USAF bet billions on Adaptive Engines. Are they ready now?

After nearly 15 years in development and a $4 billion Air Force investment, two brand-new fighter engines are in test, promising game-changing improvement in range and thrust. Which airplane they will equip first—and when—is suddenly a hot debate in Washington.

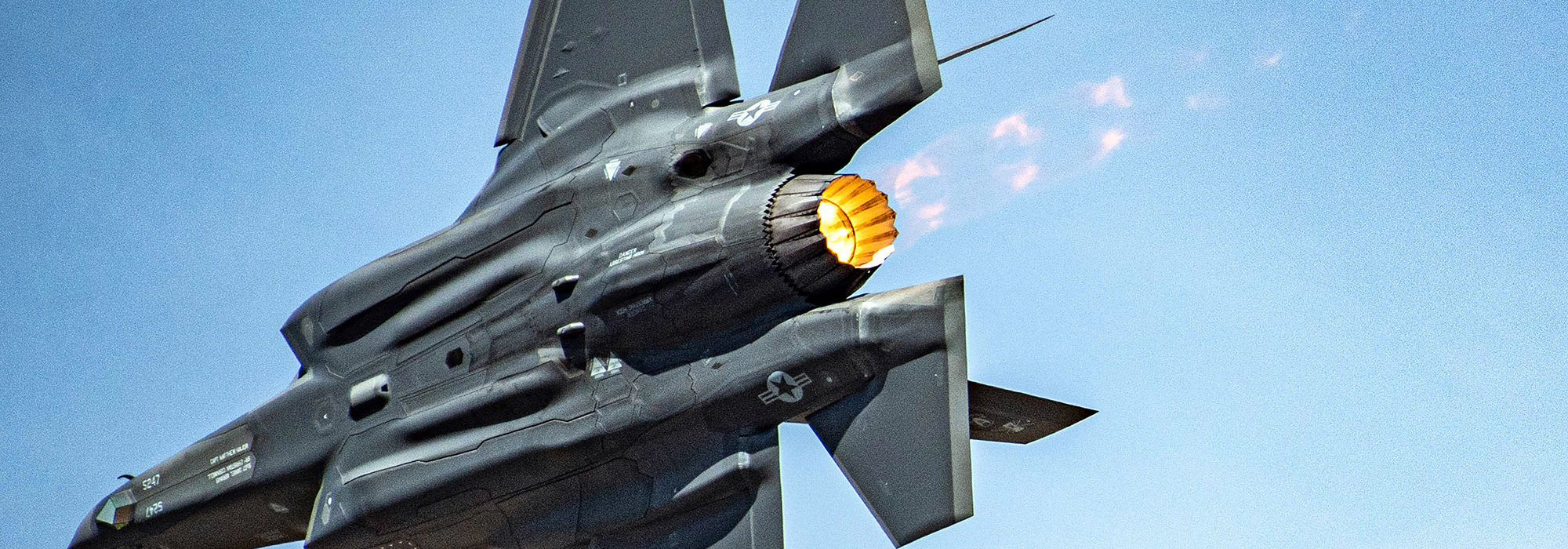

At least one of the new engines will power the Next-Generation Air Dominance fighter now in development, but there is growing interest in Congress to field new engines in the Block 4 version of the F-35 as soon as 2027. Whether that’s possible—or affordable, given all the bills the Air Force has to pay—is not yet clear. But the Block 4 F-35s, which go into production in 2023, will need a new or improved engine to make full use of its upgrades.

The revolutionary new powerplants arise from the Adaptive Engine Transition Program, run initially by the Air Force Research Laboratory and now by the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center. Based on development efforts dating back to 2007, the AETP program generated the XA100 from GE Aviation and the XA101 from Pratt & Whitney.

Both say their engines yield 25 to 30 percent more range; up to 18 percent greater acceleration; and increased cooling capability for onboard electronics. Potential other benefits include more electricity to power emitting systems and directed-energy weapons, and a reduced heat signature to improve stealth.

“We know we can do that … we’ve achieved that,” said Pratt’s military engines division president Matthew Bromberg.

GE’s David Tweedie, general manager for advanced combat systems, said his company’s engine also meets the Air Force’s goals and offers “a significant reduction in carbon emissions” as a byproduct. Tweedie said the transition from a successful technology effort to an engineering and manufacturing development program aimed squarely at installing new engines in fighters should begin now. But “everything [in the budget] beyond fiscal ’22 … is pre-decisional,” he said.

Next-Generation Propulsion

Fighter engine technology hit a wall in the early 2000s. Engineers struggled to squeeze even small improvements in thrust or range from fighter turbofan designs. Adaptive technology—which adds a third stream of airflow to the engine and the ability to adjust it—offered a way to break through that wall.

“There were three major technology efforts,” according to Tweedie. The first was adaptive technology, “the ability to reconfigure, in flight, toward either a more fuel-efficient mode or a high-thrust mode,” he said. Second was creating “the third-stream architecture for thermal management demands … unique to fifth- and sixth-generation combat aircraft.” The third was “advanced … manufacturing techniques.”

We have the ability now, I think, to create engine competition.Adam Smith (D-Wash.), chairman, House Armed Services Committee

The third stream adds an extra air path to the engine, in addition to the central path that runs through the middle of the core and a second, bypass stream. Flowing around the outside of the engine case, the third stream can be used in several ways: diverted into the center stream for increased thrust; to improve propulsion efficiency; or to cool the engine and aircraft electronics.

New ceramic matrix composites (CMCs) replace metal alloys in some critical components, offering “lighter weight [and] higher temperature capability,” Tweedie said. This enables the engines to run hotter and thus more efficiently, without sacrificing durability. Additive manufacturing—also called 3D printing—also“really helped engineers unlock the design space … to be able to answer questions like, ‘How do you fit all this into a real airplane, like the F-35?’”

Bromberg said the XA1010 has “adaptive mechanical seals,” which he said are unique to the Pratt design. These allow airflow to go “where you want it to go.”

Now, Bromberg said, testing is focused on “how long will [an AETP engine] last?”

U.S. fighter engines are already “incredibly powerful,” and Bromberg said the F135 is “invisible” to detection, but “we can make them so a pilot can use them again and again … and go years between a scheduled maintenance event.” That’s a “unique capability of the United States’ propulsion industry, and we have to keep developing it. So, we test for that.”

More Range, More Power

The operational payoffs could be huge. Besides a 25 percent reduction in fuel consumption, Air Force officials said, fighters with the new engines could gain up to 30 percent more range or 40 percent more persistence, significantly offsetting the distance challenges in the Indo-Pacific theater. Put another way, adaptive engines could help fighters reach a third more targets, from a third more airfields, and reduce their dependence on aerial tankers by up to 75 percent.

“That range improvement gives me the same effect as more fighter squadrons,” said a senior Air Force official. Being able to run hotter would also allow the F-35 to fly low-altitude missions for longer than it can today, Tweedie said. GE’s XA100 “can effectively double the thermal management capacity on the jet.”

Both GE and Pratt said they’ve tested their AETP engines successfully throughout 2021 at their own facilities, and would soon turn them over to the Air Force for further tests and data collection at the Arnold Engineering Center in Tullahoma, Tenn.

Many in Congress are sold already. The House Armed Services Committee, in its version of the fiscal 2022 National Defense Authorization Act, directs the F-35 Joint Program Office and the Pentagon’s acquisition and sustainment undersecretary to set a plan integrating AETP engines into the F-35 no later than 2027, a time frame that both contractors say they can meet.

HASC chair Adam Smith, in an Aug. 31 Brookings Institution event, said the F-35’s current engine—Pratt & Whitney’s F135—is “burning out faster and taking longer to fix than expected.” Parts backups are creating a chronic shortage of F135 engines.

Having a competing engine could stimulate improvements in cost and reliability, he said.

“We have the ability now, I think, to create engine competition going forward,” Smith said. “We are going to push [it].”

Lightning Power

In 2011, however, after great debate about the price, technology, and industrial base advantages and disadvantages of maintaining two engine vendors for one fighter, Congress acceded to Defense Secretary Robert Gates’s request to terminate the F136. He argued that it was an unnecessary expense, both to develop and because it would require a separate logistics train for the fighter. All three variants of the F-35 would use the F135.

Making a change now would be problematic, however. If the Air Force wants to use the AETP engines in its F-35s, it will have to bear the cost by itself, according to Joint Strike Fighter program executive officer Air Force Lt. Gen. Eric T. Fick. The F-35 users agreed, since the program’s inception, that “you have to pay to be different,” Fick said in September. Neither the XA100 nor the XA101 will fit in the Marine Corps’ F-35B model, which is the short-takeoff-and-landing version. The F-35B’s exhaust swivels from horizontal to vertical to enable vertical fight, but Bromberg said an adaptive engine “can’t articulate like that.”

Fitting either the XA100 or XA101 into the Navy’s F-35C carrier-based version is possible, but would also require major engineering; it would require shifting the carrier-landing variant’s tailhook apparatus.

If the new engine is “a one-service … unique solution, the cost of that solution will be borne by that service,” Fick said, adding, it would be “unfair” to ask partners who can’t use the new engine to underwrite its development and integration. Indeed, any two-engine support train will impose costs on partners by reducing commonality among them: more different parts means higher unit costs for all. Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall, speaking with reporters at AFA’s Air, Space & Cyber 2021 Conference in September, said he favors AETP engines for the F-35, but doesn’t know if that is affordable.

“We’ve had some pretty good success” with AETP, Kendall said. “We’d very much like to continue the program that advances engine technology,” but it’s “not clear” the Navy feels the same way. He said he’s still discussing it with Navy Secretary Carlos Del Toro.

Some Kind Of Change

What is clear is that the F-35 needs some kind of engine improvement, Fick said. The “first three” increments of the fighter’s Block 4 upgrade can function with the existing engine, he said, but “beyond that, we need to do something different.”The jet can’t fully exploit Block 4’s capabilities without more power.

The JPO is working with Pratt & Whitney to develop “a family of options … to give us the power and cooling we need” for Block 4 and beyond, Fick said.

As an alternative, Pratt has put together an Enhanced Engine Program (EEP), a package of F135 upgrades that can improve performance without changing out the F135’s core.

Jennifer Latka, Pratt Vice President for the F135 program, told Air Force Magazine that the company submitted the EEP proposal in March: It could provide a 50 percent boost in thermal management and a 5 percent improvement in vertical lifting power.

She said the proposal “can be tuned” to “what the services most want,” and that changes could be cut into production by 2028. The upgrade would still have “some margin” for additional capability growth.

“It is very well understood” that the F-35 needs more power and the engine will need to be modernized—“hopefully, one time over the life of the JSF program.”

Pratt’s proposed enhancements would cut 36 percent of the cost of the engine’s first shop visit, “where the big bills come,” she said. The EEP effort is separate from prime contractor Lockheed Martin’s push to cut F-35 operating costs to $25,000 per hour by 2025 (in 2012 dollars).

Latka acknowledged that the existing F135 can run hotter to meet more of the Block 4 requirements, but that would mean “the engines come in for maintenance” with more frequency, and that will drive up operating costs, long a sore spot with the JSF program. But she estimated that adding a second engine to the F-35 program would be even more expensive, costing $40 billion more over the remaining 50-year life of the F-35.

The AETP engines were “always intended” to power sixth-generation fighters like the NGAD, she said.

Boosting the Air Force’s Legacy Engines

Third-stream AETP technology can’t be backfitted to previous engines such as the Pratt F119 that powers the F-22 fighter, or the Pratt F100 and GE F110 that power F-15s and F-16s. The engine space in existing fighters won’t accommodate the larger-diameter powerplant.

However, “other mechanical systems” that went into creating the AETP can, said Matthew Bromberg, Pratt & Whitney military engines president. In fact, up to 70 percent of AETP technology “could be leveraged” into previous engines, he asserted, although those improvements would have to “buy their way in” by improving performance enough to justify the investment.

Still, “every future engine that we design will leverage that entire technology suite,” Bromberg said. The Air Force agrees. Gen. Arnold W. Bunch Jr., head of Air Force Materiel Command, told reporters in September that the service is excited to extract all the “goodness” it can from the AETP program for earlier engines.

While AETP technology writ large may not be portable to older engines, “if we can make an advance, even if it’s a subcomponent or a manufacturing methodology … we want to take all those things we can get to the max performance we can,” Bunch said. He’s got his engines directorate looking at whether “we can scale it” to larger or smaller airframes, and what trade-offs that might entail.

Whatever is decided about AETP applications, engine technology must move forward, Bunch said.

With his background in technology development, test and operations, “it’s technology that I really believe we need to invest in, and continue to keep the industry up to the latest standards that we can capitalize on.” The U.S. has a “decided advantage” in propulsion technology today, and the Air Force has determined that it must retain that edge, Bunch said.

“There’s a significant amount of risk that comes with brandnew technology,” she added. Before counting on the AETP to deliver the future of F-35 propulsion “a tremendous amount of validation” would have to be done. In her view, “The AETP is not the right fit for the F-35.”

But Bromberg, Latka’s boss at Pratt, said the company is “thrilled” about having two options to offer the Air Force and the F-35 Joint Program Office. “We’d love the opportunity to …obsolete ourselves,” he said. “Now the debate is focusing on modernizing the Joint Strike Fighter. And we think it’s a good time to have that debate.” Each solution has its “advantages and disadvantages,” he said.

Bromberg said he charged the F135 team to borrow what they could from AETP, such that the resulting EEP product “is suitable for all partner countries … [is] weight-neutral … [and] production cost-neutral.” It also needed to offer sustainment cost advantages and be “cut into production” in a “very low risk way.”

Lockheed Martin, builder of the F-35, has worked with both GE and Pratt on their AETP research, according to company aeronautics executive vice president Greg Ulmer. Lockheed generates requirements for fighter power, but has no favorites among the propulsion options, he said. The Block 4 needs more power and cooling, but he’s agnostic about how that’s achieved. Engine and airframe integration analysis is “always in work … it’s recurring,” Ulmer said. “We’re constantly looking for ways to improve fuel efficiency on the platform.”

Tweedie said Lockheed has been “an active participant” in AETP “since Day One.” The companies have been working collaboratively—but not exclusively—“for the last eight years to ensure that our design integrates with their vehicle, not just where it was in 2011, when the F136 ended, as the [aircraft]

has evolved.”

Gen. Mark D. Kelly, head of Air Combat Command, told reporters the choice between an upgraded F135 and the AETP GE Aviation will have to be weighed in the context of “capability, capacity, and affordability. And we’ll measure it across those three lines of effort and come up with the right solution.” Fick pointed out that even if the Air Force goes with an AETP solution, the enhanced F135 will still be needed to ensure that “we’ve got everybody covered.”

With 700 F-35s now flying, and more than 100 more coming each year for the next five years, “that’s 1,200 aircraft before I field an advanced engine,” Fick said. Those aircraft will still need to be supported.

Whatever the Air Force and the F-35 partners decide about the F-35’s engine, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. insists it’s critical to continue propulsion research “so we do have options in the future.”

The language from Congress about using the new engine technology in the F-35 is “really in line with what we’re trying to get done” to make the F-35 “more affordable and make the sustainment costs more reasonable.” The Air Force significantly reduced AETP funding in its fiscal 2022 budget request, but included it among its “unfunded

requirements.” Congress appears poised to restore funding to the program.

Tweedie said GE is encouraged by Brown’s comments and Congress’s push. If the AETP is allowed to close out without advancing to an engineering and manufacturing development program right away, “there’s a lot of cycle time that’s lost if you bring it to a complete halt and then try to restart.” Having an edge in fighter propulsion is “not a birthright,” Tweedie said. “We have to earn that.”

The investment in AETP “burned down the risk” in making the next generational leap in propulsion technology, he asserted, and the industry is ready when the Air Force decides how to move forward. “It’s our turn now to deliver that to this and future generations.”