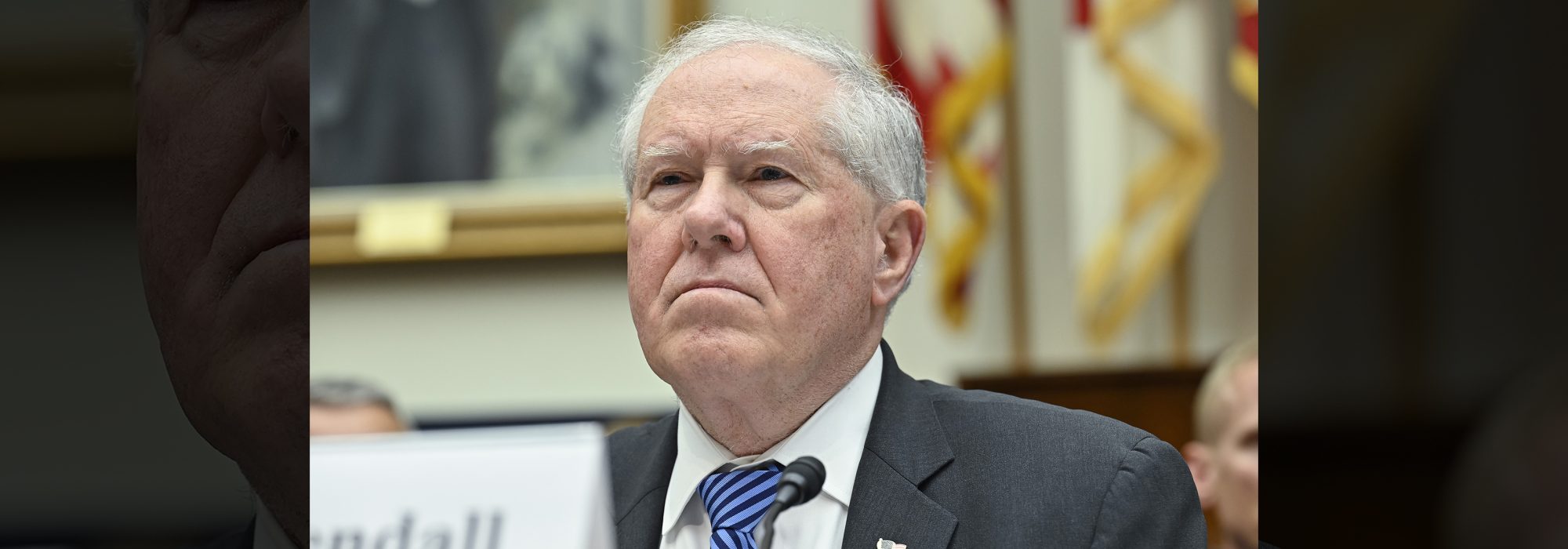

From the moment he returned to the Pentagon as the 26th Secretary of the Air Force, Frank Kendall III was applying his Cold War experience to the challenges of modernizing the Air Force and Space Force and accelerating changes and enhancing operational effectiveness. China had replaced the Soviet Union as the pacing threat, but the art of countering a sophisticated adversary was the same. Kendall has held senior defense civilian jobs in the Pentagon since 1986, even before Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman graduated high school and the same year Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David Allvin earned his commission. Now 75, Kendall’s focus on China has only grown more urgent. He met with Air & Space Forces Magazine’s Pentagon Editor, Chris Gordon, and Editor in Chief, Tobias Naegele, in January. This interview has been edited for length and, in rare cases, clarity.

Q: You’ve had a pretty momentous run as Secretary, your focus on seven Operational Imperatives (OIs) has won wide acclaim. Now you are driving toward a major “re-optimization” of the Department of the Air Force. Why risk distracting from that success to try do so much, so fast?

A: The OIs were about modernization. When I walked into the job, I knew from my AT&L experience and my time in industry, that we needed to move forward with modernization pretty aggressively—that China was trying to field systems designed to defeat us, and we had to get to our next generation of capabilities. So we put a lot of effort into that, and we still are. We’re still waiting for the ’24 budget to pass, which is where a lot of the funding for the OIs is initiated. But over that period of time, working particularly with the service Chiefs, we’ve come to the realization that there were a number of other things besides modernization that we needed to address.

I go back to having had 20 years of Cold War experience. I was here [at the Pentagon] for the Obama administration, where we did operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, and we did the ISIS fight, and so on. And we didn’t have any trouble executing the kinds of operations we had to do for those contingencies. So I had an assumption, walking in the door: That the Air Force and Space Force, despite its newness, were basically structured and ready for whatever conflict might happen. And the realization has come to me over the time that I’ve been here—and the Chiefs are 100 percent in agreement with this—that we’re not as ready as we should be, for great power conflict today.

And the reason for that is that over the 30 odd years, since the Cold War ended, we have drifted away from preparing and assessing the readiness of the force or structuring the force or managing the force, so that it is truly ready for a short-notice great power conflict. And as you dig into that, and you start to investigate—how are we really structured and, postured today?—You discover more ways in which we are really not optimized for great power competition.

Let me give you a few examples. We’ve been supporting rotational deployments to the Middle East for decades now, and I just visited five of those bases. The way we’ve gravitated to do that is not to send fully operational deployable units to those bases, [but] … send fighter squadrons, or some operational flying units, coupled with a large number of support organizations, which are crowdsourced. We basically asked people throughout the Air Force, OK, we’re doing a rotation, we need some people of this type, who wants to go? … Those are not fully trained ready operational units we’re deploying. But if we’re called upon to support an operation plan in the Pacific or in Europe, say, against a great power, we need ready deployable units, that can go do that job. And that’s not what we have right now. … The units themselves have got to be structured to have all the capabilities they need when they go, and you want to have unity of command for those units. We don’t have that right now. You know, basically, when a new commander gets over there, his team does show up that day, and they just start to do what they’re doing. And we’ve gotten used to that. It was an efficient way to do the kinds of things we’ve been doing for the last 20-odd years. But it’s not the way you want to go into a great power conflict. And that goes across the Guard and Reserve elements of the force, as well. …

The work that we did to create the Operational Imperatives, I came to the realization that we did not have organizations in place that were spending their time maintaining competitive advantage. So we want the units that are responsible for readiness to be responsible for readiness, and to be focused on that. And to be ready to go fight on a short notice, right? But we also need units, we need organizations that are focused on sustaining competitive advantage over time, from both the operational perspective and from the technical perspective of acquiring those capabilities and maturing technologies. And we found that we really didn’t have either.

On the technical side, what we have is a number of program executive officers (PEOs) with buckets of programs they are trying to deliver. And they are focused entirely on delivering those buckets of programs. And then you had an [Science and Technology] organization, at AFRL, which was focused on advancing technology. In both cases, we did not have integrating organizations whose job it was to think about how we stay competitive over time, and to do the combined operational planning, and the technical planning, the maturation of technologies in a pipeline of continuously improving capability, which is what you need against a competitor who’s actively trying to field the ability to defeat you all the time and continues to modernize. … Here in the headquarters, I had to bring in Tim Grayson and create an organization that was essentially a chief engineer of the Department of the Air Force. I didn’t have that. So he has become the integrated capabilities chief technical person for me. I had to create [Gen.] Luke Cropsey’s integrated PEO organization; I didn’t have a C-3 systems command to go with a task commander to go task to do what Luke is doing. So we’ve had to do ad hoc things to complete tasks that should have had someone in place with that as their mission.

The nuclear side of the enterprise has become if anything more important, and more critical, given Chinese expansion of their nuclear force. So Global Strike Command is fine in terms of the operational side of that. We have the nuclear weapons center at the two-star level under [Gen.] Duke Richardson and we want to broaden that. We’re looking at making sure we have a senior leader who is in charge of everything that supports the nuclear warfighting part of the force, both in space and the air. … Electronic warfare is another area in which we need to be competitive continuously. … The cybersecurity operational force, we have the cyber forces at 16th Air Force under ACC, that’s critical, and that should be supporting the entire Department of the Air Force, not just the Air Force, but also the Space Force. So we have to look at is that in the right position, both on the operational side from the point of view of operational capability, and on the technical side, from the point of view of maturing, and staying competitive in that area. So we basically found a number of areas in which we had moved away from a focus on staying ahead of a an aggressive competitor, to being efficient. We went through 10 years of sequestration, of being efficient at doing the things we were currently being called upon—you know, the current rotational deployments, respond to individual regional crises like Ukraine and Gaza, but not postured or oriented on being currently ahead of and staying ahead of a peer competitor. So that’s what we’re trying to address.

Q: You talked a lot about structure just now. So is this re-optimization or is it a reorganization?

A: It’s about more than organizational structure. It’s also about how we train people. … What kind of skill sets we want to have, what that mix of skill sets is. We’re looking at how we fight. What are the units that we actually use, and how they’re structured, particularly the units that are in CONUS, that are going to be called upon to go forward and fight with short notice. Those units already in theater, they have a combat mission, they’re structured to do that mission, and they practice it—but one of the key things we’re trying to do against peer competitors is Agile Combat Employment (ACE). We haven’t actually done everything we need to structure the force to be able to use it effectively.

And we haven’t been evaluating ourselves—how we assess and evaluate readiness and how we create readiness. You know, when the last time was we actually went to a unit and said, ‘The war has started, show me you can go?’ Decades—it’s been decades since we did that. We should be doing that all the time.

Q. What happens if you leave at the end of this year?

A: I don’t know if I’ll leave in a year or not, but that doesn’t affect this. The two service Chiefs are leading this, if not as much as I am, more than I am. They’re fully on board. [Gen.] Dave Allvin and [Gen.] Chance Saltzman are both very enthusiastic about this. And whatever happens to me, they’re going to continue with it. They’re going to have prominent leadership roles ensuring that it has success. Allvin put out his initial letter to the force, talking about following up. That’s what he’s talking about. We’re going to take “Accelerate Change or Lose,” we’re going to finish defining what the changes are that we need, and then we’re going to execute them.

Q: You mentioned coming back from the Middle East and those forces built as part of the first AFFORGEN forces. What did you see and how can USAF improve?

A: We’re experimenting with something called Air Task Forces right now, where we’re forming the units that would be deployed several months before they go. So we’re identifying them now, as opposed to [issuing orders and assembling the team in theater.] … We’re going to put those units together ahead of time, give them six months—at least—to prepare themselves for the deployment, so when they show up in theater, they’re ready to function as a unit. This is for the specific rotational deployments we’re doing now. [But] those are not the same forces we need in a contingency for a major combat operations against a peer competitor. … What we need when we send units forward to let’s say, Japan, or Guam, or to somewhere in Europe, are units that are ready to fight in that [specific] environment when they get there.

Q: So are Airmen and units going to be assigned to specific regions?

A: We have to go do all the detailed planning for this once we sort out exactly what those units look like. Then we have to go through the detailed planning. But, generally speaking, units in the AFFORGEN cycle will know, if there is a conflict, that it will be to a certain theater. We would like them to know what bases they’re going to be operating from so that they’re ready to go in and do ACE for the collection of bases where they would have to do it, how they would fall into the theater, so they can be prepared to fight as soon as they arrive.

Q: You mentioned ACC, AFGSC, AMC, you didn’t mention PACAF and USAFE. They are structured differently, operate differently. How will this affect them?

A: They’ll be the beneficiaries of this. We will work with the combatant commanders and component commanders for the Air Force, both, for any changes we need to make in theater to make sure that they’re comfortable, and we will also work with them on what we’re going to do in CONUS, to support them more effectively than we do now. So they’re all going to be involved in this. I mean, in the case of Air Mobility Command, assets are already part of TRANSCOM for the most part. In the case of Global Strike, they’re already part of STRATCOM. ACC is a little different, in that most of Air Combat Command’s units would be deployed somewhere else to fight, into one of the theaters. So I think the greatest impact will be there.

Q: And that’ll be additive?

A: I think it’ll be more about restructuring. If you go to an air base today, and you’ve got a wing commander, and you’ve got a base commander, a base wing, a lot of the assets that are actually under the base would need to go with the unit if it deployed to fight. So we want to adjust that so that those units are already associated with the unit that will go actually into combat.

Q: What about the Space Force. How does this affect that service?

A: Space Force generally, fights deployed in place. But they’re supported by Air Force units that operate the bases that they’re on. So we have to sort out what happens to all of those assets if they’re mobilized, and the base has to operate in conflict. You know, are there issues there with sensing the resiliency on the base, and how we ensure the resilience of the base, as well as whether we ensure that the appropriate forces are there to provide physical security and other things the base needs to function against the threat.

Q: Does that change who owns those forces?

A: I don’t think so. The Space Force has been focused on what it needs for operational reasons. With support largely coming from the Air Force, I don’t think we’re going to change that.

Q: AMC supports TRANSCOM, Global Strike supports STRATCOM. These organizations advocate for their own resources. They want their own stuff. But as you mentioned, this is a lot about reoptimizing to get everyone on one page?

A: I’m glad you asked that. Yeah, we have to have people who are thinking about integrated capability, and integrating capability, planning, modernization, and readiness. And so we need that on the operational side. And on the technical side, as well. So we’re going to create some structures designed to have that mission. You can make an analogy to the Army Futures Command. We’re not going to do that exactly, but we’re going to do something that has some of the same roles.

Q: The Air Force had a Systems Command until 1992, which was combined with Logistics Command to create Air Force Materiel Command. Is that coming back?

A: There were also systems commands that were, for example, C-3. So we’re not looking at things that have some connectivity to that or some functional resemblance to what we had before. We’re trying to tailor it to what we need now. We’ve got to be modernizing quickly and competitively, which means we need to have a constant pipeline of new capabilities coming in out of the S&T base as efficiently as possible. We’ve got to have sound operational concepts that evolve as technologies change and opportunities arise to be more effective. We’ve also got to have the capability to deploy forces on short notice to deal with a major conflict somewhere. There are a lot of pieces of the puzzle.

Q: You’ve mentioned a lot of things where you could improve, but presumably, you’re not going to be able to do everything you want. What’s actually doable?

A: Well, we’re resource limited, right? So the intent to not have a huge cost impact. I don’t think the cost impact is going to be zero. [But] some things are very simple—staff relationship changes, for example. I mentioned Tim Grayson, chief engineer. We’re looking at some capability focused on competitiveness across the department in the Secretariat, which is relatively minor organizational change. We’re looking at some changes in how we train people. We’ve used the idea of multicapable Airmen for a long time, right? We’ve sort of encouraged people to learn more than one skill, and we’ve given them opportunities to do that.

What we’re talking about now is something called Mission Capable Airmen. It’s not going to be optional. It’s going to be a requirement in certain roles, in certain commands, that when you go out to an ACE remote spoke or hub, that you’ll be able to do more than one job when you get there. And it’s not going to be an option for people. It’s something we’re going to tell them that they have to learn how to do.

We are looking at this because we’re in a technological competition, we have to be good both operationally and technically. We’re looking at career paths for people that are focused on technical expertise, and sustaining that over time. So we’re looking at things like technical tracks for officers and NCOs, and possibly creating something like a warrant officer track for people that are in technical fields like cyber, for example, where a lot of people don’t want to do other than technical things, who would stay in a technical role and build up expertise over a career as a technical expert.

Q: And electronic warfare? Your top EW is a colonel. Even General Cropsey is a one-star.

A: One of the things we’re working on is how we’re going to elevate some of the things that are really important for a peer competitor, which have not been important against the kind of adversaries we have had in the past, and to make those more accessible across the breadth of the service and the COCOMs.

We’ve been working on this since about September, and it’s been a sprint. I put a letter out to the force then saying we’re going to do this. And we’ve had five lines of effort. And those teams have been working with a lot of very intense supervision by myself and the two service Chiefs and the undersecretary for the past few months.

Q: So why September? Why the rush now?

A: There was a period of learning for me of, you know, an understanding from interactions with people throughout the department about our current status and what we have, and also just some observations as I was doing the OIs and other things, and then a consensus among the senior leaders, the four senior leaders that, you know, we needed to move forward. And that, we could see the general direction in which we needed to go and what we needed to address. We’re not in a period where we’d have the luxury of being complacent or taking our time. If we went at the normal Pentagon pace for these things, we’d be staffing things for two years.

We don’t have two years. So we set up a four-month sprint roughly, we’re going to make the key decisions and we’re going to move forward. And if we find out as we execute that some things aren’t exactly what we optimized, we’ll make adjustments as we go. We don’t have any time to waste. I was at [Gen.] Steve Whiting’s change of command and promotion yesterday. He’s taking over Space Command. Xi Jinping has told his military be ready to invade Taiwan by 2027. [Gen.] Steve Whiting will still be in command of the Space Command in 2027. I think we should get going. He agrees.

Q: What if the threat changes?

A: The threat is changing, and it will keep changing. China is a thinking, well-resourced adversary. They’re now thinking about the things we’ve said we’re going to do and how they’re going to defeat them. That’s why we have to re-optimize. We’re in a race. And we can’t just hope we win. We have to actually do things to make sure we stay ahead.

Q: Some past reorganizations went well. Others not so well. Change is hard. How do you get buy-in?

A: Change is hard, losing is unacceptable, right? We don’t have a choice about this if we want to win.

The two service chiefs we have I think are the right people to do this. We talk every day. You’ll hear from Dave Allvin and you’ll hear from Salty about their intentions with this. And I think you’ll find that reassuring. I do. We’re not making any decisions or doing anything in this exercise that doesn’t have the complete and total support of the service chiefs.

Q: How about the other four-stars?

A: They’ve been consulted as we’ve gone all through this, and I think that they’ll be on board as well. I think there’s a widespread recognition that we need to do this sort of thing. There may be different opinions about some of the details, but the fact that we need to reorient ourselves toward the pacing challenge? I don’t think anybody disagrees with that.