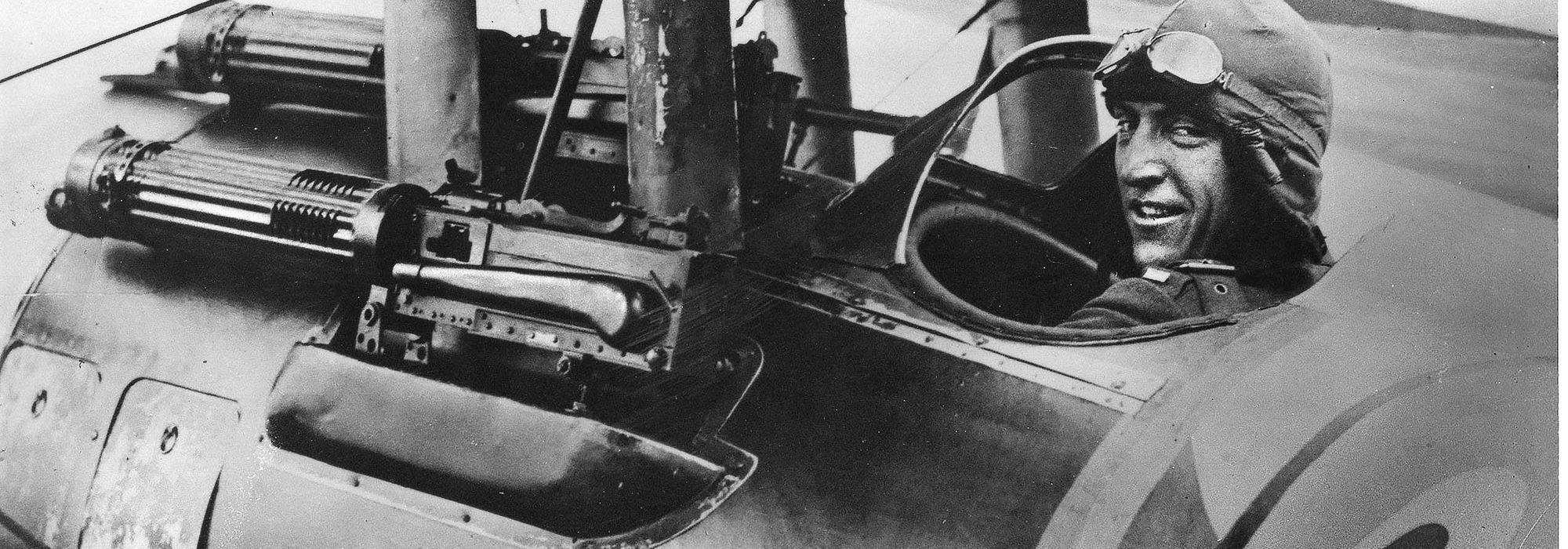

America’s first great Ace was 27 when he earned his wings.

E

dward Vernon Rickenbacker, or “Captain Eddie” to many, was America’s “Ace of Aces” in World War I. In a scant six months, he shot down 26 German aircraft and balloons. He earned a Medal of Honor for those heroic exploits, and photos from the period invariably show him in uniform standing next to his Spad. But Rickenbacker led a full life with many other important accomplishments to his credit.

Born to German immigrant parents, Eddie’s father died when he was just 14, making a hard life even harder. Forsaking school, Rickenbacker worked a variety of jobs, mostly hard, grinding manual labor in a glass factory, foundry, brewery, shoe factory, rail yard, and an automobile garage. Yet despite his lack of a formal education, he had a curious mind and a knack for understanding and using technology. He became an excellent auto mechanic, but he enjoyed driving the cars he worked on even more. By 1914, he was an auto racer with a national reputation.

When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, Rickenbacker suggested that the Air Service invite race car drivers to form a pursuit, or fighter squadron. Auto racing had natural similarities to flying, demanding quick reflexes, mechanical acumen—and guts. The Army, however, dismissed the suggestion, then drafted him anyway. Because of his racing background, Rickenbacker became Gen. John Pershing’s driver, and then Billy Mitchell’s, whom he badgered until Mitchell finally agreed to send him to flying training. At at age 27, Rickenbacker had been considered too old for such duty, but now he had his chance, and upon becoming a pilot he was posted to the 94th Aero Squadron—whose famous logo was Uncle Sam’s hat inside a ring. Thus began his career as America’s greatest fighter pilot of the war.

Rickenbacker was a fearless and aggressive hunter. He would never admit defeat and rejected any attempts at sentimentality. His job was to kill Germans. One reason for his success was the interest he took in the workings of his machine, personally checking his aircraft, engine, guns, and even the bullets—before and after each flight.

Rickenbacker returned from the war a hero. America was at his feet, but after a few wild years, he realized it was time to get back to business. He started his own car company and then bought the Indianapolis 500 Racetrack and rebuilt it—making it the premier racetrack in the world. With backing from General Motors, he moved into the airline business and bought Eastern Airlines, making it a great success.

When World War II broke out, Rickenbacker was eager to serve his country once again. He was rabidly anti-Roosevelt, however, so attempts by Gen. Henry H. “Hap” Arnold to put him to work in the Army Air Forces were thwarted, at least at first. Eventually, he was allowed to tour the country and give pep talks to fighter pilots going overseas, a role in which he proved inspirational. FDR then decided to give him a more serious task: He was to visit Gen. Douglas MacArthur—then in New Guinea—and deliver a secret message from the President.

En route to New Guinea, the B-17 on which Rickenbacker was a passenger got lost, ran out of fuel, and ditched at sea. For 24 days, Rickenbacker and seven others bobbed in rubber life rafts. One died, and as the others slowly wasted away, Rickenbacker prodded them to stay alive—it was all too easy to merely quit. When they were finally rescued, the others admitted they survived only because of Rickenbacker. After convalescing for two weeks, Rickenbacker flew on to Port Moresby and delivered his message to MacArthur. Neither ever revealed the content of the secret message.

After the war Rickenbacker continued to run Eastern Airlines, but poor business decisions eventually put the company into a slow decline. When Rickenbacker retired in 1963 at age 73, Eastern was still afloat, but clouds were on the horizon.

For the next decade Captain Eddie worked on his memoirs and spoke out about the dangers of communism and the importance of never giving up. On vacation to Europe in 1973, Rickenbacker died.

Rickenbacker moved from one challenge to the next throughout his life and succeeded at every stage, thanks to his indomitable will, aggressiveness, fearlessness, and determination. Never formally educated nor gifted with exceptional intelligence, he knew his limitations and drove himself relentlessly to overcome them.

Rickenbacker wrote two memoirs: Fighting the Flying Circus (Stokes, 1919) and Rickenbacker (Prentice-Hall, 1967). A fictional biography, Fast Eddie, by Robert O’Connell (William Morrow, 1999), is a terrific read.