There are no options over water. And the farther out you go, the longer it takes to get back.

The bulk carrier Port Kyushu stretches the length of two football fields, but it looked like a toy against the vast, dark tablecloth of the Pacific Ocean. Peering down from the window of a C-130, Staff Sgt. Mike Scheglov offered up a simple prayer:

“I really hope that they speak Russian.”

About five hours earlier, Scheglov had been working at Moffett Field, home of the California Air National Guard’s 129th Rescue Wing. It was the morning of Oct. 9, and Airmen were preparing to pick up a patient from a ship 500 miles off the coast of San Francisco. As an aircrew flight equipment specialist, Scheglov was prepositioning their gear when his supervisor asked an unusual question.

“Did you bring your lunch today?” Scheglov recalled.

The rescuers needed a Russian speaker to communicate with the ship captain. A native speaker, Scheglov was a perfect fit. He grabbed his lunch.

The 129th Rescue Wing is one of few organizations on Earth that can rescue patients hundreds of miles offshore, thanks to its fleet of HC-130J fixed-wing aircraft and HH-60G helicopters. The HC-130Js refuel the helicopters via long hoses that trail behind the wings midflight, where an HH-60G plugs in with a long probe sticking out the front of its fuselage.

Air refueling extends the range of the helicopters, letting them hoist patients out of anything from a fishing boat to a cruise ship hundreds of miles out at sea, then bring them back to hospitals ashore. But it’s a high-risk job, said Lt. Col. Christopher Nance, who commanded the Port Kyushu mission.

“There are a lot of moving parts in a helicopter,” said the HC-130J pilot. “If you’re flying over land, helicopters can find a field to put it down or C-130s can find an airfield, but there are no options over water. And the further out you go, the longer it takes to get back.”

Once the aircraft reach the target vessel, they lower a pararescue jumper (PJ) with a hoist, then reverse the procedure to pick up the patient. A blend of commando and expert medic, PJs are trained to save lives under fire anywhere on Earth, but dangling from a helicopter over a moving vessel in the open ocean is dangerous for anyone.

“Anytime you put a human being out the back of your aircraft, that is immediately high risk,” Nance explained. “There’s just so many complexities to the mission.”

There’s also the fatigue of flying for hours at a time, often in darkness, sometimes low to the water, and usually while wearing airtight anti-exposure suits. The suits are designed to keep the Airmen alive if they bail into the frigid Pacific, but they can get pungent and uncomfortable after a 10- or 11-hour sortie, said Senior Airman Reese Williamse, a special missions aviator (SMA) who works in the back of the HH-60. That’s led to a colorful nickname: “Poopy suits.”

Such challenges are nothing new for the 129th RQW, which has been flying open ocean rescues since 1975. The halls of the Moffett squadron buildings are lined with orange life buoys given to them by the crews of the dozens of ships from which they’ve rescued patients. The Port Kyushu mission would mark the wing’s 1,165th life saved, a number that includes deployments and non-ocean rescues.

“We’ve done it so often here that, to be honest, we’re really good at it,” Nance said. “So our comfort level is quite high compared to other units that may not have accepted a mission like this because it was too high-risk.”

The Crew

The call for a rescue came in from the U.S. Coast Guard on Tuesday, Oct. 8. A middle-aged man on the Port Kyushu was having what would later be diagnosed as an urgent neurological problem. The wing asked not to print exact details out of concern for his privacy, but at the time, the patient was generally unresponsive and not accepting food or water, so his crewmates worried he would not survive the voyage.

A rescue would risk four aircraft and more than 20 lives to save one, but medical experts and wing leadership deemed the gravity of the situation greater than the risk. There was no issue finding volunteers.

“Sometimes we get guys out of state that are like, ‘Hey, I’ll fly in,’” Nance said. “You get guys who will definitely take a day off of work to come out and support one of these.”

But there was a problem: The wing needed two HC-130Js to cut down on risk and haul all the gas necessary for the long flight, but due to maintenance issues only one was ready to fly. The next closest HC-130J unit is the Active-duty 79th Rescue Squadron at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Ariz., which had just spent the past two weeks on the East Coast responding to Hurricanes Helene and Milton. Nevertheless they answered the call, sending two C-130s just in case, while the colocated 55th Rescue Squadron sent two HH-60Ws if needed.

“When you’re dealing with long range over water, you want to have spares,” Nance said. “It’s a testament to the joint force that, one, they were willing to respond after everything they’d just gotten back from, and two, how seamlessly they integrated with us.”

At around 11 a.m. Oct. 9, the aircraft took off for the Port Kyushu, which would be about 500 miles offshore by the time they rendezvoused. Both HH-60Gs and one of the HC-130Js came from Moffett, while the other HC-130J came from Davis-Monthan.

“I wasn’t nervous or stressed because I knew all the guys in the other planes, and they’re all professionals,” Nance said. “They know what they’re doing.”

The Gear

A rescue package does not travel light. Besides the anti-exposure suits, the helicopter crews and PJs wore orange inflatable life preservers, sometimes called “water wings” or “Cheetos,” and carried tiny bottles of compressed air to breathe from in case, due to a crash, they had to escape a sinking helicopter.

On top of that, the PJs brought IV fluids, drugs, oxygen, blood pressure cuffs, monitors, a litter, and enough medical supplies to fill the bed of a pickup truck, all squeezed into a helicopter cabin not much bigger than a hot tub.

It gets even more cramped with a patient aboard. One of the PJs, Senior Airman Connor, whose full name was withheld for security reasons, said he had “probably like a 3-by-2 foot space I was in for five hours.”

But there’s still room for a keepsake or two, which for some Airmen play as vital a role as their helmets and exposure suits. Nance carried a medallion his uncle gave him when he first got his flight wings—and a pencil-shaped tire pressure gauge tucked into the sleeve of his flight suit.

“When I was a brand-new lieutenant, a bunch of guys talked me into buying a Harley, and they convinced me that I had to be checking the tire pressure all the time,” he said. “They were messing with me, but in 2009 I was deployed, and we almost had a midair [collision] with a Marine CH-53 [helicopter]. Our aircraft commander saved our lives, but my tire pressure gauge disappeared. After that I never flew without it.”

Flying the lead helicopter, Capt. Parker Imrie carried a challenge coin from the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, the unit his late brother served with in Afghanistan. In the back of the helicopter, Williamse, the SMA, carried a fish keychain his wife gave him years ago that he’s kept in his bag ever since.

Into the Blue

The rescue package flew over the Pacific at about 5,000 feet, with broken clouds ahead and the marine layer—a low expanse of cloud and fog—below.

“The question is, does this marine layer go 10 miles out or 1,000 miles out,” Imrie said. “You don’t know until you fly out there.”

Eventually, the helicopters had to gas up: a delicate operation where the helicopter pilot has to match the C-130’s speed and altitude while the gas flows, then back out slowly without yanking off the hose.

“If all the conditions are right, it’s not that hard. It’s just kind of a little video game: line up and plug in,” Imrie said. “But as you add weather, turbulence, fatigue, poor visibility, or having to plug on the right side of the aircraft, where you get a lot more turbulence coming off the wing, that difficulty ticks up very quickly.”

Staying calm is also key: the pilot might wiggle his or her fingers to avoid white-knuckling the stick, while the crew keeps their voices steady, almost a monotone.

“If one person starts getting tense and has an elevated voice, then everybody hears it, pilots will start gripping it tighter,” Williamse said. “Even for me in the back when I’m doing a hoist, if my voice is super fast and loud, you can feel it in the hover.”

“There’s a psychology to flying a helicopter with four people,” Imrie added.

Indeed, much like how the pilots routinely check their instruments to see how the aircraft is doing, the crew keeps up a low level of conversation during the long hours over water.

“There definitely were periods where everyone was silent for a while, which is OK,” Imrie said. “But you don’t want to let that go on for too long, because you don’t know: Is this guy just silent because he doesn’t have anything to say, or did he fall asleep, or is he having a medical emergency?”

On the other helicopter, Connor the PJ enjoyed listening to the banter, but he and Tech. Sgt. Sean, the more experienced PJ on board, had to conserve their mental energy for later.

“We just tried to relax, knowing that the next six, seven hours were going to be pretty exhausting,” Connor said.

Contact

Nance’s C-130 raced ahead to contact the Port Kyushu. The Airmen were not 100 percent certain if the ship captain spoke Russian, and now it was time to find out.

“Initially it was just one of the crew members and I said, ‘Do you speak Russian?’ And this guy went into a full-blown conversation in Romanian,” said Scheglov. “I don’t speak Romanian, it’s a totally different language. I’m like, ‘Oh good Lord, I just made this whole flight for nothing.’”

But the crew member eventually got the captain on the radio and yes, he spoke Russian. Scheglov told the captain how to prepare for the rescue, which saved precious time when the HH-60s arrived 45 minutes later.

“The ship was positioned and ready to go, the patient was packaged and ready,” Nance said. “We went from what potentially could have been an hour on scene to, like, under 30 minutes.”

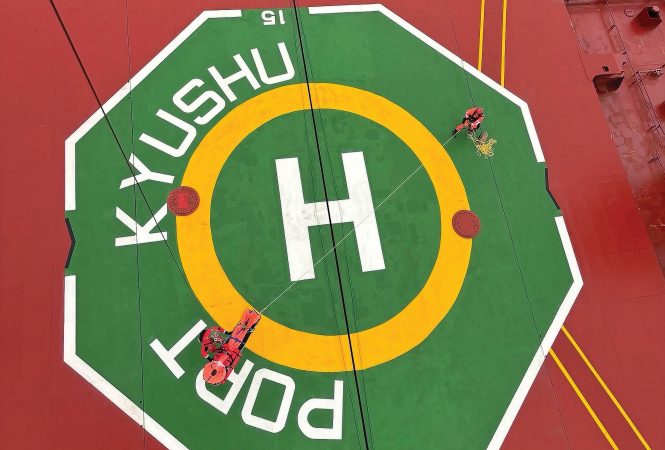

The seas were calm that day, but it would be a long hoist ride down to the Kyushu for the two PJs aboard the pickup helicopter. The HH-60 hovered about 100 feet above the ship to avoid the cranes on either side of its small helipad—too small for the HH-60s to land.

Hoist work is a delicate balance for SMAs, said Williamse, who was on the other HH-60 that day. SMAs have to keep an eye on the person being hoisted, on the steel cable connecting them to the helicopter, and on their surroundings.

Hoisting too fast might hurt the person being hoisted, but going too slow extends the vulnerability period. Too much slack can weaken the cable or get it wrapped around a body part or an obstacle; too little makes it tough for the person to unhook, and if the helicopter moves then it could throw them into the ship’s rail and over the side.

“You keep that fine line of cable slack while also scanning around the aircraft, staying calm, and talking to your pilots,” he said. “I like to say you’re Bob Ross in the back, painting a picture.”

The crew of the Port Kyushu were fascinated; after all, two helicopters had just appeared over the middle of the Pacific and dropped two men in bright red anti-exposure suits on their deck.

“You could see them just kind of stunned at what was going on,” Connor said.

Once on the deck, Connor and Sean met the captain, assessed the unconscious patient, then packaged him onto a litter. With no easy way of carrying him onto the helipad, the Airmen pantomimed instructions for the crew to form a kind of train.

“That was one of the coolest moments, working with this crew that didn’t speak English to get their friend and crewmate where he needed to go,” Connor said. “There was no translation, but everybody understood.”

Once the patient was on the helipad, the PJs radioed the helicopters for a pickup.

“This is where you see the skill of the 129th, because everybody is working together here,” Connor said. “The pilots are dealing with a small area to get the hook in place: They are dealing with the ship cranes, so they can’t just come in from any angle. They are dealing with the movement of the ship. But they come in and drop the hook basically right in our hand. That just comes from practice.”

The PJs did forget one thing: a Port Kyushu life buoy to commemorate the rescue.

“We were so focused that that slipped our mind,” Connor said. “The PJs watching us from the other helicopter saw us coming up and they were like ‘they didn’t get the life ring.’ They realized it before we did.”

The Way Back

The first hour of the flight back was an intense one for the PJs, who had to reassess the patient, hook him up to their monitors, put him on oxygen, and get an IV in: a tough task with a cold, severely dehydrated patient on a loud, moving helicopter. The PJs kept an eye on his vitals, but he remained stable and unconscious throughout the flight. It just wasn’t clear what had endangered his life in the first place.

“It could have been many different things, but there was no definitive sign telling us what exactly was wrong,” Connor said.

Throughout the flight, the medics were in close contact with doctors back home, but they too were stumped. Day turned to night as the helicopters flew about 300 feet off the water for much of the way back, staying low to ensure the patient breathed in as much oxygen as possible. It wasn’t until about halfway through the return flight that Connor had a chance to think about anything else.

“That’s a big moment, when you have five minutes to sit back and take care of yourself,” he said.

This was Connor’s first rescue as a fully mission-qualified PJ after shadowing a few previous ones and graduating the 2.5-year training pipeline just five months earlier. But the Kyushu job felt like any other practice run.

“At no point did I feel like I was doing anything that I had never done before or that was out of the norm,” he said. “It all felt very calm.”

The anti-exposure suits grew pungent in the night air, especially when the PJs asked the pilots to turn up the heat to keep the patient warm. At least the PJs could move around a little, while the helicopter pilots were bound to their seats throughout the journey.

“The biggest surprise for me was that my [tail] didn’t hurt,” said Imrie. “I’ve flown three-, four-, five-hour training sorties where I can barely walk afterward. And then this was the longest continuous flight I’ve ever done, nine and a half hours, and I was definitely ready to not be sitting any more, but it was fine.”

Back in the cabin, Williamse’s knees and lower back grew sore from spending all day crouching and hunched over.

“I was doing all sorts of stretches,” he said. “That is one plus side of being in the back.”

Nance’s C-130 landed at Moffett Field a little after 9 p.m., about 10 hours after it had first taken off, while the HH-60s followed about 15 minutes behind. The helicopters could have flown to Stanford Hospital, but the wing decided it would not be worth the additional risk after such a long flight. Instead, Connor and Sean hopped into an ambulance for the 25-minute drive.

“We wanted to be able to give a handoff at the hospital,” Connor said. “We walked into the ER in our dry suits with 30 people waiting for us.”

Back at base, the aircrews debriefed, then the helicopter crews reconvened at their squadron heritage room, a lounge adorned with thank-you notes from old rescues, photos of past deployments, and totemic depictions of the “Jolly Green Giant,” a symbol of Air Force search and rescue dating back to the Vietnam War.

“Even though you’ve been flying for hours, when you finally get back you can’t just go home and go to sleep, because you still have a sense of adrenaline,” Williamse explained. “So we usually come in here, chill out, drink a beer or two, and relax until you start getting tired.”

About two weeks after he got picked up, the patient was on the mend.

“When I heard that the patient was talking again, was back to normal, it made everything that I’d gone through to get to that point feel very worth it,” Connor said. “I’m fully confident that any one of the new PJs that I just graduated with could have done that exact mission. But I’m grateful that I’m on this team and was given that opportunity.”

And Scheglov? He ended the day with a keepsake of his own, though it requires explanation. The shoulder patch for the 130th Rescue Squadron, the unit which flies the HC-130J, depicts a shark biting into an aerial refueling hose—a twist on the emblem of the San Jose Sharks, the nearby professional hockey team.

Airmen at the 130th wear a version of the patch with a baby shark on it until their first rescue mission or deployment, after which they wear the grown-up shark version. Thanks to his vital translation work, Scheglov got the grown-up shark, making him an honorary 130th member.

“I’ll wear it with pride,” he said.

A month later, the wing was back at it, rescuing a 79-year-old fisherman with stroke-like symptoms about 400 miles off the coast of San Diego. This time they got the life buoy.