Career Airman who served proudly.

Our armed forces have not always been integrated. Although Blacks served, they did so in specialized units commanded by White officers and suffered institutional discrimination in the 1940s and beyond. Racial inequality was both pervasive and humiliating.

Benjamin O. Davis Jr. understood the problem. His father, Benjamin Davis Sr., was an Army officer who had entered service during the Spanish-American War, saw action in World War I, and was then posted to teaching positions at Black universities—the Army did not want him in command of White soldiers. He became a brigade commander of an all-Black cavalry unit in 1937, and in 1940 was promoted to brigadier general—the first Black general in American history.

Ben Davis Jr. was likewise attracted to the military, and after two years of college was appointed to West Point. He graduated in 1936, the first Black to graduate since 1889. His treatment while a cadet was poor. White Soldiers and cadets did not want Blacks at their Academy, and tried to drive Davis out. He was silenced: No one, not fellow cadets, not instructors, and not the staff, was permitted to talk to him, except in the line of duty, for his entire four years. He roomed alone; he ate alone; he studied alone. But Davis was stubborn and refused to break. He later stated that only the unending support of his girlfriend, Agatha Scott, who visited him most weekends, got him through the ordeal. It is telling that it was over 50 years before Davis returned to his alma mater. He had no fond memories.

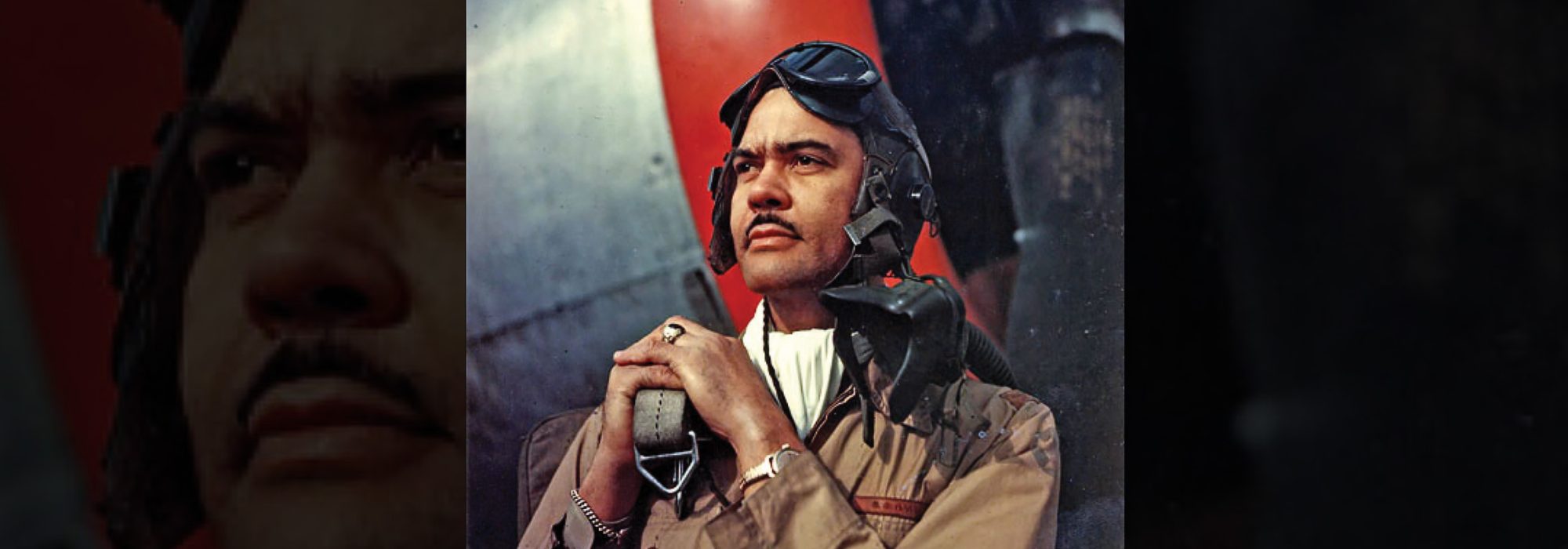

He and Agatha married after graduation and Davis applied for pilot training but was refused. There were no Blacks in the Air Corps. He was instead given infantry assignments in Black units where he did not interact with Whites. Rapid change occurred when war broke out in Europe and it was apparent the U.S. would soon get involved. In 1942 Davis finally became a pilot. When the 99th Fighter Squadron was formed with only Black pilots who had attended the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, Lt. Col. Davis was named its commander.

Davis took his squadron to North Africa where its P-40s flew ground support and escort missions. Despite the unit’s obvious abilities and statistical achievements, the Tuskegee Airmen were still not treated as equals. Its officers, contrary to Army regulations, were not allowed to use the Officers Club—Whites did not want them. After a tour in Washington, D.C., Davis returned to Europe as a group commander—again commanding the Red Tails. The mission of the group, now flying P-51s, was escort for the bombers of the Fifteenth Air Force. Their performance was outstanding and everyone soon realized it, and they finally earned a measure of acceptance and respect.

In 1948, President Harry Truman issued an executive order decreeing integration of the military. Davis attended Air War College, and he later wrote that this was the first time he had the chance “to associate with my White peers.” He moved to the Pentagon as head of the Fighter Branch and in that position pushed for the fighter force to be air refuelable and for the establishment of an elite aerial demonstration team—the Thunderbirds.

He was a fighter wing commander in the Korean War, and received his first star in 1954 as chief of staff of Twelfth Air Force. He returned to the Pentagon where he pinned on a second star—the first Black officer to reach that rank in American military history.

During the Vietnam War, Davis was again sent overseas—his third war and now wearing his third star. As commander of the Thirteenth Air Force in the Philippines, he was responsible for a key unit flying daily combat missions in Southeast Asia. It was a job that also involved much diplomacy as he traveled throughout the theater meeting with allied military and civilian leaders. He returned from the war to become deputy commander of Strike Command.

Davis retired in 1970, but President Richard Nixon soon named him the director of civil aviation security for the Department of Transportation at a time when aerial hijackings were increasingly common. He moved quickly to counter this threat. He retired again but stayed active in various civic and veterans’ groups.

In 1998, Congress approved his promotion to four-star general and President Bill Clinton pinned on his fourth star. Davis lost his beloved Agatha in 2002, and he followed her soon after.

Benjamin Davis Jr., was a true American hero who served his country through three wars, despite facing countless obstacles along the way. He never quit; he simply worked harder.

“Benjamin O. Davis Jr., American” is the title of the general’s memoirs and they are insightful, honest, and sobering. A good biography is needed of this important American Airman.