Andrews laid the bricks to build an effective (and strategic) air arm.

Frank Andrews, generally called “Andy,” was an American Airman who seemed destined for greatness when he died in a plane crash in Iceland in May 1943.

From a patrician Tennessee background, Andrews graduated West Point in 1906 and joined the cavalry. He transferred to the Air Service in 1917 as a major, but stayed in the States during the World War to help organize and administer the rapid buildup of the air arm. After the Armistice, he went to Europe as part of the Occupation Force, and upon returning to the U.S. in 1923, served in various command and staff positions over the next 12 years.

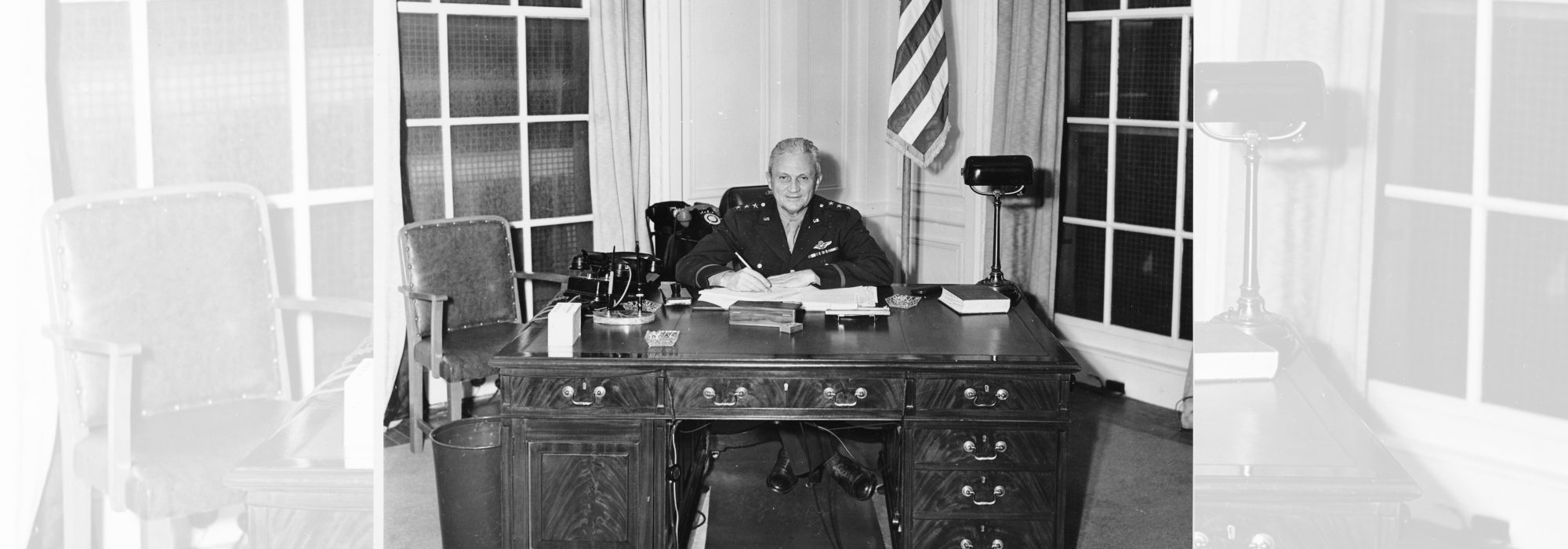

Andrews was generally described as tall, handsome, urbane, and possessed of a calm confidence that made him trusted by those around him. He rose through the ranks as a contemporary of Henry “Hap” Arnold, and although the two held each in mutual respect, they were not great friends. Both, however, believed in airpower and the promise of strategic bombing.

In 1935 Andrews was promoted to brigadier general and given command of the GHQ Air Force. This unit was to be semi-autonomous within the Air Corps and contained most of its combat aircraft. Andrews was soon promoted to temporary major general, the same rank as the Chief of the Air Corps, Oscar Westover. Their relationship was rocky because although Andrews controlled the operational assets of the Air Corps, he was dependent on the supply, logistics, and personnel assets controlled by Westover. It was a confused chain of command.

During peacetime, the GHQ Air Force served under the Army Chief of Staff; in time of war it would work for the theater commander. Allowed to buy 13 of the new B-17s as test aircraft—but only 13—the GHQ Air Force used them extensively in wargames, exercises, and long-distance flights to demonstrate their range, capability, and potential. Andrews became an outspoken advocate for airpower and the need to put the B-17 into mass production. The General Staff instead bought medium bombers, like the B-18, because they were cheaper.

In September 1938, Westover died in a plane crash, and Andrews was a prime candidate to take his place. When interviewed for the job by the Army Chief of Staff, Gen. Malin Craig, Andrews was pointedly asked if he would stop lobbying for more big bombers if he became Chief of the Air Corps. He said no. He did not get the top job, but was instead sent to Fort Sam Houston in Texas to be the air officer for the VIII Corps. He reverted to his permanent rank of colonel. It was hardly a coincidence that this was the same job and the same office to which Billy Mitchell had been exiled when he took on the General Staff 14 years earlier.

Fortunately for the country, a few months later the new Army Chief, Gen. George C. Marshall, brought Andrews to Washington, promoted him back to brigadier general, and made him his deputy chief of staff for plans and operations. This was the most important position on the General Staff, and Andrews was the first Airman to hold it. There he began preparing the Army for the war that all sensed was coming. He pushed immediately and relentlessly for two weapons the General Staff had steadfastly resisted up till then—the tank and the airplane.

After Pearl Harbor, Andrews, now a lieutenant general, was made commander of the Caribbean Defense Command. Another first for an Airman, Andrews as a joint theater commander was responsible for the safety and defense of the Panama Canal.

Two more theater commands would follow over the next year: first was the Mediterranean and then in January 1943 he took over the European theater where he was responsible for the buildup of the Operation Overlord invasion forces.

On May 3, 1943, Andrews boarded a B-24 bound for the States. En route when attempting to land in bad weather at Keflavik, Iceland, the plane hit a mountain, killing Andrews and all but the tail gunner. It has been a matter of endless speculation as to why he was flying back to the States. There are no clear answers. Some speculate that he was to be offered command for the Overlord invasion, but most see that as unlikely—he had not yet held a combat command despite his high rank. Marshall later said that he had been grooming Andrews for great things; hence, his positions at G-3 and theater commands where he worked with not only the Army and Navy, but also the British. Unfortunately, Marshall never elaborated.

Andrews died when he appeared to be on the cusp of greatness. It has been difficult to write his biography because he left behind few papers. There have been articles and book chapters here and there, but finally there is an excellent biography by Kathy Wilson, “Marshall’s Great Captain: Lieutenant General Frank Andrews” (University Press of Kentucky, 2024).