America’s fighter advantage has long been powered by superior engines. Here’s what the future holds.

The Air Force is now planning to pass on fitting its F-35A fighters with all-new engines, choosing instead to upgrade the engine core. While Congress could still change that plan, USAF has opted to wait to apply advanced Adaptive Engine Technology to its Next-Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) Fighter.

There’s not much time to get the job done. The NGAD is slated to be operational around 2030, meaning test flights will need to start circa 2028 or sooner, so its the Next Generation Adaptive Propulsion (NGAP) engine needs to take shape quickly.

“With the way we’re funded, we think we can carry both” GE Aerospace and Pratt & Whitney, “through prototype, and both are leaning-in fully,” said John R. Sneden, propulsion director for Air Force’s Life Cycle Management Center.

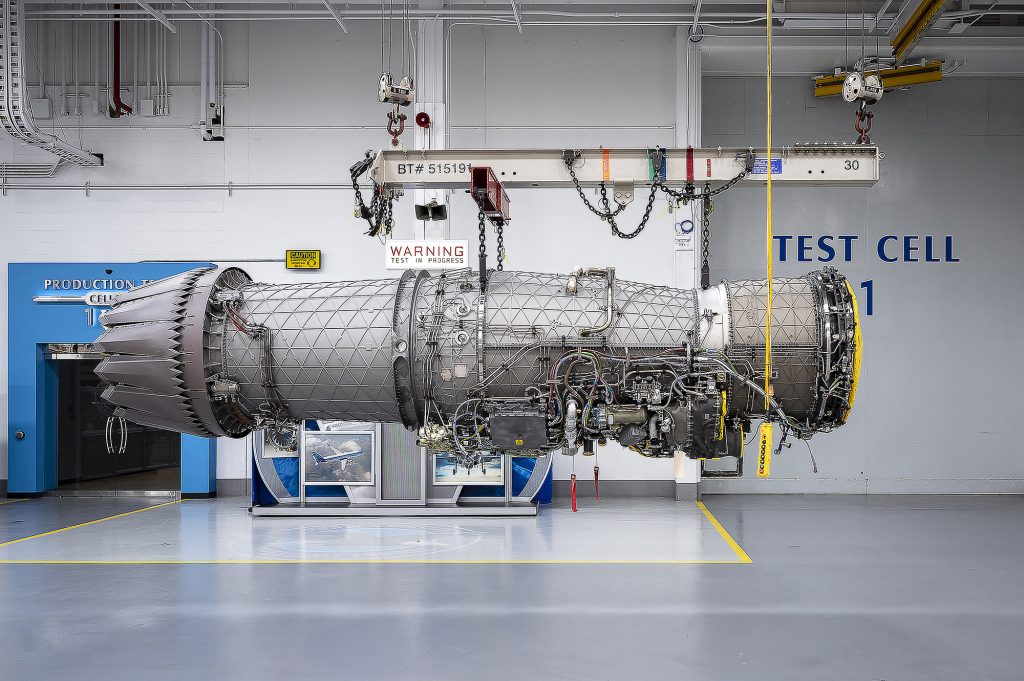

AFLCMC Propulsion Director John SnedenWe’re doing the detailed design activities right now. And within the next couple of years, we’ll be moving into prototyping and testing.

Speaking with the press at Air Force Materiel Command’s Life Cycle Industry Days in July, Sneden said the Air Force will contract for a prototype NGAP from each of the two fighter engine companies. It may then keep both in the competition through preliminary design review, or pick one early if it proves to be the obvious superior performer.

“We still have that opportunity to do a downselect if we start seeing … [a] huge separation between the two,” in terms of performance, Sneden said. A previous plan had called for picking the NGAP contractor based on digital proposals alone, and while it will still be designed that way—Sneden said it will be the first digitally-designed engine in USAF’s fleet—there will be physical prototypes.

Sneden said aircraft primes Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman all received nearly billion-dollar NGAP contracts last year—as did GE and Pratt—to harmonize the engines’ performance with NGAD airframes. The work will ensure there’s “an interface methodology between the airframe company and the propulsion company,” he said. Northrop affirmed in August, though, that it will not bid on NGAD.

While he wouldn’t provide details of the NGAP’s timeline, Sneden said “we’re doing the detailed design activities right now. And within the next couple of years, we’ll be moving into prototyping and testing.”

The Air Force requested nearly $600 million for NGAP work in fiscal 2024, an increase of $375 million versus the fiscal 2023 amount.

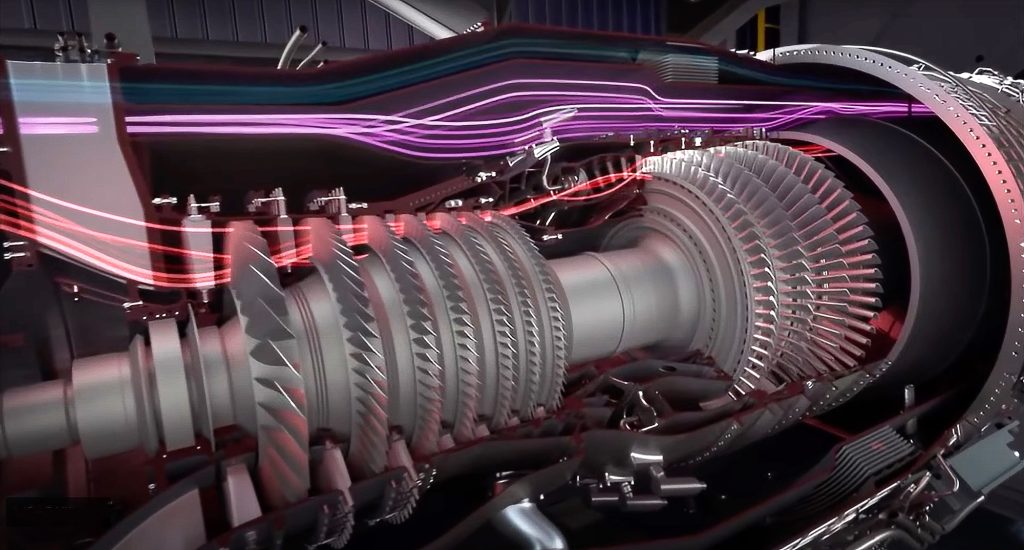

NGAP will build on the technologies developed by GE and Pratt in their Adaptive Engine Transition Program (AETP) engines; respectively, the XA100 and XA101. Those engines—which pioneer a new, third-stream air path that allows efficient switching between fuel-efficient cruise and high-performance thrust—were developed over a decade ago with an Air Force investment of more than $4 billion. The idea—now nixed—was to put them in the F-35, to upgrade its performance, range and reliability at the midpoint of the fighter’s service life.

The adaptive airflow concepts, ceramic matrix materials, advanced composites, thermal management improvements and additive manufacturing technologies for critical components developed in AETP will “port” directly to the NGAP, Sneden said.

“It’s not lost,” he said, “it just gets incorporated.” Had there been no AETP, there would be no NGAP, he said.

The NGAP engines will be “differently sized” than the AETP, Sneden said. The revolutionary F100, which powered the early F-15s and F-16s, had a fan diameter of 34.8 inches, but the diameter of the F135 and the AETP is 46 inches. The AETP was meant to fit in the F-35.

Asked to elaborate, Sneden later relayed through a spokesperson that “as with any new weapon system development, the NGAP propulsion systems will be sized appropriately to meet thrust, weight, and other integration requirements.”

But the “technology baseline” for NGAP and AETP “is essentially the same.”

Tough Choices

The AETP engines would have delivered the most improvement in fighter engine technology in a generation, with double-digit gains in on-demand thrust and about 30 percent improvement in fuel efficiency. They were intended to provide the F-35 with the thrust, persistence, and electrical power that fighter will need for its Block 4 upgrade.

But the Air Force opted instead for Pratt’s Engine Core Upgrade, or ECU, along with a Power and Thermal Management System (PTMS) improvement.

The ECU and PTMS are supposed to be ready for installation circa 2030, about the same time NGAP must be ready for production.

Passing on AETP wasn’t easy, Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall said in March, and the choice still concerns him.

Choosing the ECU over the AETP “was the right decision, given the constraints we have,” but one that “I worry about, a little bit,” Kendall said. He called the AETP “unaffordable” because “the only service that wants the new technology is the Air Force right now, and we can’t afford it by ourselves.”

The agreements covering the F-35 program’s 10 international partners as well as the U.S. Air Force, Marine Corps and Navy require any user that wants a unique capability on its F-35s to bear the cost of developing and integrating it.

Kendall said in 2022 that he tried unsuccessfully to talk Navy Secretary Carlos del Toro into coming in on AETP. Radical redesign would be needed to make an AETP fit the Marine Corps F-35B—which has a unique vertical landing system—and significant revision would be needed for the Navy’s carrier-landing F-35C variant, as well.

Still, Kendall said, “if we had the opportunity to reconsider that, I think that would be something I’d like to have another shot at.

The F-35 Joint Program Office (JPO) endorsed the ECU as the least disruptive and most economical choice for the bulk of F-35 users, as it would avoid the need for a new and separate logistics train and parts inventory that an AETP would require. In a statement to Air & Space Forces Magazine, the JPO said it “stands behind our in-depth business case analysis, conducted in partnership with industry, that helped inform” the Pentagon’s choice. And even if the AETP had been chosen, the Power and Thermal Management System (PTMS) would still be needed.

The JPO held an industry conference in June to discuss a possible competition for the follow-on system, needed to improve engine life and to cool the electronics-intensive elements of the Block 4 upgrade.

The ECU and PTMS “restores engine life”—which has been burning up faster than expected because of the way the F-35 is used—and meets F-35 user needs for cooling and power, as well as their “budgetary…requirements,” the JPO said. The upgrades will “ensure the F-35’s propulsion system is prepared for future demands that will be necessary to stay ahead of our near-peers.”

Family Feud

A heated row erupted between F-35 prime Lockheed Martin and Pratt following the Paris Air Show in June, when Lockheed Aeronautics Executive Vice President Greg Ulmer broke the company’s long silence about its power preferences for the F-35.

The F-35 will undoubtedly undergo not just a Block 4 upgrade but a “Block 5, 6, 7, and 8,” Ulmer told defense reporters, as it will likely serve into the 2070s or beyond. It will need steep performance improvements, arguing that the threat, not the cost, should drive F-35’s power requirements.

In a statement to Air & Space Forces Magazine, Lockheed said that to stay ahead of peer threats—read China—“the F-35 will need even greater capability, readiness, range and thrust, which will require an upgraded engine.” Neither Ulmer nor a company spokesman stated a Lockheed preference between the two AETP options.

Responding, Jeff Shockey, senior vice president for global government relations at RTX, Pratt’s parent company, said Ulmer’s comments are “undermine” the Pentagon’s decision process regarding the ECU. He charged Lockheed with trying to market the F-35 “as a sixth-generation fighter” in order to “negate the need for a sixth-generation fighter competition,” in an effort to “extend the life and longevity” of the F-35 contract. Shockey said Ulmer was trying to “pull a fast one on Congress.”

The ECU option, of course, preserves Pratt’s own monopoly on F-35 power and likely locks out GE from getting any F-35 work for the balance of the program.

Asked if the public dispute imperils the F-35 program, JPO Program Executive Officer Lt. Gen. Michael J. Scmidt said through a spokesperson that “we expect all our industry partners to work together to achieve the requirements that are set by [the Defense Department] to ensure our warfighters have what they need to accomplish their missions.”

The spokesperson declined to say if Schmidt has tried to smooth things over between his two biggest contractors, saying only that the JPO “communicates with our industry partners routinely.” The JPO contracts separately for the F-35 airframe and the Pratt F135 engine, which is supplied as government-furnished equipment to Lockheed.

Sneden wouldn’t address whether the AETP could be put on the shelf for a future F-35 upgrade. He would only say the Air Force “has made its decision” and the focus now is “just to get the technology to a logical transition point” for NGAP.

The Air Force will choose one NGAP engine that will fit in any of the airframes competing for the NGAD, Sneden said, ruling out a replay of the “Great Engine War” between the two companies in the 1980s, when the Pratt’s F100 competed with GE’s F110 to power F-15s and F-16s. An attempt to re-run that competition in the 2000s between Pratt and GE was stillborn when the Pentagon terminated the competitive engine program: GE’s F136 powerplant, which offered somewhat different technology from the F135.

While some optimization of NGAP may be needed to match the winning NGAD bidder, Sneden said all the contenders are abiding by “the propulsion constraints that we’ve studied, and evaluated, and provided to each.”

A Fragile Industrial Base

The NGAP is a “critical” program for the Air Force, Sneden said, as competition will not only spur contractors to offer better and more affordable options, but also because the engine industrial base is fragile.

“Not many companies in the world can do this,” Sneden said.

Adaptive technology is the next step in fighter propulsion, he asserted. Adaptive technology is “our assurance of long-term air dominance and propulsion superiority.”

The fragility of the engine industrial base, Sneden noted, stems from the few-and-far-between new fighter engine programs, and acquisition policies that favored low cost over capacity. Pursuing one new engine every 20 years or so isn’t a recipe for maintaining the industrial base’s capabilities, he continued.

The propulsion directorate is focused on maintaining the edge “we currently have” and that means “continuing to fund both vendors for as long as we possibly can.”

While the U.S. fighter engine industrial base is “very capable,” it doesn’t move “in a threat-relevant cadence,” Sneden observed. “It takes us about 10 to 15 years to put a new propulsion system out to the field.”

But, “in fairness to my industry partners, they haven’t really been challenged or incentivized” to accelerate that tempo, given the nature of the contracts they’re asked to fulfill, Sneden stated.

“The sole-source nature of our enterprise … exacerbates that same problem by removing some of those competitive forces that drive innovation, speed, and cost control,” he said.

Sneden also said the propulsion directorate is working with engine companies to accelerate their processes, which have followed the just-in-time model over the past three decades.

“That’s not … satisfactory, it needs great improvement,” he said.

Inflation is eating away at buying power for government and industry alike, he commented, “so it’s now harder to maintain the same readiness with comparable amounts of budget you’ve had the previous years.” This is driving a focus “on cost-effective readiness and securing the budgets that we need to ensure that … the warfighter can fly, fight and win,” he said.

He also said the industry and government have digital transformation efforts underway, but they are “not as pervasive as they need to be, which results in longer lead times and more costly efforts.”

China, China, China

Sneden said the Air Force’s propulsion enterprise needs to be seen in the context of a rising China. Beijing is rapidly gaining prowess with fighter engines, after decades of slow advance and having to import technology from Russia.

“We are losing our propulsion lead to China,” Sneden said flaty, because Beijing is “investing heavily in developing and producing effective propulsion technologies.”

China has overcome its fighter engine struggles by gaining new facility with single-crystal structure in their materials, Sneden said. Beijing’s “intellectual property theft, working with Russia, and frankly, just their own development, activity, and … budget” have made China a formidable competitor.

Beijing’s investments “are significantly greater than ours from a propulsion perspective, so it’s allowed them to close the gap,” he elaborated. China has made “significant leaps and bounds over this last roughly eight-plus years,” Sneden observed, adding that “our focus is not letting them” close the gap.

Back to Congress

Congress has not yet decided whether to skip the AETP and move on to the NGAP. Rep. Rob Wittman (R-Va.) inserted language on the House version of the 2024 defense bill requiring that AETP work continue, to the tune of $588 million. The Senate seems inclined to add up to $280 million for advanced engine technology development, as a way to generate work for the engine industrial base. In the Senate Appropriations version of the bill, that committee expressed its concern that “a skilled workforce across the domestic military aircraft engine industrial base will degrade if sufficient work and the requisite funding are not available.”

“Everything we’re seeing” indicates that NGAP will be funded, Sneden said. Focusing solely on the AETP for the F-35 without advancing the technology for NGAD would be “a waste.”