Why retiring the B-1 too soon could undermine U.S. security.

The U.S. Air Force plans to start retiring the B-1 Lancer fleet to make room for the new, sixth-generation B-21 Raider. But the Air Force is planning to do that before the B-21 is combat-ready, a move that threatens America’s long-range strike capability and capacity.

The Air Force’s future bomber force will be composed of only the B-21 and the 1950s-era B-52 Stratofortress. Although the future of America’s bomber fleet may appear secure, there are significant reasons for concern. The early retirement of the combat-proven B-1 is being driven by budgetary decisions, instead of U.S. warfighting needs and sound threat-risk assessments. Geopolitical instability is rampant and global bomber demand is at its highest ever, yet the bomber fleet is forecast to dive into instability and shrink before it can grow. The repercussions for U.S. national defense strategy and global power projection could be catastrophic.

The Critical Value of Long-Range Strike

The phrase, “long-range strike” has been echoed recently by many senior Air Force leaders, specifically within the context of strategic competition with China. As demonstrated by the February 2024 B-1 strikes against Iranian-aligned targets in Iraq and Syria and the October 2024 B-2 Spirit strikes in Yemen, the Department of Defense can use long-range strike to quickly and precisely project global power from the U.S. homeland. These short bursts of power showcased America’s ability to secure strategic objectives while also grabbing the attention of every adversary the U.S. lists in its National Defense Strategy. Blared over global media outlets, adversarial nations were immediately reminded of a capability they do not possess, and that the U.S. can use at times and places of its choosing.

In recent years, the Air Force has conducted long-duration Bomber Task Force training missions where bombers, predominantly B-1s and B-52s, execute non-stop flights from the continental U.S. to the Indo-Pacific, Europe, Middle East, or elsewhere, then land back at their home base. With flight durations often over 24 hours, these operations are taxing on the aircrew and base support teams, but they are crucial to forging bonds with allied militaries. Often featuring training integration with U.S. allies and partners, the long-duration missions also serve as strategic deterrence messaging. This reminds potential adversaries to avoid hostile actions that could lead to conflict against the U.S. and its partners. Behind the scenes, these missions are challenging to plan and execute because of the complex coordination required among different U.S. military command levels and partner nations. Despite the challenges and complexities of these operations, the Air Force has unequivocally proven its ability and proficiency in long-range strike.

With U.S. forces stationed all over the world, why is long-range strike so necessary? The answer: China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea continue to produce conventional and asymmetric weapon systems designed to keep the overseas U.S. military under threat, especially those U.S. forces in the Indo-Pacific theater. Long-range strike capabilities counter those weapons because they can generate mass combat power from relatively safe locations, often thousands of miles away.

Why Keep the B-1?

Global power projection with long-range bombers is something no other nation can currently execute, and while the B-2 and B-52 are both capable of long-range strike missions, the B-1 “BONE” brings unique value to the Air Force arsenal.

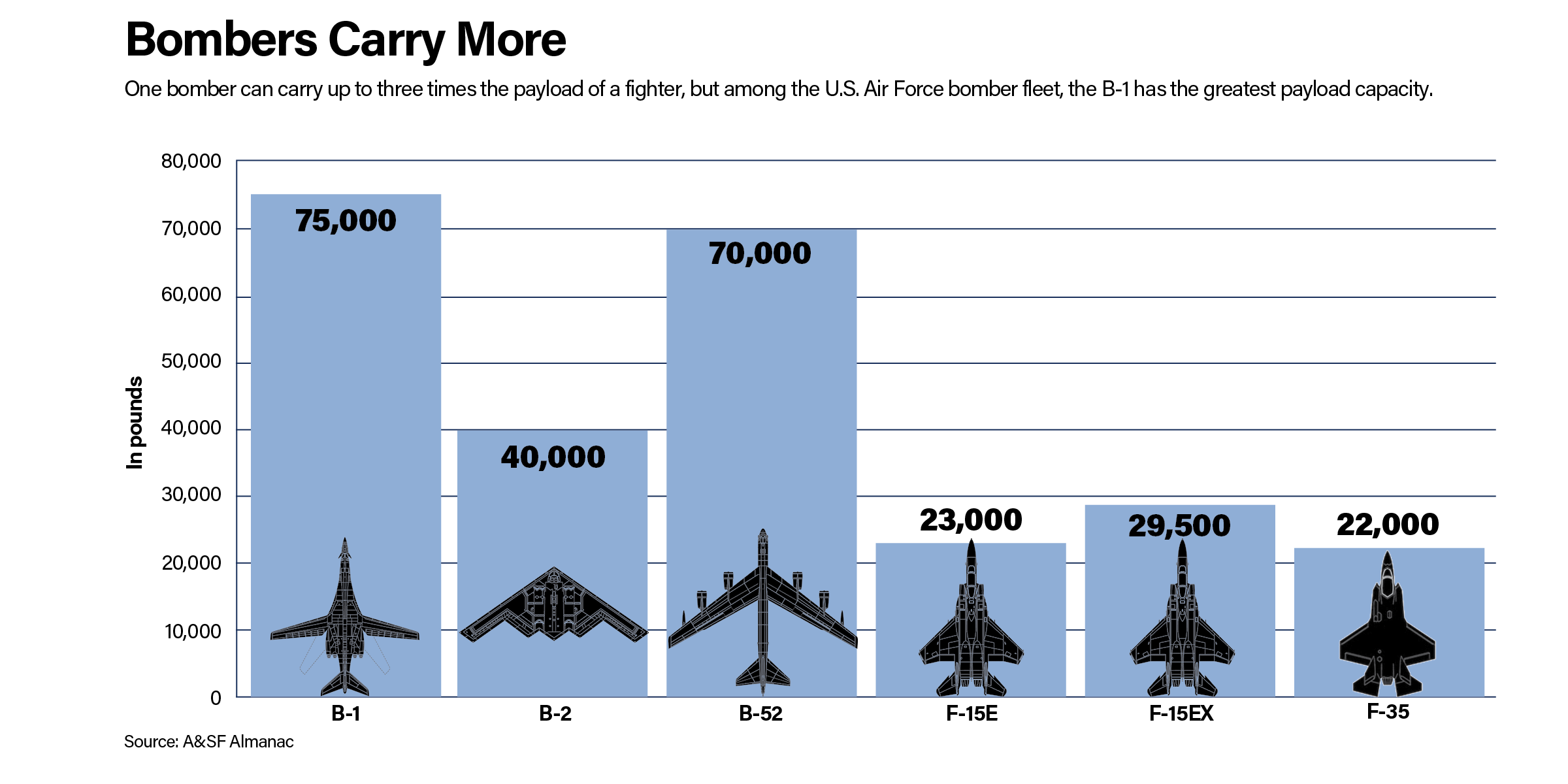

The B-1 has flown over 12,000 combat missions since 2001. As the only supersonic and swing-wing bomber, it also carries the largest payload of precision and nonprecision weapons of any U.S. aircraft. Affectionately known as the “Roving Linebacker” in the Middle East, coalition forces relied heavily upon the B-1’s immense weapons payload, range, flexibility, and speed during operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. Notably, the B-1 flew only 2 percent of combat missions over Afghanistan, yet was responsible for over 40 percent of precision weapons released on enemy targets; the trend continued over Iraq and Syria during Operation Inherent Resolve. Despite the B-1’s unmatched track record with combat operations in the Middle East, the Air Force stopped continuous B-1 rotational deployments, giving the aircraft and personnel the opportunity to recover from the toll of nearly two decades and thousands of flight hours in combat. With concerns over B-1’s aircraft structural service life and increasing national focus on the Indo-Pacific, the Air Force directed the B-1’s transition into its newest role, strategic deterrence and assurance.

For regional combatant commands, like U.S. European Command and U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, the B-1 has become a mainstay of Bomber Task Force deployments, providing a tangible deterrent effect. The B-1 stands apart from the other bombers, thanks to its basing flexibility, weapon diversity, speed, range, mission set agility, and non-nuclear messaging. With the Pentagon’s emphasis on “great power competition” in the European and Indo-Pacific theaters, the B-1 community’s focus is aligned to its primary purpose—strategic attack—specifically with standoff weapons.

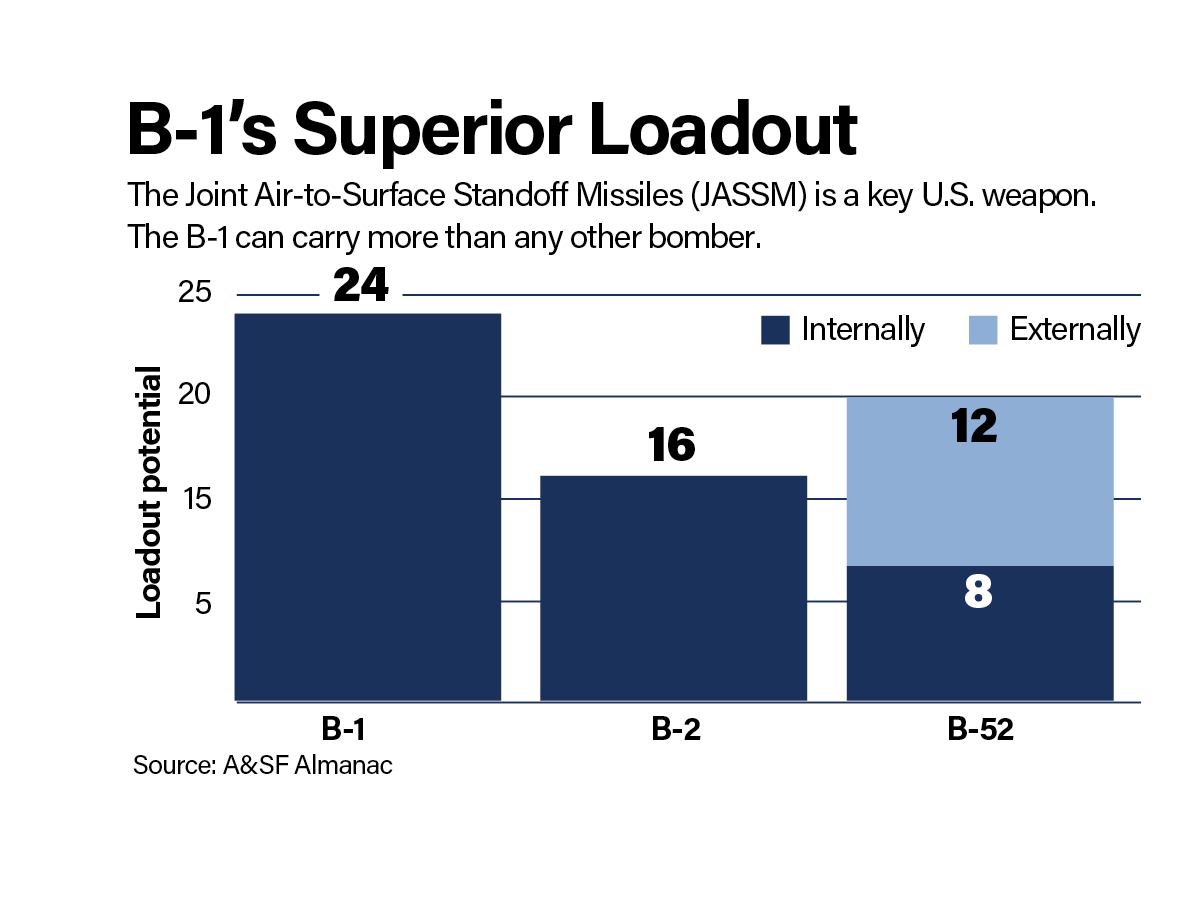

The B-1 not only has the largest weapon payload of any U.S. aircraft, it is also the Air Force’s testbed bomber for hypersonic weapons, making it a supersonic standoff-missile truck ready for future conflicts. Equipped with the Air Force’s most exquisite missile, the AGM-158 Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM), B-1s are capable of engaging enemy surface targets from over 500 miles away. A B-1 can carry 24 JASSMs per aircraft, and development is underway to allow for future external carry capability for a maximum potential loadout of 36. For context, a single B-1 brings more AGM-158 missiles to a conflict than either a B-2 or B-52, and as many as 12 single-seat fighter aircraft. Notably, the B-1 is the only Air Force aircraft currently capable of carrying the maritime version of the AGM-158, known as the Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM). This missile is designed to accurately target enemy combatant ships that create anti-access/area denial challenges for the U.S. military. With China and Russia expanding their navies, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command and U.S. European Command will need the maritime version of the AGM-158 and the B-1 as key warfighting enablers for any potential conflict in the near-term. Until the other bombers can employ the maritime AGM-158 and also provide the same level of combat effects as the B-1, the U.S. military should be unwilling to surrender the warfighting capability the BONE brings to bear.

A multitude of U.S. allies and partners, especially in the Indo-Pacific theater, rely on the B-1 for strategic messaging, which is foundationally based on its credible combat capability as a non-nuclear bomber. Partner nations clammer at the opportunity to join in with the B-1 on strategic deterrence efforts aimed at China, North Korea, Russia, and Iran. A significant component to U.S. strategic-level messaging with the B-1 is its lack of nuclear weapon capability, directly contrasted to the B-2, B-21 and B-52, which are all nuclear weapon-capable platforms. For many partner nations, especially Japan, one of America’s strongest allies in the Pacific, the lack of nuclear capability makes the B-1 a preferred option. But if the B-1 is retired, America’s only nonnuclear bomber messaging option will be gone.

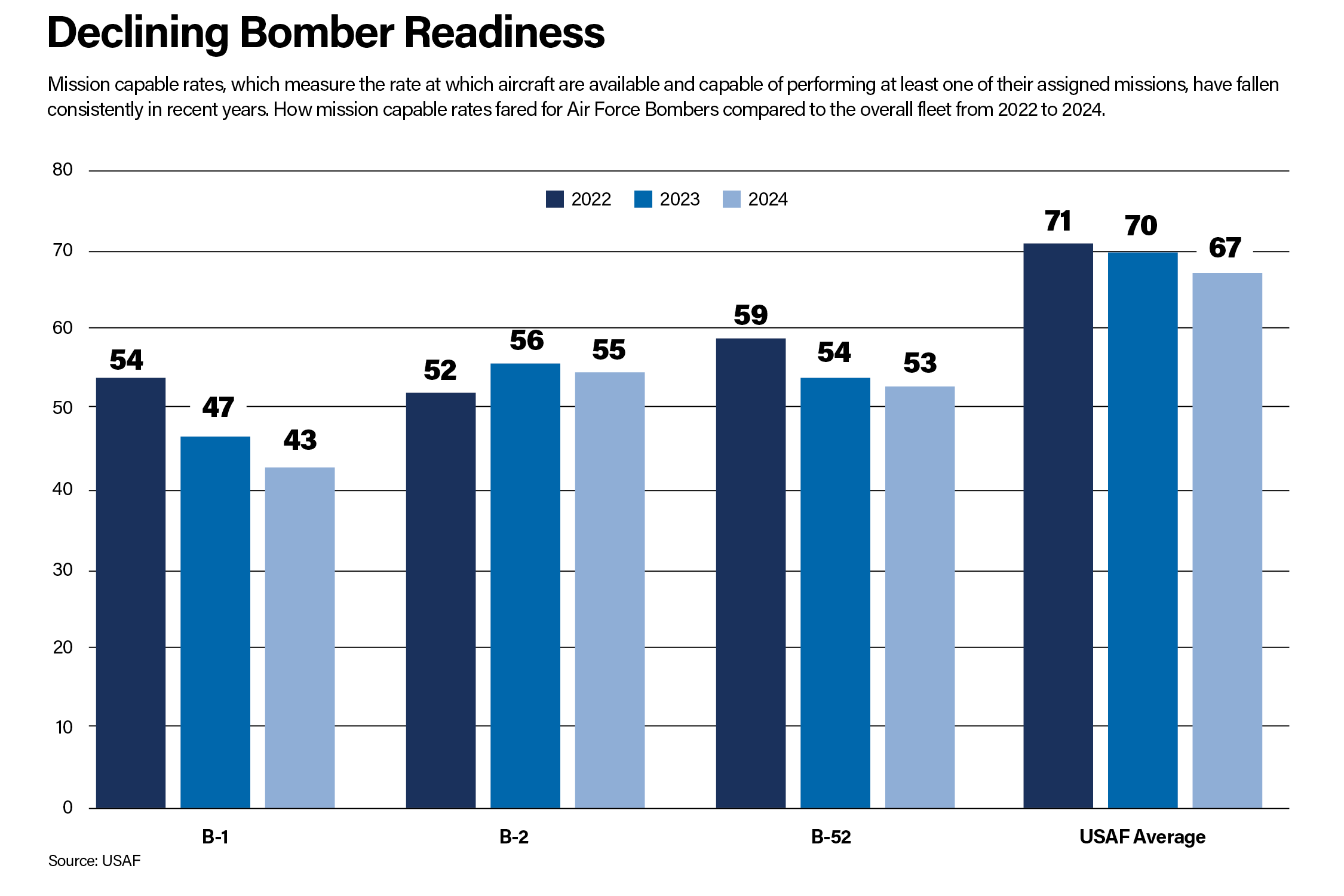

Critics of the B-1 often state two major concerns: maintenance and survivability. As the B-1 fleet approaches 40 years old, these are major concerns the Air Force has to confront, but the B-1 is not alone in this discussion.

With the B-52 fleet over 60 years old and the B-2 fleet approaching 30 years old, the Air Force’s bombers are all struggling with maintenance issues, mostly driven by supply chain gaps, and current-day relevancy to evolving threats in the 21st century. According to data provided by the Air Force for 2022 to 2024, the B-1’s maintenance rate, also known as mission capable (MC) rate, is consistently similar to the B-2 and B-52. Historically, all three bombers have rates lower than the USAF average. In 2022, the B-1’s MC rate was higher than the B-2 rate and matched the B-52 rate for 2023. Compared to the rest of the Air Force, the B-1 MC rate for 2023 was higher than the C-130H, C-5M, CV-22, EC-130H, and F-15C. Surprisingly, the B-1 rate for 2023 was only 4 percent lower than the Air Force’s newest fighter, the F-35, and in 2024, the B-1 MC rate was reportedly higher than the F-22. Ultimately, the B-1’s maintenance generation capabilities are not as terrible as critics often reference, but it is a complex aircraft that does require a lot of maintenance time and cost.

For survivability, the B-1’s combination of evolving tactical procedures, ability to fly at supersonic speeds, maneuverability, and recent aircraft upgrades, make the B-1 survivable against the U.S.’s peer and near-peer adversaries. Although the B-1 is not a stealth aircraft like the B-2 or B-21, the B-1 does not need to be. In the opening days of major combat operations, the B-1’s most likely weapon employment would be with AGM-158 standoff missiles, released hundreds of miles away from enemy threats, thereby reducing the requirement for stealth.

The Plan for Instability

China’s President Xi Jinping has declared 2027 the year by which his forces should be “ready” to execute a potential military invasion of Taiwan. That means, the stability of America’s bomber force over the next five years is paramount. Yet at a time when the U.S. faces the greatest generational threat to its global security, the bomber force is becoming unstable due to planned retirements of the B-1 and B-2, the introduction of the B-21, and the major overhaul planned for the B-52. On top of this, the Air Force is also facing an unresolved aircrew retention crisis, funding shortfalls and force structure changes, leading to a future fraught with challenges.

The Air Force’s only publicly released timeline for B-1 retirement suggests the aircraft will be retired no later than 2036. But with the rollout of B-21s to Ellsworth Air Force Base, S.D., starting in the mid-2020s and the Air Force’s aircrew manning struggles leading to efforts to stay “manning neutral,” the divestment of B-1 aircraft could start as soon as 2026. This timeline likely puts B-1 aircraft moving into retirement before B-21 flight-testing is completed at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., and well before the first B-21 combat squadron is operational. Based on previously seen Air Force practices, it is likely an entire B-1 squadron of 10 aircraft will be inactivated at once, directly cutting the combat-ready B-1 fleet by 30 percent. At the same time, the B-52 will start its biggest upgrade in decades, which the Government Accountability Office (GAO) reports will last until 2035. As the 76 B-52H aircraft go through two major upgrades to their RADAR and engines, fleet availability and mission-generation capabilities are forecast to drop 20 to 25 percent over the next eight years. For several years, the B-2, with a small fleet of 19 aircraft, will be the only stable bomber platform in the inventory.

Global demand for bomber presence and operations has increased significantly over the past 10 years, by one estimate 1,100 percent. During a recent Mitchell Institute interview, Gen. Thomas Bussiere, commander of Air Force Global Strike Command, emphasized this point by saying, “The demand signal for the bombers is greater than any time I’ve seen in my career, across the fabric of every geographic combatant command.” Because of security concerns surrounding the stealthy B-2, B-1 and B-52 squadrons have historically executed most bomber deployments and missions.

With the B-21 likely to require its own special security protocols, the divestment of B-1 aircraft will leave most of these requirements to the B-52, which will either overwhelm an already overtaxed B-52 community or force the Air Force to drastically cut back its global bomber missions. The Air Force’s decision to retire the B-1 early shines a spotlight on a troubling disconnect between America’s global security requirements and the size of its Air Force in general, and its bomber fleet in particular.

The Air Force plans to purchase at least 100 B-21s, with the goal of operating a total of 175 bombers; the Mitchell Institute, among others, has recommended doubling the B-21 fleet to at least 200, noting that USAF’s goal of 175 bombers in 2040 is too little for the requirement. Some Air Force senior leaders now agree that 175 bombers will likely not be enough for a major conflict against China or Russia. For context, the Air Force had 351 bombers in 1990 for Operation Desert Storm and 181 bombers in 2001 for Operation Enduring Freedom. Considering the Air Force’s track record for achieving its objectives for new aircraft—such as purchasing only a quarter of its originally planned F-22 fleet—and the slow delays that plagued the F-35 and KC-46 acquisitions, it is reasonable to question the Air Force’s ability to match its B-21 delivery objectives.

The Air Force’s final number of bombers and exact timeline are contingent upon the B-21 being delivered on time, on cost, and in full. As B-1 aircraft are retired and B-21s are slowly delivered, the Air Force’s bomber force will likely experience a “bathtub effect” where a drastic decrease in the total number of bombers occurs before it starts to increase above the current total of 141. This effect will also carry over to aircrew training and combat readiness as they transition from the B-1, B-52, or B-2 to become proficient in B-21 operations. Ultimately, unless actions are taken now to minimize the “bathtub effect,” there will be a multi-year decrease in U.S. bomber capacity to respond to aggression from China, Russia, or other adversaries. Delaying B-1 retirements until after the B-21 reaches initial operational capability (IOC) is one way the Air Force can hedge against the risks associated with onboarding of the B-21.

The B-1 and B-21 can operate together. This can be achieved by maintaining the current B-1 fleet at Ellsworth, even as the new B-21s show up and begin flying there. The Air Force’s divestiture of 17 B-1s in 2020 and 2021 unintentionally provided a benefit: There is now sufficient room for both the remaining B-1s and the B-21 fleet at Ellsworth. Alternative options include relocating B-1 squadrons from Ellsworth to Mountain Home Air Force Base, Idaho, where B-1s were previously stationed until 2002; or relocating the B-1 squadrons to Dyess Air Force Base, Texas. This would create a single B-1 center of excellence, similar to the B-2 wing at Whiteman Air Force Base, Mo.

A Bomber is a Bomber?

Each U.S. geographic combatant command depends on unique attributes of the B-1 that are at risk of disappearing in the coming years, without a notable replacement. Perhaps, at the core of this disconnect is the misguided generalization that “a bomber is a bomber.” Just as the F-22 and F-35, while both fifth-generation fighters, are not fully interchangeable, each bomber brings unique capabilities and mission roles to the fight. The B-1 and B-21 are designed for different missions and roles, and offer different capabilities. While the B-1 lacks the B-21’s stealth and advanced warfare attributes, it offers superior speed, payload, and flexibility. The Air Force’s plan to swap the older, yet still capable B-1 for the fledgling B-21 will undoubtedly leave U.S. combatant commands scrambling to fill capability gaps.

Follow the Money

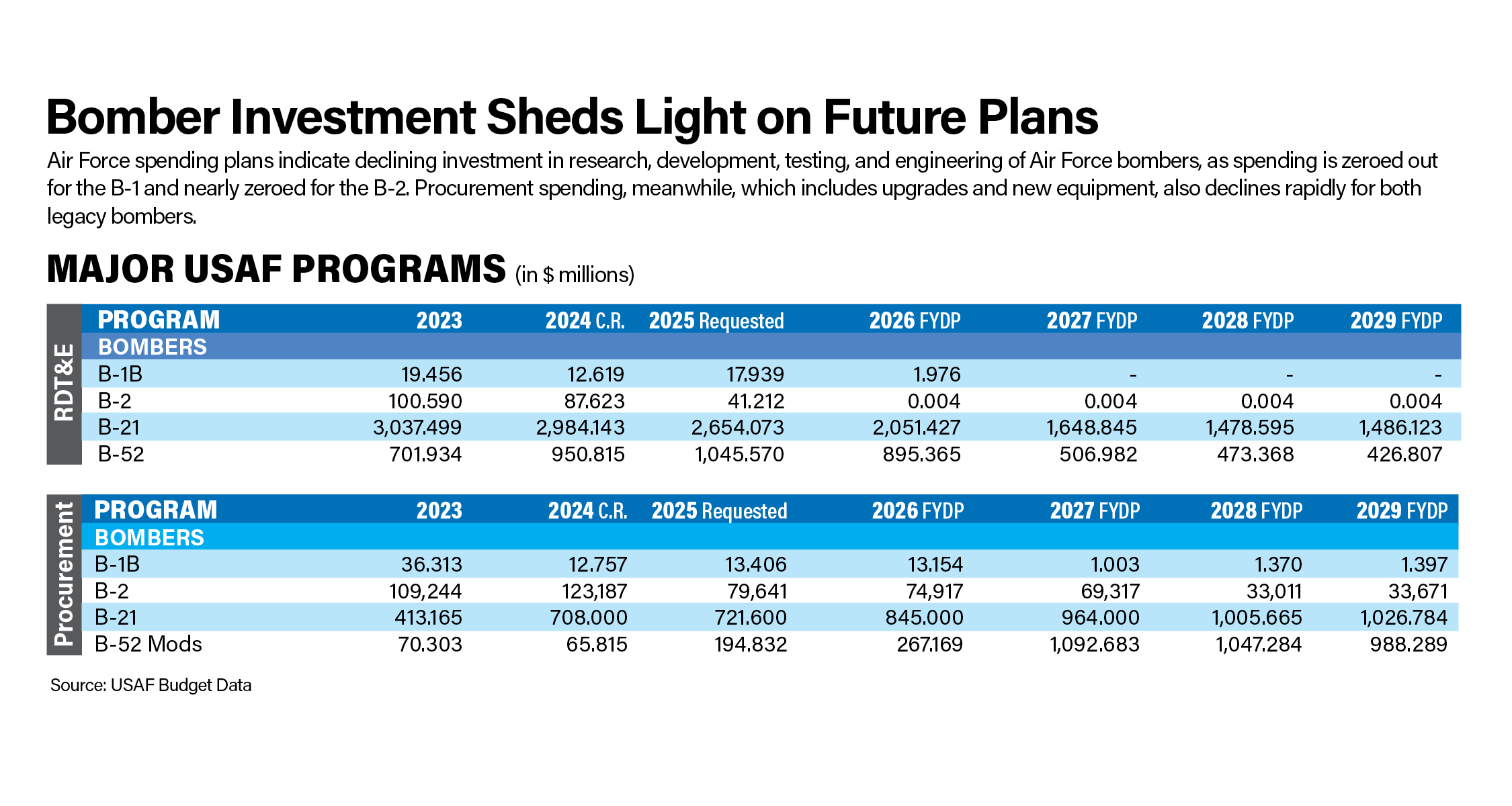

As the colloquial phrase goes, “follow the money.” With the U.S. military and its programs, words do not matter, allocated funding does. Every year, Congress approves each military service’s budget request and within those budgets are specifically allocated funds for different programs. Despite an Air Force senior leader recently announcing that “the B-1 and B-2 fleet retirement will be conditional,” the Air Force’s budget plan says otherwise. The Air Force’s Future Years Defense Program (FYDP) developed for fiscal 2025 to 2029 shows the stark truth that B-1 funding could drastically decline starting as soon as October of this year.

The funding for B-1 research, development, testing, and evaluation will sharply decline by 95 percent starting Oct. 1, 2025 (at the beginning of fiscal 2026) and end outright in fiscal 2027. As it was for the A-10 and other cut programs, such a large drop in funding marks the Air Force’s intentional “beginning of the end” for a platform. Additionally, funding support for B-1 weapon system procurement will fall 92 percent at the start of fiscal 2027. These changes in the Air Force’s budget, coupled with the Pentagon’s proposed force structure changes, strongly indicate B-1 retirements will likely start as soon as 2026.

Defenders of the Air Force’s budget decisions may argue “the B-1 is too expensive to operate,” but the U.S. GAO’s Weapon System Sustainment report shows the B-1’s operating costs are hardly unique. The B-2, on top of a per unit cost over $1 billion, is also extremely expensive to operate and sustain. The B-21’s future operating and sustainment costs are still unclear, but at $692 million per aircraft (2022 dollars) and the cost of maintaining a stealth aircraft, the future bomber will not be cheap. While the B-1 may be expensive, the alternative—not having the B-1 for a future conflict against a peer or near-peer adversary—is worse. The Air Force would be wise to consider seeing beyond program unit cost and see what matters most—“cost per effect.”

Recommendations

As the U.S. Air Force moves forward with B-1 retirement before the B-21 is ready, the Department of Defense is on the precipice of losing significant long-range strike capability and capacity. This decision will inherently have direct and consequential effects upon America’s military and diplomatic ability to respond to global threats. Many of the U.S. combatant command requirements will go unmet, while adversary deterrence and partner nation confidence in the U.S. will decrease during this generation’s greatest threat of geopolitical instability. If the Air Force expects to meet U.S. national defense, global security, and combatant command requirements between 2025 and 2035, it should consider the following actions:

Delay B-1 divestment and retirement until 2035, maintaining bomber fleet stability and U.S. warfighting capacity during a likely unstable geopolitical time.

Sustain funding for the B-1 at a level that will ensure technological relevancy until 2035, aligning the Future Years Defense Program to America’s national security strategy, which requires long-range strike capability.

Maintain the full B-1 fleet of 45 aircraft until the B-21 has achieved, at a minimum, initial operational capability status—proving combat readiness.

Conduct an official requirements analysis with the combatant commands to determine what specific capabilities and mission roles the B-1 is expected to provide during a major conflict, with emphasis on roles the B-21 and B-52 cannot perform.

Fund and deliver solutions from the requirements analysis for the B-21 and B-52, before the B-1 is retired, to ensure U.S. bomber response capability is sustained for all combatant command requirements.

Lt. Col. Ross “RAW” Hobbs is an Active-duty Air Force officer and Air War College student completing a Senior Developmental Education Fellowship. He is a former B-1 squadron commander, USAF Weapons School graduate, and Joint All-Domain Strategy graduate from Air Command and Staff College. A Command Pilot with over 2,600 flight hours in the B-1 and T-38C, including 466 combat hours, he has deployed five times and completed missions in support of Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Inherent Resolve, Continuous Bomber Presence, and Bomber Task Force. His work has previously appeared in the Over The Horizon Journal, War on the Rocks, and RAND publications.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect official policy or positions of the Department of the Air Force, or any other part of the U.S. government.