Combat airpower requires more planes and more pilots to fly them.

The U.S. Air Force is stretched thin by unrelenting rotational and contingency response demands, and its chronic pilot shortage just won’t go away. For more than a decade, the Air Force has fallen short of its pilot goals by about 2,000—the number was about 1,850 pilots in 2024—and with aging combat aircraft inventories, more planned force structure divestments, and projected squadron closures complicating the problem, the service is now struggling to ensure its pilots have the experience needed to succeed in combat. The Air Force no longer has the depth of forces—neither aircraft nor pilots—needed to withstand combat losses and sustain effective combat operations at the scale, scope, and speed necessary to prevail against a peer adversary.

Growing the Air Force’s corps of seasoned pilots who can survive and be mission-effective in a highly contested battlespace is crucial to being able to successfully employ air combat capabilities across the range of conflict in any theater around the globe. That will require not only new pilots, but the ability to retain those already trained and skilled.

During the Cold War, when the United States last confronted a peer adversary, the Air Force possessed 422 bomber and well over 4,000 fighter aircraft. Today, with a more complex array of peer threats around the globe, the U.S. Air Force’s combat aircraft inventory is the smallest in its history: 142 bombers and just over 2,000 fighter aircraft. The bomber fleet averages nearly 50 years of age; the fighters, about 30. Age correlates with readiness, as planes need more maintenance as they get older, reducing their availability. In fiscal 2024, mission-capable rates for bombers were just over 50 percent; for fighters, mission capable rates—which measure an aircraft’s readiness to perform at least one of its assigned missions—ranged from 40 percent for F-22s to 64 percent for F-16s. Overall, mission capable rates for fighters averaged less than 58 percent.

With so many combat aircraft well past their service design life, and most lacking the stealth and other attributes and capabilities necessary for peer-level conflicts, America faces a crisis in airpower.

To reverse the downward spiral, meet current peacetime rotational and training demands and be ready to fight and prevail in a complex and protracted peer conflict, the Air Force must recapitalize and grow its shrinking fleet. It must also grow the pilot corps while retaining experienced pilots—maintaining the right ratios in squadrons and adding strategic depth across the Total Force.

Growing force structure will naturally stress the existing pilot corps. It takes years to build an experienced combat pilot, and the Air Force may not have the time to produce, train, and season new replacement pilots at the pace of need. The Air Force must carefully preserve as much experience as possible in its pilot corps across the Total Force or risk further collapsing the Air Force’s combat readiness. Pilots increasingly voice their frustrations from serving as high-demand, low-density assets. Their continual high operating tempo is driving more and more Air Force pilots to leave the service.

The Active Component (AC) alone cannot meet the service’s mission requirements. The Guard and Reserve are key to retaining and growing a corps of experienced combat pilots to credibly dissuade, deter, compel, and prevail against a peer threat. The Air Force and Congress must commit to the Total Force modernization, growth, and recapitalization necessary to field the force of combat aircraft and experienced combat aviators needed for a high-end fight with a peer competitor. Addressing force size, pilot absorption, and experienced pilot requirements are key to rebuilding a force that wins.

The Experience Imperative

Warfighter experience is essential to prevailing against adversaries—it is often the critical differentiator that can tip operational outcomes in favor of America’s forces in peer conflict, an intangible that cannot be replaced by artificial intelligence (AI) or drones. The term “pilot experience” captures the difficult-to-quantify elements of airmanship, wisdom, judgment, and intuition that can make the difference between winning and losing.

While this experience can be tricky to measure with precision, the evidence of it is not: starting from the World War I, experienced combat pilots have demonstrated superior mission outcomes and lower attrition rates compared to inexperienced pilots. While the introduction of aviation to the Western Front in Europe quickly demonstrated the value of military aviation, the value of experience emerged just as fast. But only by flying at the front could pilots develop the airmanship and judgment needed to survive. New pilots were exceptionally vulnerable their first few sorties, and it took time flying at the front to develop the airmanship and judgment needed to survive. As Allied pilots were lost in combat, replacements arrived with fewer and fewer hours of flight time. By the end of the war, an Allied replacement pilot had a life expectancy of just three weeks once they began combat operations. Some were dead within three days.

In World War II, pilot skill and experience proved even more essential. Moreover, the conflict demonstrated that combat pilot corps must also have sufficient strategic depth or risk collapsing in a protracted conflict. Germany and Japan had skillfully trained their fighter pilots before the war, and they were arguably the best in the world. But the Axis nations were overly optimistic about how long the war would last. Both lacked depth in their pilot corps, and their training pipelines proved insufficient to replace combat losses. Without a sufficient reserve of experienced pilots, a robust training infrastructure and pipeline, or the time to season their pilots, the Luftwaffe and Japanese air forces collapsed under the pressure of U.S. and Allied combat air operations. At the end of WWII, Germany was producing fighters at a rate faster than prewar, but it did not have the pilots to fly and effectively employ them, ceding air superiority completely to the Allies. Japan’s combat pilot corps was similarly devastated, and Japan had little choice but to adopt kamikaze tactics, in which inexperienced pilots were trained to use their aircraft as human-guided missiles.

In contrast, the United States entered World War II with a small and not particularly skilled or experienced pilot corps. Yet the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) and the U.S. Navy benefited from the nation’s rapid mobilization for total war, drawing on the latent capacity of the U.S. civil aviation industry to contract quality pilot training even as they scaled production to expand their pilot corps while replacing pilots lost to combat operations. The number of pilots the United States was able to graduate on a monthly basis during WWII was great enough to prevent its forces from falling into the attrition-experience death spiral that hollowed out the German and Japanese air forces.

Even though training timelines were compressed, U.S. pilots still received 140 hours of flight instruction, enough to impart airmanship, skill, and the initial level of judgment necessary to be prepared for combat. Moreover, the scale of pilot production enabled the USAAF to rotate pilots to nonflying duties or even back to the United States. It became clear that a combat air force must have sufficient experienced pilots to offset combat attrition, provide a reserve of experienced pilots to sustain high-intensity combat operations, and simultaneously surge pilot production. These lessons are relevant today since WWII was the last time the United States fought at a global scale and scope.

The Strategic Depth Imperative

While some might imagine a shrinking aircraft inventory would reduce the pilot crisis, the opposite is true. Fewer cockpits mean fewer sorties, which translates into less pilot training capacity. Divesting aircraft also disrupts the shape of the Air Force’s pilot corps. Crew manning is tied to force structure, and when aircraft fleets are downsized, their pilots must either be retrained or depart the service, and pilot production reduced. In the mid-1990s, as the Air Force drawdown got underway following the fall of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact, the Air Force used all of these approaches, which had the unforeseen consequence of distorting the service’s pilot corps and creating large gaps in pilot experience. The Air Force’s pilot shortage has since only worsened instead of resolving itself—even as the service has continued to shrink its combat aircraft inventories.

The U.S. Air Force must take aggressive action to solve its combat pilot shortfall, but it is not enough to simply produce new pilots at the same rate as seasoned pilots leave during peacetime; the U.S. Air Force must also develop and experience new pilots at the same or greater rate as its losses, especially knowing wartime attrition will drive far higher backfill demands. Because pilots must first fulfill a 10-year Active Duty Service Commitment (ADSC) before they are eligible to exit the service, the pilots leaving are often highly experienced with advanced qualifications as instructor and evaluator pilots.

To grow its combat aircraft inventory and meet required crew ratios, the Air Force must train more than one new pilot for every new aircraft—typically 1.25 pilots per aircraft. Importantly, these additional pilots cannot all be newly trained pilots. As aircraft inventory is added, squadrons must stand up with the appropriate leadership, instructor pilots, evaluator pilots, flight leads, and other supervisors to ensure safe and effective flight operations. Without enough experienced pilots in squadrons, new pilots will not receive the training or supervision needed to become experienced instructors and evaluators themselves at the pace the service needs. Experienced pilots are also crucial across the Air Force enterprise, where their wisdom, leadership, and operational expertise are essential to everything from developing technical requirements and policy guidance to strategy and operational planning. This means that pilot production alone cannot solve the Air Force’s force structure challenges. The Air Force must retain its experienced pilots across the Total Force to field the strategic depth the nation needs.

CCA Can Compliment Human Combat Pilots

Today, the Air Force is aggressively pursuing collaborative combat aircraft (CCA) to boost its combat capacity and fill its combat aircraft shortfalls. These autonomous drones may indeed improve the Air Force’s operational effectiveness by expanding a fighter’s sensor and missile ranges, providing electronic warfare support, acting as communications relays, and otherwise enhancing mission performance. Yet CCA cannot replace human fighter pilots in contested battlespaces because of the fundamental limitations of autonomous technologies. Software engineers unanimously agree that the ability for AI to approach, let alone exceed, a human pilot is still a long way off.

Humans can borrow and apply experiences and insights from seemingly unrelated fields and topics, innovate in relevant ways in real time, take the initiative even when disconnected from external command and control resources, and make decisions in highly uncertain operational conditions. The Air Force should develop CCA and explore their full potential, but they do not negate the need for the proven, reliable, and resilient combat outcomes that only combat pilots can provide. The Air Force must do more to build the strategic depth of combat pilots the nation needs.

The Air Force’s Reserve Component

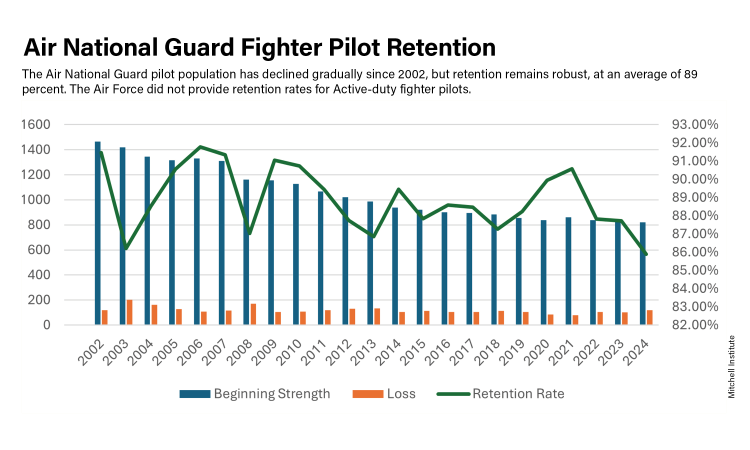

Many qualified, experienced pilots who exit the Air Force’s Active Component choose to continue to serve in the Air National Guard or Air Force Reserve, which together make up the Reserve Component (RC), which boasts a pilot retention rate far greater than that of its Active Component. While the Active Component currently holds a steady retention rate of 45 percent, the Air National Guard has retained an average of 89 percent of its pilots for over 20 years. A robust Reserve Component can ensure that investments made to train and develop mature pilots are retained in the Total Force.

The Reserve Component’s pilot corps predominantly comes from pilots exiting the Active Component at the end of their ADSC, meaning that the Reserve Component has higher percentages of experienced pilots than the Active Component. Many pilots who leave the Active Component seek to join the Guard or Reserve, both of which offer more stability and the opportunity to continue to fly and serve. When coupled with the RC’s retention rate, the strategic depth the Guard and Reserve offer the nation should not be undervalued. The Air Force must acknowledge this reality as it postures to be ready to deter or win a peer conflict.

To further harness this opportunity, the Air Force should increase the number of jets assigned to its Reserve Component fighter squadrons. Reserve Component fighter wing commanders routinely report they must turn away qualified pilots who are exiting the Active Component. These AC pilots clearly want to continue to serve and fly, and growing capacity in the Reserve Component is the only realistic means for ensuring they can do so. Most of the Air Force’s Active Component fighter squadrons have 24 combat-coded aircraft, while its RC fighter units are assigned 18 aircraft. Increasing these RC squadrons to 24 assigned jets would create seven to eight more pilot positions per squadron. These additional aircraft would need associated maintenance support and spares to ensure squadrons can fly them at required rates, but the benefit of retaining more experienced combat pilots would greatly outweigh the costs of these additional resources.

The Air Force’s Active Component must grow to meet operational demands for airpower, and concurrently increasing the service’s RC would help maintain experienced pilots in the force that the Active Component has already developed but cannot fully retain. Taking full advantage of the Reserve Component can greatly reduce the impact of rebuilding a Total Force that is capable of deterring and, if necessary, defeating aggression by a peer adversary. But fighter squadrons in the Reserve Component are at risk of divestiture if they are not rapidly recapitalized with new aircraft, meaning that there might not be anywhere for pilots exiting the Active Component to continue to serve.

Total Force Challenge

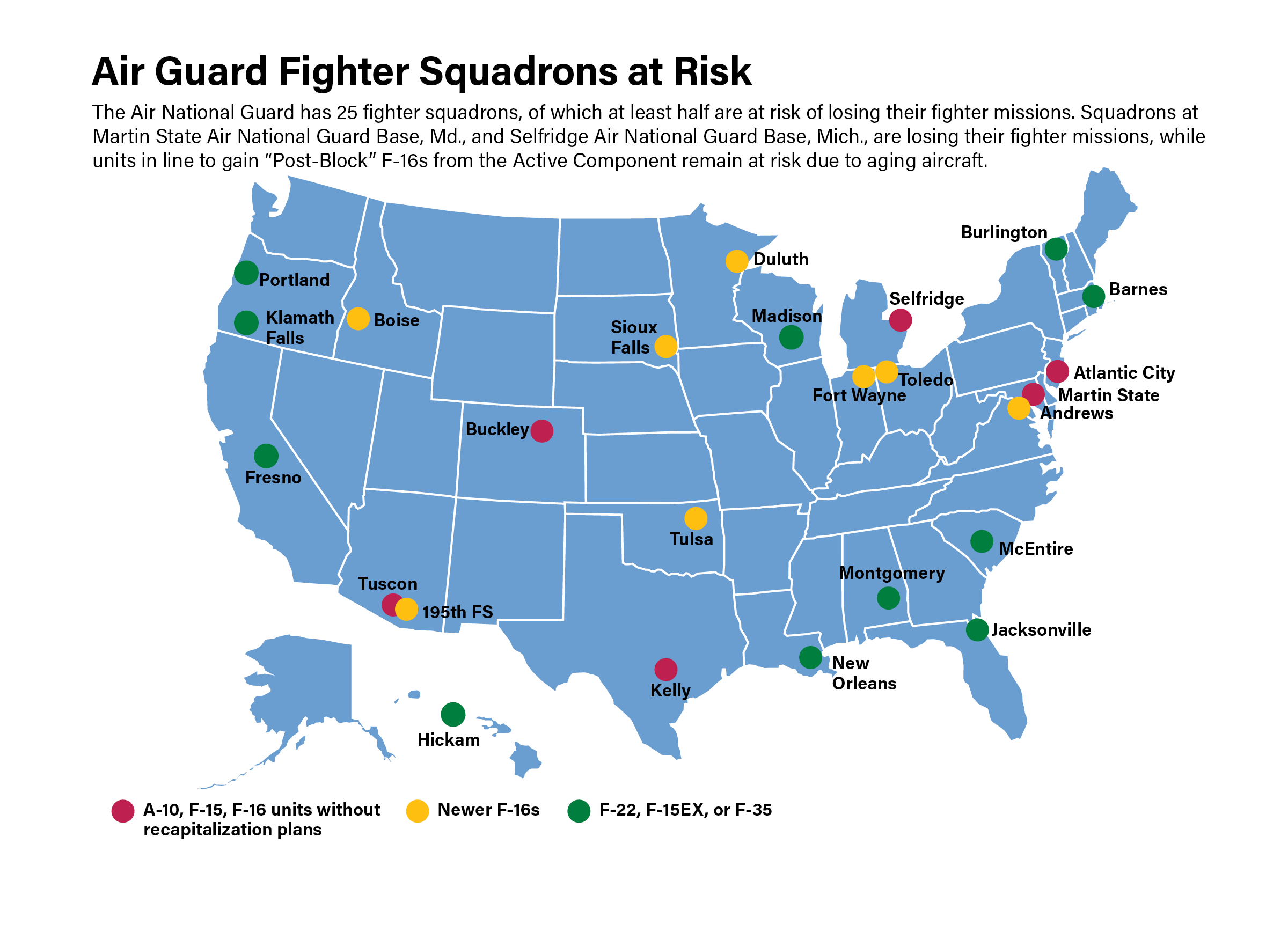

The aging air fleet is worse in the Reserve Component, where F-15Cs, A-10s, and early-block F-16s are among the most likely to be divested. As aircraft recapitalization programs have been terminated, deferred, and slow rolled, the convention of sending older equipment from the AC as it is modernized to the RC is no longer tenable, placing the Reserve Component in distress. Without one-for-one replacement in the near term, divesting more existing aircraft threaten to reduce combat capacity and experienced fighter pilots in Guard and Reserve units.

Indeed, the Air Force plans to inactivate or “re-mission” 13 fighter units across the Total Force. The Reserve Component is at the highest risk of suffering from these types of mission changes. Fleet age is a major factor in these force structure decisions, especially for units with combat aircraft that are at or beyond their planned service life, have structural deficiencies and rapidly growing sustainment costs, and are increasingly difficult to maintain and modernize. While some RC squadrons will recapitalize with new F-35As, many RC fighter squadrons are without a plan to replace their legacy iron.

Shuttering fighter squadrons in the RC will further stress the Active Component, which is already too small. Meanwhile, retiring RC squadrons and divesting their combat capacity will make it harder for the Guard and Reserve to attract and capture those experienced pilots completing their Active Duty Service Commitment.

The U.S. Air Force must recapitalize and modernize its forces as it reoptimizes for great power competition and conflict. As it does so, it should adopt approaches that maintain a robust, experienced corps of combat pilots across its Total Force. Continuing to divest the Reserve Component’s fighter forces will eliminate opportunities to capture pilots departing the AC and retain them in the service—the Air Force cannot afford to lose these pilots entirely. Increasing the Air Force’s long-term pilot absorption capacity and retaining those pilots over their flying life cycle will require recapitalizing and growing the size of its RC and AC concurrently. Recapitalizing and growing both components is the best approach for optimizing the service’s combat pilot experience across the Total Force.

Recommendations

The U.S. Air Force has been studying its pilot absorption and life cycle dynamics for over two decades. Today, the service has better data and models that it can use to understand its pilot ecosystem, but these tools have yet to produce solutions to many of its problems. There comes a point where studies alone will not fix the problem. It takes investment. The Air Force’s pilot shortage has grown even as it cut the size of its forces, increased its pilot retention bonuses, and decreased its pilot staff requirements by opening those positions to its ground specialties, civilians, and contractors. These death spiral patterns must be arrested and reversed.

Decades of chronic underfunding have left the Air Force undersized in comparison to its mission. As Chief of Staff of the Air Force Gen. David Allvin has said, “The nation needs more Air Force.” The Air Force must now grow its combat forces to solve its pilot crisis, and do so in a way that preserves a cadre of experienced pilots. The service should use its pilot life-cycle modeling capabilities to better understand potential unintended consequences and benefits of recapitalizing, modernizing, and growing its force structure. The Air Force should also seek ways to increase the elasticity of its pilot production enterprise to meet changing demand, even if it means reopening pilot training bases. Most importantly, it must grow the size of its Reserve Component combat forces together with its Active Component combat air inventories—it cannot neglect one in favor of the other. The Guard and Reserve are linchpins to resolving the Air Force’s pilot shortfalls because its combat squadrons capture many of the experienced pilots that choose to leave the Active Component. To this end, the Mitchell Institute offers the following recommendations:

1. Grow the Active Component fighter forces to increase the quantity and rate at which it can absorb new pilots and maintain pilot combat readiness. More aircraft would develop the experience new fighter pilots require at a rate that equals or exceeds the pace that its experienced pilots exit the service, while also providing more monthly training sorties for all pilots. Growing the Air Force’s combat aircraft inventory would also decrease the frequency and duration of pilot rotational deployments that have a marked impact on pilot retention.

Replace old aircraft with new at a one-for-one rate. The Air Force’s “divest to invest” strategy for recapitalizing its aging forces is a failure; USAF must immediately stabilize its force size by replacing aircraft at a one-for-one rate. Doing so will also stabilize the Air Force’s fighter pilot corps.

Increase the Air Force’s F-35A acquisition rate. The F-35A is the U.S. Air Force’s primary fighter program, yet procurement rates continue to fall far below the program of record—and, more importantly, USAF’s need. The Air Force should procure 74 F-35s per year to recapitalize and modernize its Total Force combat squadrons.

2. Grow the number of Reserve Component fighter squadrons and increase the number of fighters assigned to each. Capturing and retaining experienced fighter pilots who exit the Active Component is the most efficient and least disruptive way to increase the number of experienced combat pilots in the Total Force.

Grow the number of Reserve Component fighter squadrons. Many Reserve Component wings have a single fighter squadron. The U.S. Air Force could cost-effectively grow the number of fighter squadrons in its Reserve Component by taking advantage of unused ramp space and infrastructure at bases that host Active Component wings. Collocating new squadrons in wings with seasoned squadrons that are equipped with similar type aircraft would also help facilitate training the new unit’s pilots and other personnel.

Grow the number of primary assigned aircraft at Reserve Component fighter squadrons. Most Reserve Component wings with a fighter mission have a single squadron of 18 primary aircraft. Increasing the number of primary assigned aircraft in these units to match the number of aircraft in Active Component squadrons would gracefully grow the Total Force’s combat capacity and pilot corps with fewer adverse effects.

Leverage Reserve Component pilot experience to absorb Active Component pilots. As the U.S. Air Force grows its Reserve Component, it should use some of that additional capacity to help absorb new AC pilots graduating from their initial fighter qualification courses. The Air Force has previously used the Reserve Component in this way, but its effectiveness faltered as the RC’s aircraft aged.

3. Recapitalize and modernize combat forces to improve mission-capable rates. If boosting production of the F-35A alone cannot alone arrest inventory declines and improve mission-capable rates, acquiring advanced F-16 models to replace legacy airframes and grow the inventory should be considered. While neither the F-15EX nor new-build F-16s offer the full combat utility and survivability of 5th-generation fighters, they do offer other benefits, such as easing unit transitions and mitigating the downtime that comes with converting 4th-gen squadrons to fly the 5th-gen F-35A.

Procure the F-15EX and advanced versions of the F-16 to triage legacy aircraft availability and prevent squadron closures. Replacing current F-15Cs and F-15Es with the F-15EX and replacing F-16s with an advanced version of the F-16 would modernize the Air Force’s fighter squadrons with minimal operational downtime. These aircraft are mature and will achieve high mission-capable rates, while experienced F-15 and F-16 pilots can convert easily to fly the new jets, retaining their experience in the Total Force.

Fully fund weapon system sustainment accounts, fully man all maintenance billets, and increase aircraft maintenance depot throughput. The Air Force must fully fund and resource the weapon system sustainment accounts—to include aircraft spare parts, and maintenance personnel—of all its aircraft if it is to achieve the mission-capable rates necessary to absorb and maintain the readiness of its Total Force. Of course, the optimal way to decrease the staggering weapons system sustainment costs of maintaining aging aircraft is to replace them as rapidly as possible.

4. Recapitalize and modernize the Active and Reserve Components concurrently. To fully integrate the Reserve Component into all its operations, the Air Force should avoid segregating the Active and Reserve Components. Ensuring concurrency supports the interdependencies and efficiencies between the two components that increase their flexibility in peacetime and wartime.

Ultimately, the U.S. Air Force must build and maintain an experienced combat pilot corps that has the strategic depth to meet the nation’s global security needs. The Air Force today is too small to do this now, which is the true root cause of its persistent pilot shortfall crisis. Growing the size of the Air Force and modernizing its forces—especially its Reserve Component’s combat squadrons—is the only viable, cost-effective means to resolve this shortfall and increase the retention of experienced combat pilots across the Total Force.