It was the first good war news in months. American B-25s successfully bombed the capital of Japan.

Within days of the disaster at Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the United States began exploring how to retaliate. What followed, unfortunately, was further losses in the Pacific at Wake Island and in the Philippines.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt pressed the armed forces for a bomb strike on the Japanese home islands. Navy aircraft could not do it. Their operating radius was 300 miles and carriers could not get them that close to Japan. Army bombers, on the other hand, had enough range if they flew from a carrier deck.

The Army Air Forces turned to Lt. Col. James H. Doolittle, arguably their best aviator, to work with the Navy on an operation. Doolittle was already famous, having set numerous aeronautical records in years past. He had been recalled to active duty in 1940.

His first task was to choose the airplane. It had to take off within 500 feet and roll down a carrier deck without hitting the superstructure of the ship’s island. The wingspan of the B-23 was too wide. The B-26 takeoff roll was too long.

By default, the choice was the North American B-25, a sturdy medium bomber that carried a crew of five. Doolittle drew airplanes and crews for testing and training from the 17th Bomb Group. The B-25s were stripped of nonessential features and given three extra gas tanks to enable them to fly 2,400 miles, if necessary.

The crews trained in secrecy at Eglin Field, Fla. Only five people knew the full plan—which was for the carriers to launch the bombers some 500 miles from the coast of Japan. The airplanes would then continue on to landing bases in China. There is some question about how much Roosevelt was told.

The Doolittle Raiders and their 16 aircraft put to sea April 2 from San Francisco aboard the Navy’s newest carrier, USS Hornet. They made rendezvous April 13 with the task force that would escort them to the point of launch. The task force was led by Vice Adm. William F. Halsey from his flagship, the carrier Enterprise.

The strike was set for April 18. Doolittle, flying the first B-25, planned to launch that afternoon, be over Tokyo at dusk, and drop incendiary bombs as homing beacons for those coming behind him. Things never got that far. Before sunrise that day, the task force discovered a line of radio-equipped picket boats about 750 miles from the Japanese coast. One of them got off a message: “three enemy carriers.” A cruiser sank the picket boat, but the secret was out. Halsey ordered the bombers to launch at once.

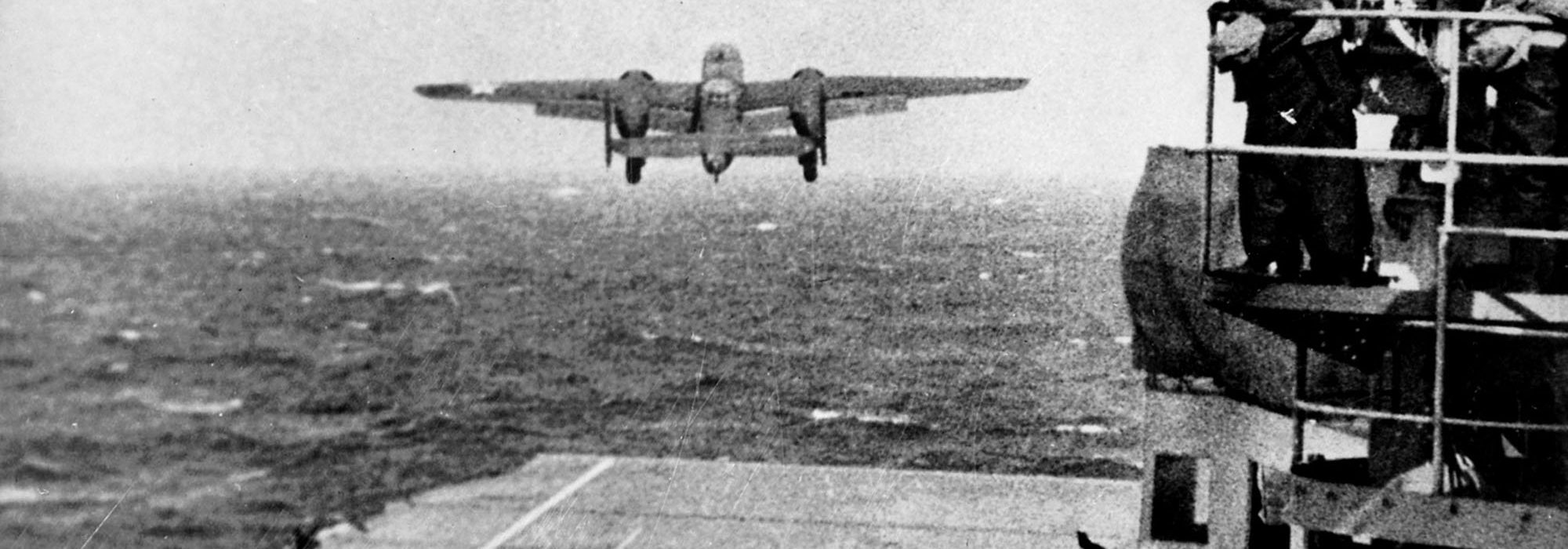

Doolittle took off at 8:20 a.m., clearing the carrier island on his right side by six feet. The others followed rapidly, all of them airborne by 9:19 a.m. Doolittle reached Tokyo and dropped his bombs at 12:25 p.m. Close on his tail came the other Raiders, who struck military targets at Tokyo, Nagoya, Kobe, and Osaka.

The Japanese made no use of the patrol boat warning, mistakenly assuming the carriers to have had only short-range Navy aircraft. They later claimed to have shot down nine of the Raiders. In fact, all 16 bombers got through to land or crash in China or, in one case, divert to the Soviet Union, where the airplane was impounded.

Several raiders were captured by the Japanese in occupied eastern China and executed, but Doolittle and others got back to the United States. Doolittle was promoted to brigadier general—skipping the grade of colonel—while still in China.

The raid is sometimes faulted as unwise because the Japanese inflicted great reprisals on the Chinese. However, fearing more such raids, the Japanese recalled a number of aircraft and ships engaged in their expansion in the Pacific and East Asia and reallocated them to defend the home islands.

News of the raid also had a tremendous uplifting effect on the morale of the American public. Doolittle was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Few of the details were announced. At a press conference, Roosevelt said the bombers had come from “our new secret base at Shangri-La.” Shangri-La was an isolated and mystical valley in Tibet, imagined in a popular novel and movie of the time.

Doolittle’s star continued to rise. More was revealed in “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo,” a book published in 1943 by Capt. Ted W. Lawson, one of the Raider pilots. It was later made into a movie with Spencer Tracy as Doolittle and Van Johnson as Lawson.

By the end of the war, Doolittle was a lieutenant general commanding 8th Air Force in Europe. He returned to civilian life and in 1946 was elected as president of the newly founded Air Force Association. He was advanced to four-star rank on the retired list by Congress in 1985.