When Steven Bennett made his decision, he was well aware

that no pilot had ever ditched an OV-10 and survived.

In the spring of 1972, the United States was well along on its withdrawal from the Vietnam War. Only one large Army unit was still there, and it was getting ready to go home. Remaining U.S. strength consisted mostly of Air Force and Navy airpower and a dozen U.S. naval vessels in the Tonkin Gulf.

North Vietnam saw an opportunity and made a radical change in strategy, departing from its customary insurgency-style warfare to instigate a major conventional operation, the “Easter Offensive.” The main fork of it pushed directly across the Demilitarized Zone into Quang Tri province.

The invaders captured Quang Tri and advanced toward Hue, a strip known to the French in years past as the “Street Without Joy.” American fliers called it “SAM-7 Alley” because of the proliferation of the Soviet-built shoulder-fired missiles. It was deadly, especially against low and slow aircraft.

South Vietnam launched its counteroffensive in June. Late on the second day, June 29, a South Vietnamese platoon was in trouble, under attack by a North Vietnamese force of several hundred.

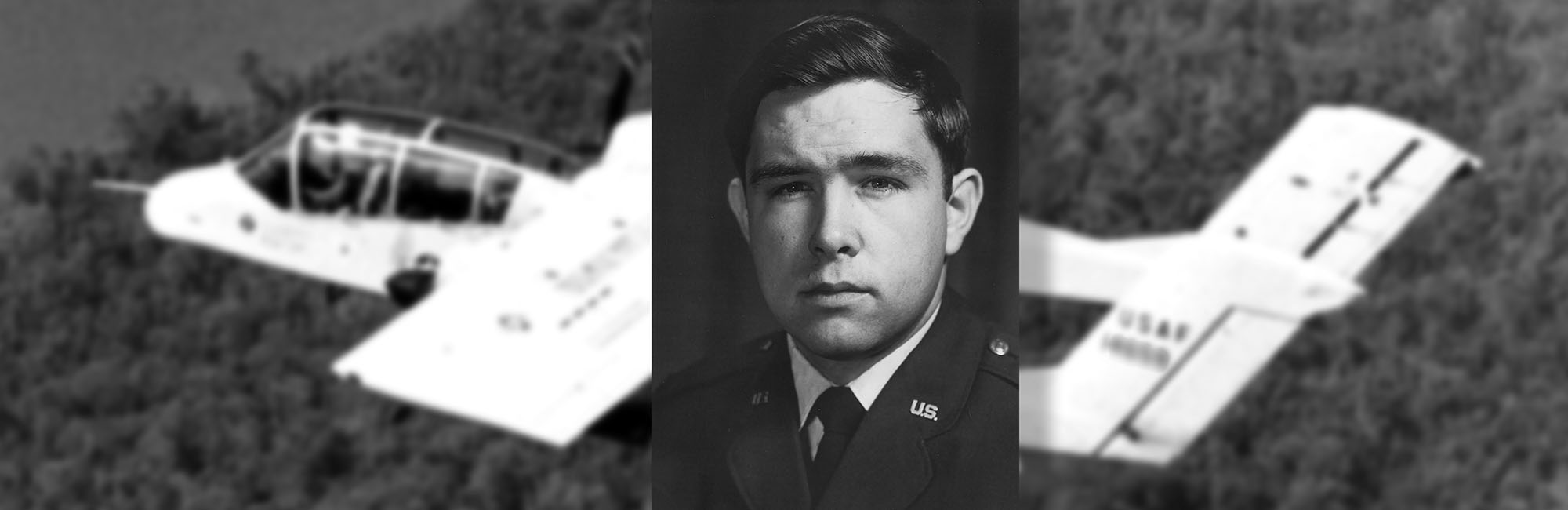

The call for help went to Capt. Steven L. Bennett, 26, a forward air controller flying an OV-10 Bronco out of Da Nang and directing American close air support fighters. Firepower from the U.S. ships in the Gulf was laid by Capt. Mike Brown, a Marine Corps artillery observer in the back seat of the OV-10.

Naval gunfire shoots flat and it has a long spread on impact. There was about a 50-50 chance they’d hit the friendlies.Capt. Mike Brown, a Marine Corps artillery observer in the back seat of the OV-10

No tactical air support was available in time to be of any use. The naval guns were not a solution, either. “The ships were about a mile offshore, and the friendlies were between the bad guys and the ships,” Brown said. “Naval gunfire shoots flat and it has a long spread on impact. There was about a 50-50 chance they’d hit the friendlies.”

Bennett decided to do what he could with his four small 7.62 mm machine guns. The North Vietnamese began to pull back but on Bennett’s fifth pass, a SAM-7 came up from behind, hit the OV-10’s left engine, and tore holes in the canopy. The left landing gear hung down like an injured leg, and the small airplane was afire.

Bennett had to get the airplane to a landing field or he and Brown would have to eject. He fought to drive the airplane up and to the right, but he could not gain altitude. Flying at about 600 feet, he dumped his rocket pods and fuel tank.

The OV-10 was in “command ejection” mode. It could not be reset in the air. Both seats were controlled by the pilot, who would have to punch them out, the back one first.

However, ejection was not an option. Brown had no parachute. It had been shredded by the explosion. Bennett could have ejected alone, but that would have been fatal for Brown when the rocket motors from the front seat passed directly over the rear cockpit.

Momentarily there was hope. The fire subsided and Da Nang was only 25 minutes away. North of Hue the fire fanned up and began spreading. No choice now but to crash-land in the water.

The cockpit area was almost certain to break up on impact. The broad expanse of plexiglass canopy provided excellent visibility but not much structural support. No pilot had ever survived an OV-10 ditching.

The OV-10 dug in hard, cartwheeled, and flipped over on its top, nose down in the water. Submerged, Brown struggled free of his straps, went out the side, and paddled to the surface. He tried to reach Bennett but the airplane was sinking fast. Bennett, trapped in his broken cockpit, sank with it. They recovered his body the next day. He was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously.

Steven Bennett had made his decisions consciously: to press the attack on the North Vietnamese despite the known danger to his small aircraft—and then to ride the crippled aircraft into the sea so that his backseater would have a chance to live, even though it meant leaving almost no chance for himself. He knew the odds. There just wasn’t any other way.