Pitsenbarger chose to remain under enemy fire to care for and help defend the wounded.

In the early afternoon of April 11, 1966, Charlie Company, an element of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division, flushed a Viet Cong (VC) platoon, killed several of the VC, and pursued the others deeper into the dense jungle east of Saigon.

The Americans had no idea they were walking straight into the base camp of the Viet Cong battalion known as D-800, a first-line unit with 400 troops, plus available backup. Charlie Company, with a strength of 134, was soon isolated and encircled.

The fighting grew desperate. Before it was over, all but 28 of the U.S. troops would be wounded or killed. The triple-canopy jungle was too thick for Huey reinforcement helicopters to land, but there was a gap nearby just wide enough to lower a litter on a hoist line 100 feet to the ground.

Two Air Force HH-43 Pedro rescue helicopters were dispatched from their base at Bien Hoa in Vietnam to pick up the wounded. The first extractions were awkward. The Army was unfamiliar with rigging the equipment, and the litters snagged repeatedly in the trees. The Pedros had no direct contact with the soldiers.

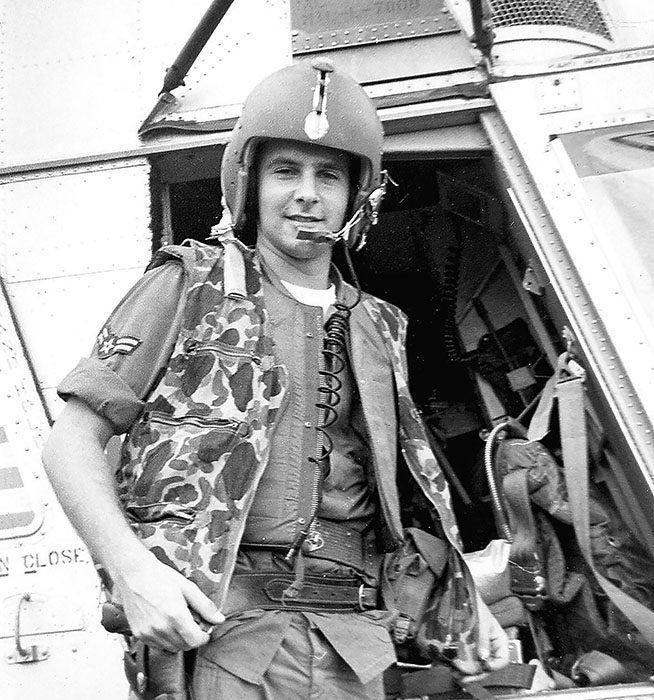

One of the pararescue jumper medics—popularly known as PJs—was A1C William H. Pitsenbarger , 21. He had been in Vietnam for eight months and had been awarded the Airman’s Medal for bringing a wounded Vietnamese soldier up from a burning minefield.

Pitsenbarger convinced his HH-43 pilot to put him on the ground with Charlie Company and leave him there to prepare the litters and hoist and to coordinate the extractions. He went down on the forest penetrator, holding his medical kit, his M-16 rifle, and an armful of splints.

“At times the small-arms fire would be so intense it was deafening and all a person could do was get as close to the ground as possible and pray,” said Lt. Martin Kroah, leader of one of the Army platoons. “It was on these occasions that I saw Airman Pitsenbarger moving around and pulling wounded men out of the line of fire and bandaging their wounds. My own platoon medic, who was later killed, was totally ineffective. He was frozen with fear, unable to move.”

The HH-43s had picked up nine wounded soldiers when one of them was hard hit by automatic weapons fire. The crew cut loose the dangling litter and the helicopter managed to limp—out of commission—to a landing field. Ground control told the other Pedro that with the area under such intensive attack, no more extractions could be attempted that day.

Pitsenbarger gave his handgun to one of the wounded who could not hold a rifle and ran from place to place, gathering ammunition from the dead and taking it to those who were running short. “Pitsenbarger continued cutting pant legs, shirts, pulling off boots, and generally taking care of the wounded,” said Army Sgt. Charles F. Navarro. “At the same time, he amazingly proceeded to return enemy fire whenever he could. During his movement around our perimeter, he would scramble past me and deliver a handful of magazines.”

The VC stepped up the attack in the late afternoon. Snipers in trees shot soldiers in the back as they lay prone in the firing position.

Pitsenbarger was shot four times. Struck in the back, shoulder, and thigh, he kept working and fighting until the fatal round struck him in the head. He died about 7:30 p.m.

The enemy mounted three massive assaults around the perimeter. Charlie Company survived the night only by calling in artillery almost on top of itself. Reinforcements finally broke through at dawn.

The commander of the Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Group nominated Pitsenbarger for the Medal of Honor, but the recommendation was marked down to an Air Force Cross by Military Assistance Command Vietnam.

More than 30 years passed before a group of Pitsenbarger supporters were able to get his case reopened. “I felt at the time, and still do, that Bill Pitsenbarger was one of the bravest men I have ever known,” said former Army Lt. Johnny Libs, one of the surviving platoon leaders.

With strong backing from the Air Force and concurrence of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Pitsenbarger was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. His father accepted the award Dec. 8, 2000, on his behalf.