Each year hundreds of candidates are medically disqualified from military service. Is the Air Force off target in assessing future health?

Megan Brown was in her second year in the Air Force Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) at Clemson University when she learned in an email that her childhood shellfish allergy disqualified her from military service. Brown hadn’t had an allergic reaction to shellfish in seven years, but when she asked for a waiver, she was turned down.

Brown is among hundreds of seemingly fit, academically qualified, high-performing officer and enlisted applicants whose quests to serve in the Air Force are shot down each year by an opaque and confusing medical review process. Allergies, anxiety, ADHD, astigmatism in one or both eyes, and numerous other minor conditions can render otherwise qualified candidates unfit for duty in the Air Force—and, at the same time, often still able to serve other military branches.

Senior officers, military retirees, and even members of Congress field hundreds of complaints annually from applicants who feel wronged by what they see as a random and inconsistent system. In many cases, the same conditions that disqualify them as cadets would be waived were those conditions diagnosed after their induction into the military.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.)We want a screening process that catches disqualifying medical conditions, but … [is it] creating unnecessary barriers to enrollment?

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee’s personnel subcommittee, took up the issue at a Dec. 6 hearing. “One otherwise healthy applicant had to wait an extra two months to enlist while she proved that a childhood wrist sprain was not a disqualifying medical condition,” she told the heads of each military recruiting service. “Now, obviously we want a screening process that catches disqualifying medical conditions, but … [is it] creating unnecessary barriers to enrollment?”

Former Chief of Space Operations Gen. John W. “Jay” Raymond, now retired and the Chairman of the Board for the Arnold Air Society/Silver Wings (AAS/SW), thinks the review process imposes unnecessary barriers on young people who want to serve their country. AAS/SW is a national honor society made up largely of ROTC cadets.

“Our nation needs a well-trained, ready force, and there are medical standards that need to be upheld,” Raymond told Air & Space Forces Magazine. “I really believe, though, that we need a shift in [the medical review] culture. I think we are currently in a culture that starts out with a ‘no’ and tries to get to a ‘yes,’ rather than starting with yes and working hard to get the person in the service where it makes sense to do so.”

DIGGING INTO THE DATA

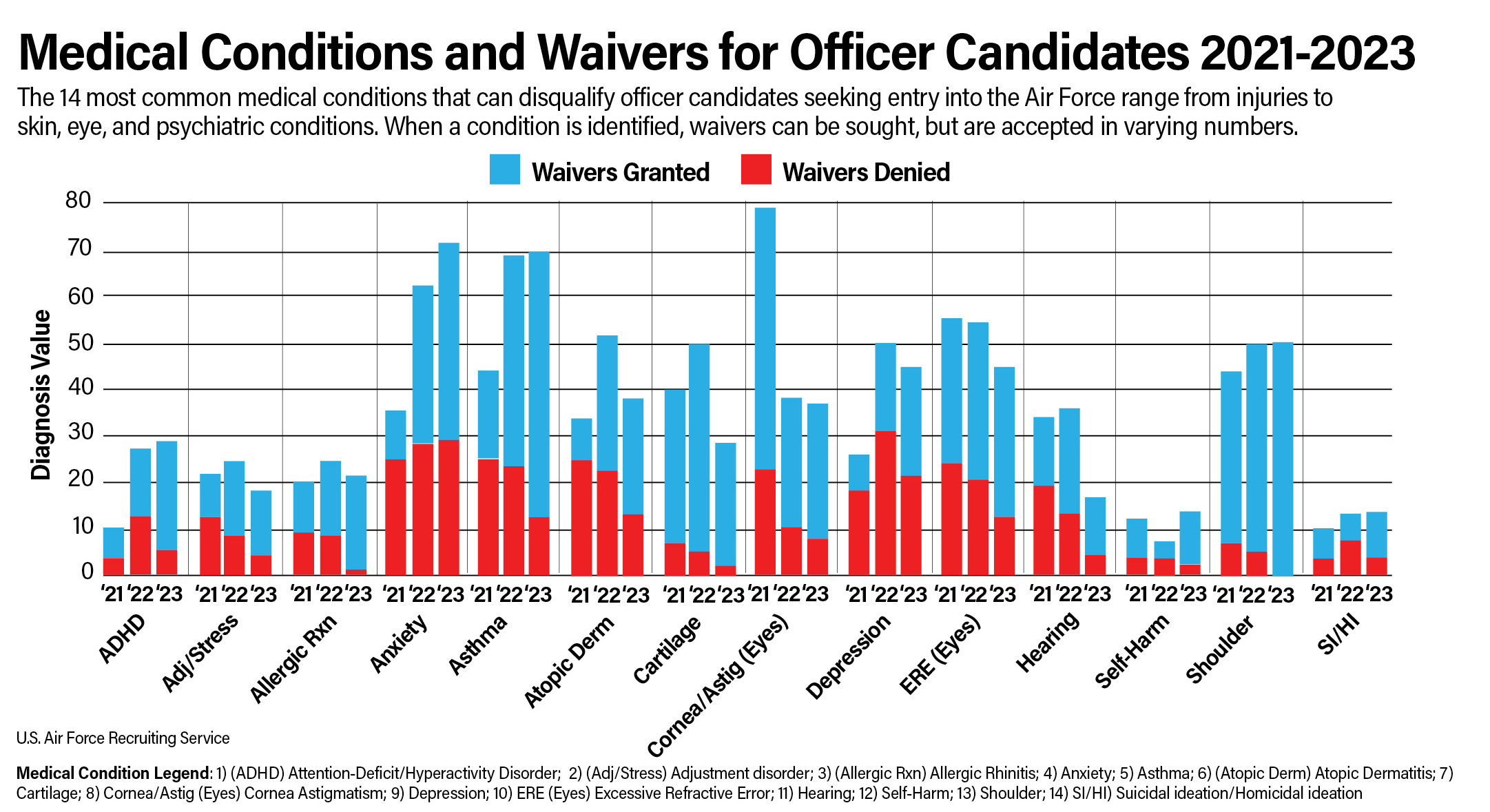

Waiver approvals for officer candidates increased steadily over the past three years, from 56 percent in fiscal 2021 to 64 percent in fiscal 2022, and 74 percent in fiscal 2023, according to data shared by the Air Force Recruiting Service (AFRS). That data lists the 14 most common categories for diagnoses and waivers each year. The likelihood of a waiver being approved varied by condition. For example, in 2021, only 26 percent of the applications for eczema waivers were successful, compared to 84 percent for shoulder conditions. A single candidate can apply for multiple waivers if multiple conditions are found.

The most common disqualifying conditions in this period included asthma, poor vision, depression, eczema, anxiety, shoulder and knee conditions, allergies, ADHD, poor hearing, adjustment and stress disorders, self-harm, and suicidal or harmful ideation.

Among all prospective enlisted applicants, the military services approved 77 percent of 54,206 medical waiver requests received from fiscal 2021 through 2022, according to a 2023 Department of Defense Inspector General report. But the approval rates varied by service branch: The Air Force was lowest at 65 percent, while the Marine Corps had the highest waiver approval rate at 98 percent. Because the figures combine two fiscal years, it’s difficult to see a direct correlation with officer candidate waivers shared by AFRS.

Still, waiver recipients do make up a substantial part of today’s Air Force and Space Force. Tech. Sgt. Jonathan Neff, who works at the Accessions Medical Waiver Division at AFRS Headquarters at Joint Base San Antonio-Randolph, Texas, said in a YouTube video published in September that 26 percent of all accessions in fiscal 2023 required a waiver. Most of those—some 20 percent of all accessions—needed medical waivers, while the other 6 percent required other matters waived, such as moral waivers for past criminal conduct, for example.

“We need these waivers more than ever,” Neff said. “We need to reduce these barriers to service everywhere we can. And our leaders are doing their absolute best to get after that.”

EXPLAINING THE PROCESS

Air Force enlisted applicants and officer candidates commissioning through Officer Training School go through their medical exams at Military Entrance Processing Stations (MEPS), while officer candidates commissioning through the U.S. Air Force Academy and ROTC are medically examined by the Department of Defense Medical Examination Review Board (DODMERB).

Academy hopefuls do not set foot on campus until they have been awarded a scholarship, for which they need to clear a medical exam, said senior flight surgeon Col. Ian Gregory, head of the Accession Medical Waiver Division at Joint Base San Antonio-Randolph, Texas. Likewise, most Air Force ROTC cadets were traditionally required to clear a medical exam before they could get scholarship funds, and most enjoyed four-year scholarships.

Nowadays, however, two- or three-year scholarships are more common, so a student may enroll in ROTC as a freshman or sophomore. Most ROTC cadets go to field training between their sophomore and junior years of school, Gregory said, and to do that they need to clear a medical exam. Cadets at the Academy and ROTC who are interested in flying must complete an additional physical their junior year.

By whatever means the medical exam occurs, however, if a disqualifying medical condition is identified, they must apply for a waiver to serve. And in the Department of the Air Force—whether the active Air Force, the Space Force, Air Force Reserve, or the Air National Guard—every waiver must be approved by Col. Gregory’s command, the Air Force Accession Medical Waiver Division.

The unit employs about 40 people, most of whom are enlisted or civilian medical technicians. The enlisted are noncommissioned officers trained as flight and operational medicine technicians and with work experience equivalent to at least a licensed practical nurse, Gregory said. Most of the civilians are GS-9s with prior military experience, Gregory said. They do not typically have expertise in the medical fields that routinely emerge in waiver decision requests, such as pulmonology, immunology, dermatology, and psychology.

The Accession Medical Waiver Division has five branches, three of which determine medical waivers. The largest branch evaluates enlisted medical waiver requests, the next largest evaluates officer medical waiver requests, while the third evaluates requests for aviation, special warfare, and other unique medical waiver requests. The fourth branch helps the other three with education and other support functions, while the fifth is made up of physicians who provide advanced technical expertise for the three production branches.

The division uses an internal document called the decision guide, which lists hundreds of medical conditions, the medical record information needed to make a determination regarding each one, and the criteria for disqualifying or accepting a candidate. The technicians use the guide and consult physicians on difficult cases.

RISK TOLERANCE

As part of the Air Force Recruiting Service, the Division shares the objective of meeting recruiting goals, Gregory said. “But we also want to bring in the right applicants, the ones who can do their job, which is to help the Air Force fight wars,” he added. “That sometimes involves going overseas and undergoing stress.”

Baseline medical standards for general accession are the same for officers and enlisted, regardless of service branch. The regulations are defined in Department of Defense Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1. But each military service can layer additional requirements on top of that baseline, establishing more stringent standards for specific career fields such as aviation and special operations.

The Air Force does not apply a more stringent blanket standard for Airmen, Gregory said: “We wouldn’t want to do that anyways, because that’s going to limit our applicants.”

But regulations allow each service to handle its own waivers, which can change over time, based on each service’s operational requirements and recruiting needs. In the Air Force, the guiding light for waiver decisions is whether an applicant can serve one deployment in a tour of duty—typically four years—without causing excessive stress to themselves or the mission, Gregory said. “We don’t expect someone to be perfect for a full 20 years.”

That means candidates must be able to withstand challenging climates, changing diet, stress, lack of hygiene, and harsh working conditions that may have unpredictable health effects.

“We look at the medical records that our applicants provide and compare it to the medical literature to say, ‘OK, within this condition, are they likely to have a recurrence of a problematic medical issue? And how does that compare to what will be expected of them while in the military?’” Gregory said. “It’s not as much the concern about office jobs versus physically demanding jobs, as it is the living environment and what that does to your condition.”

One example is food allergies, because avoiding allergens and treating exposures could be more difficult while deployed.

“In a deployed environment, you’re not able to control exactly what you eat,” the colonel said in a 2023 YouTube interview with AFRS. In very hot environments like the Middle East, epinephrine pens tend not to work as well, he added, and even if they do work, the service member would still need to be taken immediately to an emergency room, “which are not always easy to access.”

“We have to explain to people that just because they have a well-controlled condition in the civilian setting doesn’t mean that it’s appropriate for the military environment,” he told Air & Space Forces Magazine.

Waiver calculations are relatively straightforward for candidates heading off to Basic Military Training or Officer Training School. For ROTC and Academy cadets, however, Gregory’s office must project their health further into the future, because they won’t finish college for three or more years. And because the Air Force tends to meet its officer accession goals, medical reviewers apply a lower risk tolerance when reviewing officer candidates.

This variable is generally not well understood. The Air Force adjusts its risk calculus based on supply and demand; as the Air Force has struggled to find enough recruits in recent years, its risk tolerance—that is, its willingness to issue a waiver—has increased.

“We’re looking to kind of open up the aperture a little bit more compared to previously,” Gregory said, referring to the current outlook. “But the pendulum doesn’t really swing back and forth, at least it hasn’t,” he noted. “Doesn’t mean that it couldn’t, but it just hasn’t really because historically that has not been the need.”

The Air Force’s risk tolerance rises for members who develop or discover health conditions after joining the service. The logic is that the Air Force has already invested in training them, and that more experienced Airmen who develop conditions have already proven they can do their jobs. There are different medical standards for accession and retention, Gregory explained.

“If someone develops a condition, we have some time to say, ‘Yes, we think it’s worth it to retain this person because they have shown that they can do what we need them to do in the Air Force,’” he said. “Whereas if someone has not been trained, they’ve never been in the Air Force, the risk and value equation changes such that the risk seems to outweigh the value.”

At least, that’s the way the process works on paper.

‘THE AIRFORCE IS MISSING OUT’

Rejected cadets tell a different story.

Levin Brandt was at the top of his cadet class, commander of the Honor Guard, and earning excellent physical fitness scores at the University of North Dakota’s ROTC program when, in his second semester, he was disqualified for hay allergy-induced asthma.

“I was beyond frustrated,” Brandt said. “Unless in a hay loft, I am completely unaffected. I don’t believe the military has a hay loft and if they did, I could easily work in a department without a hay loft.”

Brandt applied—unsuccessfully—for a waiver. He acknowledged that his medical “resume” is very long—but noted that asthma was the only disqualifying condition. The Marine Corps turned him down for the same reason.

“It’s crazy that a blanket policy about asthma was what got me,” he said. “That it’s not even waivable and there are no subsections with more specifics as to the certain types or severities of asthma that they are trying to avoid.”

Brandt nevertheless got involved in the Silver Wings Society, a national organization that promotes civic leadership through community service and education about aerospace power.

“Medically disqualified [cadets] make up a good portion of the Silver Wings leadership, meaning that the Air Force is missing out on a lot of great leaders,” said Brandt, who served as the society’s national president for a year.

Indeed, among 13 former AFROTC cadets who shared their medical disqualification stories with Air & Space Forces Magazine, several were active in Silver Wings. All shared a strong desire to serve in the Air Force but were medically disqualified.

“I want to serve our country, in uniform, in any capacity the Air Force sees appropriate,” said Brandon Weide, another former cadet. “I stand ready to serve at least a full 20 years.”

Weide was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, an inflammatory bowel condition, when he was 12. Though he achieved remission two years later, at 14, he continues to take medication to manage the condition. He already has an FAA Commercial Pilot Certificate, the highest-possible medical clearance from the FAA, and consistently achieves excellent physical fitness scores.

“None of these factors, including extensive exposure to aeronautical operations and physically demanding military training, has worsened my Crohn’s disease or generated any negative symptoms,” he said.

Attempts to gain a waiver and multiple congressional inquiries proved fruitless. Nor would the Air Force offer any additional insight into their decision process.

“The clearest answer given was that I did not meet the ‘level of exceptionality’ reserved for issuance of an exception to policy,” he said. “When I asked for more information via additional congressional inquiries, conditions required to meet the ‘level of exceptionality’ could not be accurately defined.”

Yet Crohn’s and other bowel diseases are not disqualifying for members already serving, even in flying billets. In 2021, Air Force Lt. Col. Josh Nelson returned to flying C-130s after having his colon surgically removed due to ulcerative colitis. In 2023, Capt. Charles Boynton was declared fully mission-capable in the F-16, despite a diagnosis of testicular cancer five years earlier. In 2020, Col. Todd Hofford became the first pilot to fly the F-15 after undergoing cervical disc replacement surgery four years prior.

All three spent years battling the Air Force medical bureaucracy to regain their qualifications, but eventually succeeded. That makes cases like Weide’s even more confusing.

“I was essentially told there was no AFSC [Air Force Specialty Code] or position, rated or non-rated, which I could hold in a uniformed capacity because of my medical condition, and I was being told this while officers continued to fly in the operational Air Force with Crohn’s disease, even after multiple surgeries,” he said.

Other cases are even more perplexing. Justin Tasca hesitated while filling out his DODMERB paperwork, hovering over the question “Do you have Dyslexia?”

Tasca was an A student and had made the dean’s list at Northern Arizona University multiple times. While he read a little slower than others, he had essentially overcome a childhood diagnosis. But rather than lie, he checked “yes,” and was medically disqualified.

“Becoming a pilot, navigator, or special forces might be out of the question,” Tasca acknowledges. “But why couldn’t someone [with dyslexia] serve as an aircraft maintenance, logistics, acquisitions, services, or security forces officer?”

Hadn’t he already proven that he could excel despite the condition?

In other cases, candidates found themselves confounded by the seemingly different standards between the military services or between officer and enlisted accessions. One Air Force ROTC cadet told Air & Space Forces Magazine that she was disqualified from AFROTC for a hip tear suffered in a car accident—but told she could enlist or apply to Officer Training School after getting treatment.

Another ROTC cadet said the Air Force classified a childhood upper respiratory infection as “mild asthma,” even though she had never been diagnosed with asthma. She went to see a civilian specialist, who explicitly stated that she did not have asthma. But the Air Force refused to waive the matter.

The cadet later joined Army ROTC.

Megan Brown, the Clemson University AFROTC cadet disqualified because of a shellfish allergy, said the waiver process kept her hanging, giving her false hope.

“If the DODMERB office will not waive an allergy no matter what, then I think they should tell cadets that so that they do not go through the waiver process,” she said. “I had to pay for the appointments out of pocket for them to mean nothing. I think that the policy could provide more set rules or answers for cadets to look at, as the DODMERB process is very extensive, and can be very confusing.”

‘IT’LL NEVER BE PERFECT’

As executive director of Silver Wings and its partner organization, Arnold Air Society, retired Brig. Gen. Dan Woodward hears many such stories from highly motivated cadets.

“For more than a decade, I’ve been fortunate to work with some of the most outstanding students in AFROTC,” he said. “They are patriots who want to serve their country. Some have exceptional academic credentials, are otherwise physically qualified, and have the highest recommendations from their ROTC detachment commander.”

Yet many are disqualified for conditions that have not affected them for years, he said, “or which would have been waived were they six months downstream having raised their right hands. It’s really difficult to see them having problems with deployments or anything else once they wind up in the Air Force.”

And while ROTC cadets are supposed to be medically cleared before receiving scholarships, Woodward said it “absolutely” happens where cadets receive scholarships but are later disqualified anyway, sometimes just months away from commissioning.

“We’re bouncing some really stellar people out of the United States Air Force and Space Force for reasons that seem really, really questionable,” he said.

Woodward called for a comprehensive look at the medical standards, with a particularly close eye toward conditions that would be waived for Active-duty Airmen.

“When was the last time we’ve really taken a look at this?” he asked. “Because the circumstances have changed over time.”

Particularly dismaying is when cadets are disqualified from one service ROTC program, then end up joining another. Woodward, who served 29 years in the Air Force, was disqualified from the Army due to flat feet. He agrees he may not have been cut out for marching tens of miles with a 100-pound pack, but his condition never affected anything he did in the Air Force.

Similarly, Woodward said he’s seen anecdotal evidence that military children can be disadvantaged in a system where their medical histories are more accessible to military evaluators.

“When do these conditions become moot?” Woodward asked. “I find it really frustrating when a cadet is disqualified for something they have not had since they were 12.”

The review process will never be perfect, “because it’s run by people,” he added. “But we really should take a look at this, because we’re bouncing great people.”

‘MORE TO THE STORY’

Why are so many candidates being disqualified for seemingly no good reason? Gregory insisted there is more to the story.

“You’ll hear a part of the story, I’ll have a part of the story. And then the truth is somewhere in between,” he added. “Occasionally when we get these complaints through various mechanisms, we will change our mind because we miss something, or there is new information. But most of the time, we’re considering something else that the applicant either doesn’t know, or the applicant isn’t aware of our perspective.”

When the Accessions Medical Waiver Division provides a disqualification “we have to match up the reason they were disqualified to whatever MEPS or DODMERB disqualified them for,” he said.

For example, if MEPS disqualified an applicant for asthma because they used an inhaler, the waiver division may request further testing which finds the applicant does not have asthma, but they may have another lung condition that disqualifies them.

“In the response they get disqualified for that same reason they were disqualified in the first place,” Gregory said. “But really, our logic is, well, they have some other kind of lung condition.”

Because the waiver division chooses to limit how much of its homework it shares, such as the exact standards for passing a lung function test, the disqualified applicant is left in the dark.

“I don’t want to give someone the answers to the test so that they can just provide the answer that they think I want to hear,” Gregory explained. “They need to provide the answer that is true for them.”

The concern is more pertinent for subjective conditions, such as how much pain an applicant feels from chronic headaches, since there is no way to validate someone’s pain, Gregory said. If an applicant knows they can get a waiver if they require prescription pain medication for headaches just twice a year, for example, then “they’re going to say exactly what we want to hear, whether or not that’s their real situation.”

If allowed into the service, “and then they start having their headaches again, and then they need more care, then that can affect their ability to do their job,” he explained.

Still, Gregory said there is room for improvement in how a rejection is communicated to applicants. Delivering the bad news falls to recruiters and ROTC detachment commanders. The ideal message would be sensitive to the pain an applicant experiences. “We will always come up short, because someone wants a certain answer, and in these cases we’re denying it,” Gregory said. “That hurts, that’s hard, and I’m sympathetic to that. Therefore it’s not just what the message is, but how it’s delivered, and that’s just communication.”

ACCOUNTABILITY

Each month, the chief of each branch in the Accession Medical Waiver Division reviews about 10 random cases from each technician to ensure their decision-making is sound. The division also reviews its decision guide “continuously,” Gregory said. There is no formal external audit, however. “We get picked all the time by various congressional complaints or general officers or retired family members,” he explained.

“We get all the time people saying, ‘Hey how come this person got DQ’d? Can you look at it again?’” he said. “And so we go back and look at things again. And that happens multiple times a week.”

Rarely, a second look results in a different decision from the waiver division, but most of the time, the division stands by its initial choice. The colonel said he would not be opposed to an audit, because “I’d feel confident that in general we do good work.” But if anything affects the accuracy of their decisions, it’s the pace of work, he said.

“I know that maybe if we don’t do things 100 percent accurately, part of that is because we’ve been asked to do things quickly, and certainly anytime there is an increase in pace, there’s a risk of doing things less precisely,” he explained.

The ramped-up pace is due to the Air Force’s recent recruiting challenges. After taking the helm of AFRS in 2023, Brig. Gen. Christopher Amrhein identified long medical processing times as a barrier to service. In fact, Senator Warren grilled him and the other top military recruiters about it in the December hearing. AFRS hired about 60 contractors to work in and around MEPS locations to help with medical paperwork, buying two or three hours a week back for each recruiter.

When a waiver request arrives at Accessions Medical Waiver Division, it usually takes about three days for a technician to get to it, Gregory said. In the past, insufficient staffing has stretched the backlog as far as three weeks. Once a technician gets to the waiver, they usually decide either to close it or ask for more information that same day.

The division does not track the total time it takes to close a case, “because plenty of times we send a waiver back to ask for more information, and then it could take days or weeks to get that information,” he explained. “It’s out of our hands.”

The goal is to minimize how many times that happens, so the division is refining its processes to make sure MEPS and DODMERB send in all the relevant records the first time around.

FUTURE CHANGES

The military’s medical standards are not set in stone. Gregory is part of the Accession and Retention Medical Standards Working Group, where he and experts from other services meet every month to see if any standards need to be updated. For example, regulations were recently changed to reduce the number of applicants disqualified for having a history of gastrointestinal bleeding, or for conditions where their eyes do not track and focus together.

The Air Force has also gradually refined its waiver tolerances. Eczema used to be a medical disqualifier, but in 2017 the service began issuing waivers for the condition. ADHD medications still are not allowed in the Air Force, but in 2017, the service reduced from 24 months to 15 months the amount of time applicants must have been off those medications before they can be considered.

Another recent change: Body fat composition standards were loosened last year, raised from 20 percent to 26 percent for men and from 28 percent to 36 percent for women. The change made it possible for nearly 700 applicants to become Airmen in 2023 alone.

Diabetes used to be an automatic disqualifier, but even that is changing now. In 2021, the Space Force commissioned Air Force Academy wrestler Tanner Johnson as a second lieutenant, recognizing that his Type 1 diabetes need not disqualify him from serving because the Space Force fights from its home bases, rather than deploying to isolated bases overseas. How the services evaluate candidates is ripe for review. Gregory acknowledged the open secret that some MEPS locations are easier than others.

“There are 65 different MEPS out there, so inherently, you’re going to have some variability in the processes, the population, the staffing,” he said.

U.S. Military Entrance Processing Command, which oversees MEPS, wants to boost staffing levels at some stations, which should shorten the timelines for evaluations and processing there, the colonel added. Six stations are also trying out a new search tool within the health information exchange which should make the process of finding disqualifying conditions in someone’s medical records faster and more accurate.

In the meantime, Gregory wants better data to inform his team’s waiver determinations. The Air Force does not specifically track how waiver recipients perform over the course of their careers. Did they deploy successfully? Did problems emerge? Did the member fulfill their service obligation? And how much medical attention did they need while in uniform?

“What I want to know is ‘are my decisions accurate?’” he said. “We have some superficial data, but we don’t have the kind of granular data that we need to know, with precision, that our decisions are correct.”

Gregory estimates the analysis would cost several million dollars a year.

“When you use data from the past, you evaluate it and you say, ‘Aha, I can probably make a different decision moving forward,’” the colonel explained. “Maybe that decision is to open up the waiver tolerance or maybe it’s to close it. That’s what we want to know.”

Raymond’s Recipe for Fixing Waivers: Change the Culture

Anecdotal evidence and the personal experience of military leaders suggest that much can be done to improve the medical review process. Gen. John “Jay” W. Raymond, the first Chief of Space Operations, recommended six steps to help healthy, qualified candidates serve their country without letting medical evaluations become too restrictive:

Change the culture. Shift the approach to where “it is okay that we are working with folks to get them qualified rather than just defaulting to no.”

Clarify standards. Use up-to-date medical evidence to ensure disqualifications are not based on outdated science.

Apply standards consistently. Ensure standards are uniform across the officer and enlisted spectrum, so that an applicant cannot be denied a commission but still be able to enlist.

Use like standards for like jobs. The requirements for flying fighter jets in the Air Force should be the same as those for flying fighter jets in the Navy and Marine Corps, for example.

Ensure consistency across Military Entrance Processing Stations. “I have heard relatively frequently that not all MEPS are created equal when it comes to getting approved.” The standards should be the same no matter the region and no matter the applicant.

Communicate standards clearly. Applicants should not be caught off-guard.

Raymond cited his decision to help two people with Type 1 diabetes into the Space Force, a military first.

“Diabetes can be well-monitored and controlled,” he said. “Allowing folks to serve if their jobs allow them to serve in areas where they can access proper medical care, as is the case in the Space Force,” he said. Most Guardians serve near robust medical centers. “I’m not saying that’s the right answer for everybody, but it should not be a disqualifier for everybody right off the bat.”

Other conditions that deserve further review and consideration include eczema, childhood asthma, and even some mental health conditions, the former CSO said.

“I think we need to be a little bit more open to individuals who in the past have sought counseling to manage stress,” Raymond said. “On the one hand, we are encouraging those currently in the service to seek help, while on the other hand, we are making it difficult for those that have done so prior to coming on Active Duty to serve.”

Raymond said the Office of the Secretary of Defense should initiate changes and ensure consistency among the services, but that each military branch should step up its own efforts to communicate standards more clearly.

“I don’t think it will be easy, but I think it’s necessary,” he said. “It will take some out-of-the-box thinking and a willingness to change the culture.”