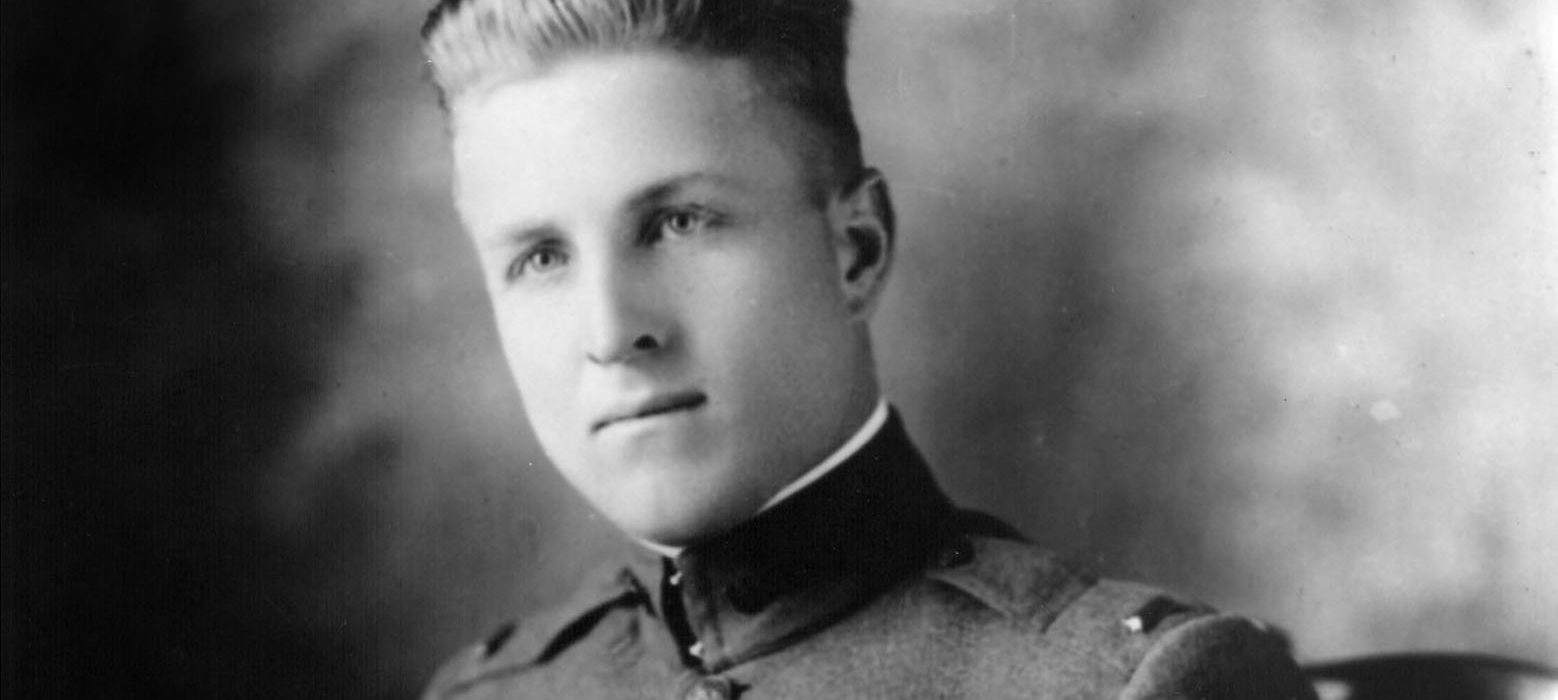

Frank Luke shot down 18 enemy aircraft

in his 18-day combat run in World War I.

This story was originally published June 30, 2021.

The Air Force has never seen anything, before or since, to match the relentless offensive of Frank Luke, who shot down 14 German balloons and four German airplanes in 18 days in September 1918.

He was the first Airman ever awarded the Medal of Honor and the second-ranking US ace of World War I. Eddie Rickenbacker, the leading ace, declared Luke to be “the most daring aviator and greatest fighter pilot of the entire war.”

Luke did not live to see the armistice, which brought the war to an end three months after his final mission on Sept. 29, 1918, from which he did not return. Nothing was known of his whereabouts for months and conjecture surrounds what happened on that last day.

He did not fit the mold of U.S. air heroes, typically team players, supportive, and modest about their own achievements. Luke, 21, was arrogant, boastful, self-centered, and undisciplined. He made few friends.

His fearlessness was not “courage, exactly,” said Lt. Jerry Vasconcells, who served with him. “He can’t imagine anything happening to him. He thinks he’s invincible,” and “he may be almost as good as he thinks he is.”

In August 1918, his unit, the 27th Aero Squadron, redeployed to Rembercourt near Verdun to be closer to the fighting in France. It was equipped with the Spad XIII, the best Allied fighter of the war and a match for the best German fighter, the Fokker D. VII.

Luke shot down a German observation balloon, his first aerial victory, on Sept. 12. The big sausage-shaped Drachen were used to correct artillery fire. Attacking them may sound like shooting fish in a barrel but it was more difficult and dangerous than attacking airplanes. The balloons were strongly defended by anti-aircraft cannons, machine guns, and infantry small arms.

Col. Billy Mitchell, commander of Air Service combat forces, ordered pursuit squadrons to destroy the balloons if they could. Luke was determined to roll up his score, and do it his way—which meant flying with or without orders, often without filing a flight plan. On five occasions, Luke returned with so much battle damage that he had to use a new airplane for the next mission.

Luke’s biggest day was Sept. 18, when he had five victories: two balloons, two Fokkers, and a German observation plane. With 13 confirmed victories, he became front-page news in The New York Times and even more difficult for his squadron commander to control. Nobody wanted to diminish the reputation of a new celebrity who was delivering on Mitchell’s directive.

On Sept. 29, Luke took off around 6 p.m., alone and without permission, for what would be his last mission. As he passed over Avocourt, he dropped a message, weighted with a piece of metal, saying, “Watch for burning balloons.” Nothing further was heard from him, and he was declared missing in action.

In January 1919, a Graves Registration Unit found Luke’s remains at Murvaux, a small town east of the Meuse. A U.S. Army officer, who spoke no French, understood local residents to say Luke had shot down another balloon, then was shot down himself, after which he used two pistols to kill seven German soldiers before being killed himself. He was awarded the Medal of Honor in May.

The story was embellished over time. One version had Luke killing 11 Germans in an epic gun battle. An article in Air Force Magazine in 1955 claimed that Luke had been attacked by 10 Fokkers, which he fought “for a full five minutes,” shooting down two of them.

A credible version of the final flight did not emerge until historian Stephen Skinner reported in 2008 on his deep research into contemporary records and other original sources.

It was still daylight when Luke approached Murvaux, which lay in a valley. A high hill on the north side bristled with German machine guns. Luke came in from the north, using the hill as a screen, but when he turned up the valley to attack the balloons, the guns opened up on him from above.

He was hit and mortally wounded in the air. He landed his Spad in the valley, climbed out, and collapsed 221 yards from the airplane. He had one sidearm, a 1911 Colt semiautomatic with seven rounds left in the clip. He probably fired three shots. It is possible, but not likely, that the Germans returned fire.

Luke’s advantage in his two-and-a-half-week combat run was his special combination of courage and flying ability. That was enough to put him in a class by himself as a fighting Airman.