titled “Dynamic Space Operations” published in AETHER, the Journal of Strategic Airpower and Space Power’s Winter 2023 edition, the authors make the case for better space maneuver capabilities as a key element in both offensive and defensive dynamic space operations.

The authors argue for decentralized execution to create “reversible decisions that can be pushed to lower levels with less risk and opportunities for more expansive and resilient use of artificial intelligence (AI) and autonomy.” The payoff, they said, “decreases response times and increases the ability to improvise and pursue fleeting opportunities.” Given the speed of potential space wars, there is little time to go up and down the chain of command.

The paper also argues for preparedness. “Improved readiness enables routine and robust live training with on-orbit forces without sacrificing long-term mission success,” they wrote. “It establishes better avenues to reversibly explore new operating concepts, provides more robust testing opportunities for new systems and tactics, improves deterrence through demonstrated strength, and ensures capabilities can be quickly reconstituted to deter opportunistic third parties.”

To achieve these objectives, the U.S. should normalize space and treat it as any other warfighting domain. That means clearly and unambiguously stating a willingness to conduct both offensive and defensive space operations, including both “direct capabilities”—that is, “fires that impact an adversary”—and maneuver. U.S. Space Command is the combatant command responsible for such operations.

To make sound strategic and tactical decisions, USSF will rely heavily on its deep knowledge of the characteristics and current state of the Space AOR, both from LEO to GEO and beyond to XGEO (specifically cislunar) and intelligence regarding our adversaries’ capabilities both in space and on the ground.

Consideration of the natural environment of space, coupled with its current congested nature, implores us to keep track of what is there and what those objects are doing, which includes a growing amount of uncontrolled space debris. It is however, the adversaries that are of greatest concern, and information about their space capabilities and intent is difficult to obtain and process. This information is precisely the space order of battle that Space Command needs to be effective. SpOB refers to the intelligence and knowledge of any military force involved with the Space AOR. This includes not only our enemies or potential enemies, but also friendly and neutral forces since debris and inadvertent actions can cause misunderstandings in space.

Since our beginnings in space, it has not been a benign environment. While mostly unknown to U.S. citizens, provocations and dangerous tests have occurred from the major powers to assert their dominance over the domain. Demonstrating offensive space capabilities have damaged the environment of space, and since the provocative Chinese test in January 2007, things have become more and more dangerous.

This does not necessarily mean there will be a space war, but it has become a possibility. Like the first Space Race based on nuclear missile capabilities, deterrence will be critical in averting a space war. China and Russia must be convinced that a space war cannot be won by them. Toward this end we must demonstrate to them we can operate at the potential speed of a space war. Moving to SpOB and dynamic space operations will assure that, buoyed by constant training and delegated T&T’s that can be executed at the speed of a potential space war, and this will deter that terrible event from occurring.

Thomas “Tav” Taverney is a retired Air Force major general and former vice commander of Air Force Space Command.