Five years after the most recent military retirement overhaul,

we still don’t know if it will help or hurt retention.

The Defense Department introduced the most momentous change in its retirement system in January 2018. The new Blended Retirement System (BRS) is now five years old, and its consequences remain hard to decipher.

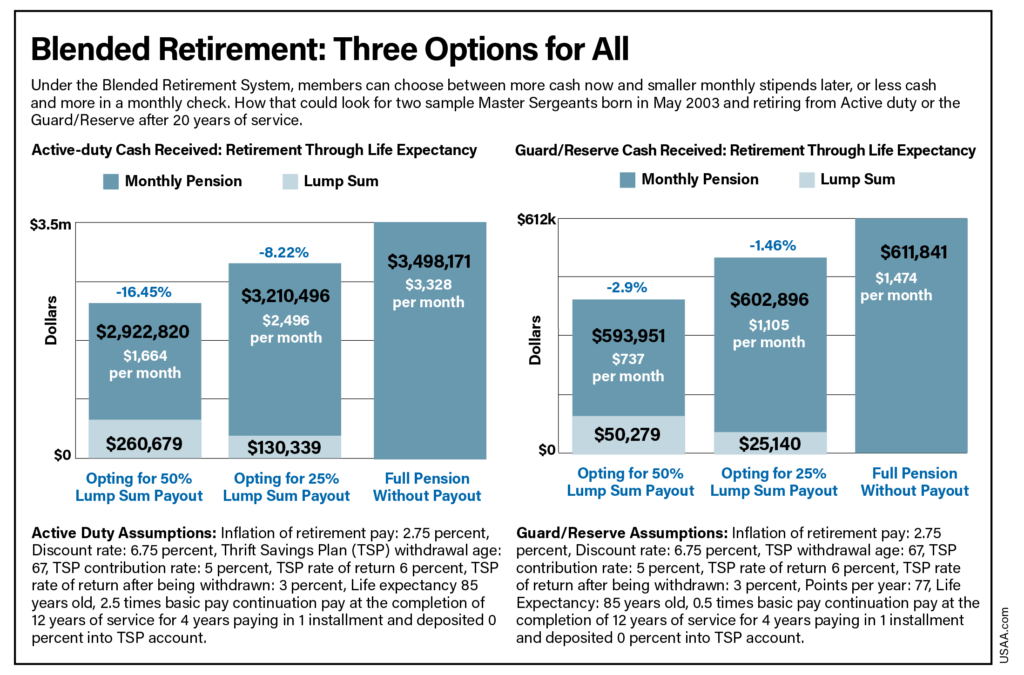

The first Airmen to opt into Blended Retirement are still at least three years from being eligible to retire themselves, so it’s still too early to grasp the results of their choices, and the wisdom of those choices given hindsight. At its root, those choices boiled down to whether it was better to select a rapidly vesting payout in the Thrift Savings Plan (TSP) and reduced monthly retirement pay in the future, or a lump-sum payout at 20 years

For most Airmen, particularly enlisted members, BRS was a boon: Because only about 17 percent of those who join the service ever stayed long enough to retire, the vast majority of members left service with nothing but their personal savings. Now, instead of walking away empty-handed after four, six, or 12 years or more, every departing veteran will have accumulated thousands in retirement savings in the Thrift Savings Plan—what amounts to a military version of popular civilian self-directed retirement systems known by their tax code chapter as 401(k) plans.

With military recruiting and retention flagging in the aftermath of the pandemic and the end of the long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the question of whether the new system will help or hurt retention looms over the entire enterprise. Pentagon officials maintain the new retirement system has a neutral impact on retention, but that is yet to be proven. Meanwhile, some see missed opportunities in how the services can leverage the system to their favor amid a military-wide recruiting crisis.

Lisa Lawrence, DOD spokeswomanIt will take several years for the retention impacts of the BRS to be fully understood.

The Air Force Academy’s Office of Labor and Economic Analysis has studied the issue, tasked by the Pentagon to analyze its impact on retention, said DOD spokeswoman Lisa Lawrence.

“Our expectation is that it will take several years for the retention impacts of the BRS to be fully understood,” she wrote in response to questions. “Their preliminary analysis shows that the BRS is having little or no effect on retention to date.”

The military’s World War I retirement formula—50 percent of final basic pay after 20 years—endured through two World Wars, Korea, and Vietnam. It underwent two overhauls in the 1980s. In September 1980, with the passage of the 1981 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), the formula was shifted to “High-3,” a slightly reduced formula that awarded retirees 2.5 percent of average basic pay over their highest 36 months of service—provided they served at least 20 years. Those serving 20 received 50 percent of their High-3 average, and those staying 30 received 75 percent of that average. This formula eliminated a common practice of waiting to retire until Jan. 1 or shortly after, once the next year’s pay raises kicked in.

Six years later, Congress returned to the issue, introducing “REDUX,” in August 1986. Under REDUX, the formula was reduced to 2 percent per year for the first 20 years—or 40 percent of High-3—then 3.5 percent for each additional year up to 30. This preserved the 75 percent threshold for members who stayed 30 years. Effectively, this reduced the value of most retirees’ pensions, while preserving the value for the highest-ranking and longest-serving officers and enlisted members.

Little thought was paid to the matter for the next decade. But as members who joined after 1986 approached 10 to 12 years of service and began to consider the implications of staying versus leaving for civilian careers, it became clear to many that their retirement was not worth what they believed. Military retention sunk and the Pentagon and Congress pressed to fix the problem. The 2000 NDAA repealed REDUX, providing service members a choice at the 15-year point in their career: They could stick with REDUX and accept a $30,000 retention bonus, or they could switch to High-3.

The retention bonus was derided by some as “the Corvette bonus,” a bad deal for most given normal life expectancies and the greater value of High-3. But for some members looking to buy a home, finance a business, or send kids or spouses to college, it proved a boon. Retention improved. Concerns faded, but not for long.

In 2011, the Defense Business Board, an advisory panel reporting to the Secretary of Defense, noted how few military members actually save anything for retirement, noting in particular that while 43 percent of officers ultimately reached retirement eligibility, only 13 percent of enlisted members did the same. Effectively, the retirement system was weighted toward officers. Worse, the board argued, the system as constructed “appears increasingly unaffordable.”

Beth Asch, a senior economist at the Rand Corp. and a leading scholar on military retirement, said offering the lure of 20-year retirement to young recruits was inefficient, because they tend to “discount the future very highly.” A second issue was the “cliff-vesting” problem: After reaching the 20-year mark, the financial incentive to remain in service dried up for many, and retention dropped steeply. The increased joint service assignment requirements generated by the Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986 had effectively shortened officer assignment lengths, Asch said, meaning they had to “cram” more assignments into the same period. It made for an unforgiving timeline.

The legacy retirement system did not distinguish between highly physical jobs that make serving 20 years harder and administrative positions that inflict no such problems on troops’ bodies, and thus career lengths tended to vary by military specialty and career fields.

“It was like winning the lottery, practically,” Asch said of securing military retirement. “In general, it was considered unfair, because only a fraction of the force would get the benefit.”

A Government Accountability Office report had concluded the same thing in 1978 and called for “some form of vesting for members who do not complete full careers.”

But not until the 2016 NDAA did Congress act, creating the Blended Retirement System. BRS would become standard for all troops entering service after Jan. 1, 2018, providing a hybrid benefit: All troops are automatically enrolled in the Thrift Savings Plan after just 60 days of service. From that day, the government contributes an amount equal to 1 percent of members’ basic pay to each member’s account. In addition, service members can contribute as much as they want to their TSP accounts; the default is 5 percent, but can be changed at any time. After two years of service, the government will match, dollar for dollar, service members’ contributions up to 5 percent. When members leave, they take that retirement savings with them.

Between eight and 12 years of service, when many might be choosing between making the military a career or transitioning out, BRS dangles a new incentive to stay: In exchange for committing to serve at least three more years, the military will pay a cash bonus. For Airmen and Guardians, that amount today is equal to at least 2.5 times monthly base pay for those on Active duty, and half of monthly basic pay for Guard and Reserve members.

At 20 years, members become eligible for a traditional retirement, but valued at the REDUX rate of 2 percent per year, or 40 percent of basic pay after 20 years. The theory is that this pension, coupled with TSP savings, is a better deal for everyone. When BRS was introduced, service members who’d served fewer than 12 years as of Dec. 31, 2017, were given until the end of 2017 to make a choice: They could opt into the new retirement plan or remain with the High-3 system.

For Spencer Reese, taking the BRS deal required little thought. An Air Force C-17 Globemaster instructor pilot at the time, he wrote a book called “The Military Money Manual” and today maintains a website of the same name. He felt so strongly about the decision to switch that he shared his thinking in a column for Military.com’s Paycheck Chronicles blog to encourage others to do the same. For troops with at least 10 years of service, even those headed toward retirement, he wrote, banking on the 20-year payout was too great a risk.

“In the current system, you or I could serve for 16 years, not promote to major or lieutenant colonel, get passed over for continuation, and get forced out,” he wrote. “Under the new system you would at least have your TSP account with all the matching that had gone into it, plus the continuation pay bonus paid at the 12-year mark.”

Reese was a captain with eight years of service at the time; he left Active duty in 2022 as a major with just shy of 12 years. He told Air and Space Forces Magazine he’s happy with his choice.

“Especially in my cohort, which was Air Force pilots, a lot of them are getting out before 20 years, because the airlines are having a huge hiring boom,” he said. “And so, at least with my peers and the group that I have the most interactions with, those who opted in are glad they opted in, because they’re now off Active duty.”

While Reese said he never planned to stay 20 years, he knew that he’d get a 40 percent pension, plus the funds accrued in his TSP had his plans changed.

“In my final full year of Active-duty service, which was 2021, I had $3,688 of matching put into my TSP account,” he said.

Safely nested in a tax-deferred account today, he expects that to be worth well over $20,000 in 30 years.

Missed Opportunities

How people respond to new concepts like BRS is always a question. RAND predicted take rates of 70 percent to 100 percent for enlisted Airmen with fewer than eight years of service, and upwards of 50 percent for officers. But when the Pentagon finally released opt-in data in early 2019, it showed take rates well below half for every military service except the Marine Corps. (The Corps typically retains just 10 percent of first-term Marines, an intentional force design consideration driven by its structure. But tellingly, the Marines also were the only service to require Marines to make a selection; the others required an affirmative choice to select BRS, and otherwise defaulted their choice to the legacy plan.)

In the Air Force, the opt-in rate was 29.1 percent, only slightly more than the Army (25.5 percent) and the Coast Guard (21 percent). The Marines opted in at a 59.4 percent rate.

“What I always felt was the big shame of it, aside from the fact that we got it wrong, which was embarrassing, was that it was a shame that there were people for whom it would have been a better decision,” Asch said. “Then they would have left the military with at least something in a Thrift Savings Plan.”

Air Force spokeswoman Tech. Sgt. Deana Heitzman said individual decisions are complicated and personal. “Numerous factors impact an individual service member’s decision related to the BRS,” she said in an email. “The [Department of the Air Force’s] primary focus during the opt-in period was ensuring every member was fully informed, educated, and had the resources and information necessary to make a decision that best fit their personal situation.”

Interestingly, however, allowing a default decision enabled members to ignore that education and let inertia be their guide.

Those who find themselves, by choice or inaction, excluded from BRS, do not qualify for the continuation pay incentive, which could become more potent than it appears today. While Congress set the minimum at 2.5 times monthly base pay, the military services have the authority to increase that to up to 13 times monthly basic pay, and to target that bonus to specific specialties as needed. In the Air Force, where pilots, cyber specialists, and others are in short supply, that could prove a powerful additional incentive.

Driving this rate flexibility is a revealing detail from RAND’s analysis: BRS was projected to have a negative impact on officer retention. For officers, cliff vesting was so attractive that many stayed longer than they would have preferred rather than leave with no retirement nest egg.

In fact, for BRS to achieve retention parity with the previous system, estimates indicated the services might need to pay continuation pay bonuses of 10 to 12 times monthly basic pay—near the maximum set by Congress.

“In other words, you had to give an officer a year’s worth of basic pay, not two-and-a-half months,” Asch said. “And the services opted not to have a higher multiplier for officers. Maybe they felt like they weren’t having retention problems with officers.”

That may change. The Space Force is still too new to have any real retention data to show for itself, and the Air Force is in the midst of significant changes to officer advancement. The Air Force ended accelerated “below-the-zone” promotions for officers in 2019, and the consequences of that decision on retention won’t be fully understood for several years. Other changes to the career development system are still underway.

Meanwhile, the Air Force has made no progress in reducing a chronic shortage of about 2,000 pilots across the Active, Guard, and Reserve components. A return to robust airline hiring has not helped, and efforts to accelerate pilot training are still too new to have an impact.

Recruiting Shortfalls

These days, recruiting problems are of primary concern for the services, but when recruiting struggles, retention is another lever that can be adjusted. The Marine Corps has begun to retain more of its Marines, for example. Interestingly, Marine Commandant Gen. David H. Berger cited BRS in 2021 as hurting retention efforts, according to USNI News. The Army missed all its targets in 2022. The Air Force made its Active-duty recruiting goal for 2022 only by drawing down its delayed entry pool; it fell short of Guard and Reserve targets.

The Air Force has seen “no notable trends” linking BRS to retention, Heitzman said.

For the Air Force, while the pilot community continues to contend with longtime shortages, overall retention is robust, and in fact trending higher than typical amid pandemic recovery and continued job market uncertainty. The Air Force disclosed in December 2022 that 93.1 percent of officers and 89.4 percent of enlisted Airmen were retained in 2022, a slight decline from 2020, but still above pre-pandemic levels.

Tobias Switzer, an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security’s Military, Veterans, and Society Program (and also an Air Force officer), said he worries that the Air Force will not be able to respond fast enough if retention suddenly changes.

“One of the problems is waiting until retention hits rock bottom, when there’s a mass exodus of service members. Then it’s kind of too late to attempt to turn the dial back on,” he said. “It’s not like an on/off switch. … And waiting until people start exiting, it kind of can be too late to then start trying to dial up continuation pay rates and offer them earlier. So I see that as potentially a tool that the services have not fully exploited to use for retention purposes.”

Indeed, given USAF’s history of asking Congress to increase the aviation bonus cap for pilots, it’s curious that the service has thus far chosen not to use the continuation pay tool to its full effect.

A final what-if has to do with the underutilized BRS opt-in window. The disparity between the Marine Corps response rate and that of the other services indicates better education and a more deliberate approach might have resulted in more troops choosing the new system.

Asch compared the rollout of BRS with a similar program for government workers, the Federal Employees Retirement System, or FERS, which was introduced in 1987. As with BRS, there was a limited opt-in period for some employees who would otherwise be grandfathered into the old system. When the stock market began to boom a few years later, spurred by the 1990s dot-com era, many of those who missed the window regretted their choices. Congress ended up reopening the opt-in window for FERS in 1998.

“Maybe there’s an opportunity for rethinking opt-in,” Asch said.

In fact, the idea has already been proposed. In 2020, Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.) called for reopening BRS enrollment, describing the initial response as “lackluster” and citing a Government Accountability Office study showing that only about one-third of troops passed a required opt-in education course on the first attempt.

That bill didn’t get far, but it’s not be too late for someone to introduce it once again. The most junior troops remaining in the legacy system are now in their second enlistment or service contract.

Reese, who emphasized the need for better and more consistent financial education for troops across the span of their careers, said he doesn’t see a downside to giving troops a second chance.

“Why not?” he said. “I think giving troops more flexibility with their finances is always, always a good move.”