To the Army, its newest branch was both a trial and a source of strength.

This story was originally published Sept. 1, 2020.

In 1934, Maj. Gen. Hugh Drum, Army deputy chief of staff—the second-ranking officer in the Army—said there was no reason for airplanes to fly further than three days’ march ahead of the infantry.

Drum said there should be “no operations not contributing to the success of the ground campaign” and that independent air operations “would likely be wasted and might be entirely ineffective.”

The Air Service had been a combatant branch of the Army since 1920 and was reorganized as the Air Corps in July 1926. It was—supposedly—on an organizational par with infantry, armor, artillery.

However, not all branches were equal. Army doctrine, as laid down in March 1914, identified infantry as “the principal and most important arm,” with artillery and cavalry in support. That order was still in effect. In 1926, the Army declared that the mission of air units “is to aid the ground forces to gain decisive success.”

In the 1930s, it became increasingly difficult for the Army to keep its energetic Air Corps on a short leash in view of the great leap in capabilities and importance of airpower.

Operations not contributing to the success of the ground campaign would likely be wasted and might be entirely ineffective.Maj. Gen. Hugh Drum

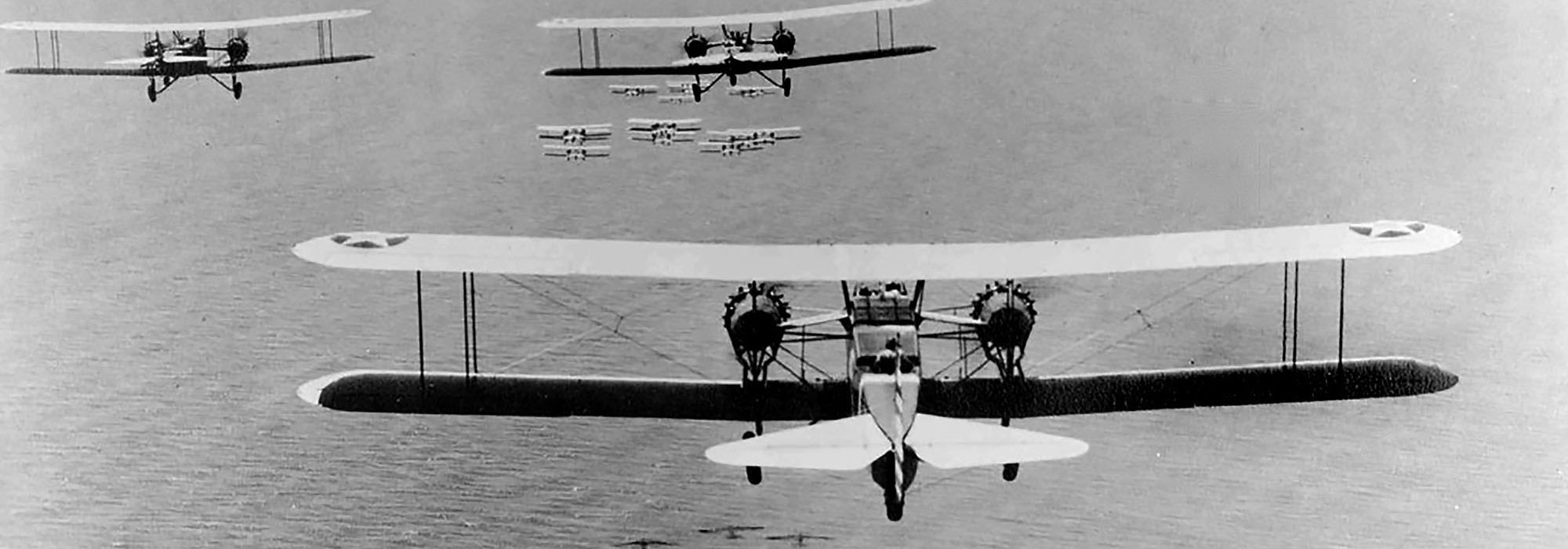

At the beginning of the decade, the best Air Corps bomber was the Keystone B-3A, a fabric-covered biplane with a cruising speed of 98 mph and a top speed of 114 mph. The P-26 “Peashooter” fighter, which entered Air Corps service in 1933, had an open cockpit and fixed landing gear.

The rapid advance of aeronautical progress made a huge difference in a few years. By 1939, the B-17 Flying Fortress was in service and had completely redefined the range and scope of warfare. The P-40 Warhawk was in production, and the P-51 Mustang was almost ready for flight-testing.

The Air Corps had begun to gain some acceptance in the early 1930s, conditional on a supporting role within the Army. When budgets were driven down by the onset of the Depression, much of the criticism of airpower focused on cost rather doctrine or precedent.

It could have been worse. The Air Corps budget declined every year from 1931 to 1934, but then recovered enough to grow in funding, personnel, and aircraft every year from 1935 to 1939.

A negative attitude toward air power—especially the B-17 bomber—was resurgent among Army and War Department leaders in the middle 1930s, and did not abate until the appointment of Gen. George C. Marshall as Army Chief of Staff in 1939 and Henry L. Stimson as Secretary of War in 1940.

The critical support was from President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who said, “I know of no single item in our defense today that is more important than a large four-engine bomber.”

The Junior Branch

The Army Reorganization Act of 1920, which made the Air Service a combatant arm of the Army, gave the rank of major general to the chief of the Air Service. Tactical air units were placed under the nine Army corps area commanders to be employed primarily in support of ground forces.

The Air Corps Act of 1926 basically changed the name to the Air Corps and gave it control of training, materiel, engineers, and procurement. It also established the Office of Assistant Secretary of War for Air, a provision that did not sit well with the Army, which wanted to keep tighter control of the Air Corps. When the incumbent assistant secretary left office in 1932, no successor was named. The position was vacant until 1941.

When Gen. Charles P. Summerall departed as Chief of Staff in 1930, Airmen “may have hoped for more sympathy from General [Douglas] MacArthur, the new Chief of Staff, but they would not get it,” said historian James P. Tate. “MacArthur strongly concurred [with] the conservative views of his predecessor. For the next five years, he would fight for a balanced Army and vigorously oppose congressional proponents of air power.”

Congressional and public opinion tended to support air power, and the Air Corps was unrelenting in its effort to generate favorable attention by breaking and setting new records for altitude, speed, distance, and endurance.

Within the Army, though, the Air Corps was regarded emphatically as the junior branch and was expected to defer to the customs and traditions of the senior branches. Air Corps leaders, from Maj. Gen. Benjamin Foulois to Lt. Col. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, wore riding breeches as part of the Army service uniform.

“Early in the 1930s, the War Department had been willing to permit the development of long-range bombers, apparently because General MacArthur held a permissive attitude toward such an endeavor,” said Air University senior historian Robert Frank Futrell.

“The attitude of the War Department general staff switched abruptly after October 1935, when General [Malin] Craig became Army Chief of Staff. Beginning in 1936, General Craig and his deputy chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Stanley D. Embrick, pressed the entire army to reduce expenditures for research and development.”

In 1938, Embrick stated the general staff position that “the military superiority of a B-17, over two or three smaller planes that could be procured with the same funds, remains to be established.”

A similar view was held by Henry W. Woodring, Secretary of War from 1936 to 1940, whose background was in banking and politics. By Woodring’s order, the Army dropped plans for purchase in 1939 of 67 B-17s previously projected. In October 1938, Woodring decided that no four-engine bombers—only twin-engine B-18s—would be bought in 1939.

Woodring, an isolationist from Kansas, was at odds with Roosevelt’s policies, but FDR did not fire him because Woodring could deliver votes. The War Department’s position did not change until Stimson replaced Woodring in 1940.

Navy Discovers Air Power

The Army was careful not to reject bombers completely because the Navy was standing by, ready to take over the roles and budgets for air power should the Army abandon them. In 1927, the Navy proposed to acquire shore-based aircraft for “attacking enemy vessels over the sea by torpedoing and bombing.”

In so doing, ironically, the Navy was following in the footsteps of the despised Airman, Billy Mitchell, whose bombers sank a surplus battleship in 1921, contrary to Navy assurances that he could not do it.

The Army also wanted to retain the coastal defense mission and the funding that went with it. Traditionalists managed to ignore the inconvenient fact that in coastal defense, the Air Corps performed a mission in which air power was not tied directly to ground units.

The Air Corps reaped worldwide publicity with a promotional flight in May 1938 that embarrassed both the Army and Navy leadership. Three B-17s, flying from Mitchel Field in New York, found and “intercepted” the Italian cruise liner Rex, 725 miles out at sea. Passengers on the deck waved as the B-17s flew over, and the aircrews exchanged radio greetings with the Rex.

The Navy was not amused and complained to the Army. General Craig limited operations of Air Corps to within 100 miles of the US shoreline.

“As far as I know, that directive has never been rescinded,” Hap Arnold said in his memoir, “Global Mission,” published in 1949. “A literal-minded judge advocate might be able to find that every B-17, B-24, or B-29 that bombed Germany or Japan did so in violation of a standing order.”

Budgets and Shares

The Air Corps Act authorized a five-year program to expand the air arm to 16,650 members and 1,800 airplanes, but before it could be completed, the Great Depression curtailed federal spending. Owing to the procurement of aircraft that had already taken place and the transfer of more than 6,000 men from the other branches, however, the strength of the Air Corps in 1932 was 14,700 with 1,709 airplanes.

Budgets were meager for the next few years, but in “The Army and Its Air Corps” (1998), James P. Tate argues that the Air Corps fared better than others during these times.

In 1932, General MacArthur attracted considerable notice with a statement that aviation was the most expensive branch of the Army, and that between 25 and 35 percent of the Army budget was devoted to aviation.

Air power advocates have declared this preposterous, citing an Army historical report showing the Air Corps getting only 9.6 percent of the Army budget in 1932. MacArthur did not say where he got his percentages, which were almost certainly too high.

However, the Army report cited in rebuttal was based on a funding subtotal of “direct appropriations.” It did not count indirect Army appropriations—pay for personnel, equipment, medical services, food and supplies, and other things—which more than doubled the numbers. Inclusion of “equipment” would surely have affected the air power percentage.

A study in 1987 by the Office of Air Force History found that from 1920 to 1934, aviation accounted for between 13.1 and 22.7 percent of total military expenditures, with an average of 18.2 percent.

Air Corps budgets, personnel strength, and aircraft began climbing in 1936, and many of the older airplanes were replaced with newer ones. By the summer of 1939, the Air Corps had 22,387 people and 2,402 aircraft, although only about 800 of them were first-line bombers and fighters.

Bombers to the Forefront

The driving factor in the rise of the Air Corps in the 1930s was the bomber. With dramatic improvements in speed, range, and delivery of ordnance, it transcended local and tactical limits and became a weapon of strategic warfare.

The evolution was already apparent in the differences between the Martin B-10, which first flew in 1932, and the Keystone B-3A two years earlier. The B-10 was bigger and faster, of all-metal construction, a monoplane rather than a biplane. It had retractable landing gear and variable pitch propellers. Even so, developments in aeronautical technology soon promised more and better.

The Air Corps in 1933 requested design proposals for a new long-range bomber to succeed the B-10. The four-engine Boeing 299 Flying Fortress—which went on to become the classic B-17 of World War II—was expected to win the competition easily.

In the 1935 trials, the Boeing prototype crashed shortly after takeoff, not for any mechanical failure but because the pilot forgot to unlock the elevator and rudder controls. The winner was declared to be the two-engine Douglas DB-1, later the B-18 Bolo.

Following the competition, the War Department ordered the B-18. It had less range and payload than the Flying Fortress, but it cost only half as much. It was the standard bomber for most of the decade.

The Air Corps eventually got the B-17, the first 13 of them delivered in 1937, but not as many as it wanted and not as soon. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the Air Corps had 198 B-17s, with 93 more coming off the production line that month.

Fighters, still called “pursuits,” gained in capability, too, but not to the extent that bombers did, and they no longer dominated the structure of the air arm. The new bombers were almost as fast as the best pursuits. By the middle 1930s, bomber advocates—the disciples of Billy Mitchell—were in the ascendency in the Air Corps. The Air Corps Tactics School at Maxwell Field in Alabama was a hotbed of Mitchellism.

One of the few champions of pursuits was Claire L. Chennault, who later organized and commanded the Flying Tigers in China. He was never on good terms with his Air Corps colleagues, who thought the future belonged to the bomber. “Who is this damned fellow Chennault?” Hap Arnold asked.

The standard Air Corps fighter in 1939 was the Curtiss P-36 Hawk, forerunner of the P-36 Warhawk, which was coming on strong. A few of the open-cockpit P-26 Peashooters were still around in 1941. The United States had the best bomber in the world in the B-17, but it lagged other nations, including Germany, Japan, and Britain, in pursuits.

GHQ Air Force

Five months before Gen. Malin Craig became Chief of Staff and the clampdown on the Air Corps resumed, the Army made an amazing organizational concession to air power. General Headquarters (GHQ) Air Force was established, in March 1935, at Langley Field, Va.

GHQ Air Force took all of the air tactical units away from the individual Army field commands and put them under a single organization headed by an Airman. The concept of a general headquarters in the field to command a deployed force had been used by Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in the Civil War and by Gen. John J. Pershing in World War I.

War Department motives in 1935 are not entirely clear. In part, the Army hoped to head off recurring agitation for air power as a separate service. The change also provided an operational framework into which the growing capabilities of air power were a better fit.

For most of its existence, GHQ Air Force was led by the hard-charging Brig. Gen. Frank M. Andrews. Approximately 40 percent of the Air Corps strength was in GHQ Air Force. The chief of the Air Corps—Maj. Gen. Arnold from 1938 on—was responsible for training, schools, procurement, and supply. There was no single leader for the air arm.

Arnold was all for GHQ Air Force. “It was the nearest thing to an independent Air Force yet realized,” he said. It also set a powerful precedent from which the Army was unable to retreat. In June 1941, both GHQ Air Force and the Air Corps were incorporated into the new Army Air Forces, headed by Arnold.

FDR Sets the Course

Between the world wars, the leading politicians in both political parties were staunchly isolationist. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was ahead of the country and the Congress on the need to prepare for war, but he had to move more gradually than he liked.

FDR was a former assistant secretary of the Navy and notoriously partial to that service. At one juncture, General Marshall implored him to “stop speaking of the Army as ‘they’ and the Navy as ‘us’.” Even so, Roosevelt was the advocate of air power who mattered most.

At a White House meeting in November 1938, Roosevelt said he wanted an Army Air Force of 20,000 planes and annual production capacity of 24,000 planes, but recognized that Congress would not approve that many. He directed development of a program for 10,000 Air Corps planes, of which 2,500 would be training planes, 3,750 line combat, and 3,750 reserve combat. FDR said he did not want to talk about ground forces, that a new barracks in Wyoming would not scare Hitler one goddamned bit.

Marshall, who replaced Craig as Chief in September 1939, supported the B-17. When he was deputy chief in 1938, he made the case for the long-range bomber, using arguments similar to those long stated by Air Corps officers. Stimson, who became Secretary of War in July 1940, said, “It’s clear that air warfare involves independent action quite divorced from both the land and the sea.”

The National Defense Act passed by Congress in 1939 had authorized up to 6,000 airplanes for the Air Corps. In May 1940, Roosevelt called for 50,000 planes—36,500 for the Army and 13,500 for the Navy—and production of 50,000 airplanes a year.

By the summer of 1941, with the clock ticking down toward Pearl Harbor, the Army Air Forces possessed 6,777 aircraft, of which 120 were heavy bombers (B-17, B-24), 903 were light and medium bombers, and 477 were fighters. The B-17 was in significant production, and the P-51 prototype had made its first flight.

In 1942, the Army was divided into three autonomous commands: Army Air Forces, Army Ground Forces, (replacing GHQ Army), and Army Service Forces. During World War II, Arnold as Chief of the AAF was a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, alongside Marshall and Adm. Ernest J. King, the Chief of Naval Operations. Adm. William D. Leahy, FDR’s personal chief of staff, presided. The Chief of Army Ground Forces was not a member of the Joint Chiefs.