Flashback to 1986: America, at the peak of the Reagan military buildup, three years before the fall of the Berlin Wall, five years shy of the dissolution of the Soviet Union, 13 years after the end of combat operations in Vietnam.

The U.S. defense budget was $295.5 billion that year, and the following year it would exceed $300 billion for the first time ever. Defense accounted for 6.6 percent of U.S. gross domestic product in 1986, a level it has not even approached since. True, defense spending has nearly tripled since then—the 2023 budget was $857 billion—but the share of the overall economy invested in national defense is only half as much now as it was in the mid-1980s.

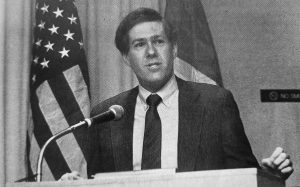

This is helpful context as we consider the far-reaching overhaul—or “re-optimization,” as Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall III calls it—of the Air Force and Space Force and the Secretariat that oversees the two.

Kendall assumed his first Senior Executive Service job in the Pentagon in 1986, as Assistant Deputy Undersecretary for Strategic Defense Systems. Over the next eight years, in that role for two, and then as Deputy Director of Defense Research and Engineering for Tactical Warfare Programs, he served under three U.S. Presidents and six Secretaries of Defense during a time of momentous change: the end of the Cold War, the decisive victory in Operation Desert Storm, marking perhaps the pinnacle of American military might, and then the beginning of the post-Cold War drawdown, which set the stage for where we find the Air and Space Forces today.

Secretary of the Air Force – Frank Kendall IIIWe’re in a race. And we can’t just hope we win.

In what may be his last year in public service—Kendall, who turned 75 in January, is already the oldest Secretary of the Air Force in history, and he has not committed to extending his tenure past President Joe Biden’s current term—the Secretary is hardly taking a victory lap. Having focused the services’ modernization efforts around seven Operational Imperatives designed to accelerate the injection of new capabilities into the force, Kendall is now setting his sights on organizational impediments to change and on what might be called organizational hubris.

The impediments are structural, he argues. They include institutional stovepipes, insufficient centralization and oversight over critical skill sets and areas of technology development, and also inadequate depth of talent and equipment to absorb combat losses and remain effective and capable.

“We moved away from a focus on staying ahead of an aggressive competitor to being efficient,” Kendall says, “… but not postured or oriented on being currently ahead of and staying ahead of a peer competitor.”

In the years after Desert Storm, the Air Force devolved from deploying squadrons and wings that had trained and operated together to deploying individuals and assembling units as if they were pick-up basketball teams on the theory that as long as everyone knows his or her job, they can meld as a team in an instant.

This worked well enough to sustain air support over Afghanistan and Iraq and to defeat the likes of ISIS, which had no airpower or anti-air capability to speak of. It will not work to defeat the likes of China, with its sophisticated air defenses, long-range air-to-air and air-to-surface missiles, anti-satellite weapons, and the home-field advantage in almost every Pacific conflict scenario.

The Space Force, meanwhile, is a an accelerating work in progress, converting bespoke capabilities—communications, precision navigation and timing, and various sensors—built for a benign environment to support various military and civilian requirements, into an integrated military capability that can operate through attacks, defend itself when threatened, and inflict harm if necessary.

Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman uses the analogy of converting the Merchant Marine into the U.S. Navy for World War II. It wasn’t built for or trained for that new mission, so adapting to meet those new mission requirements demands different training, tactics, and equipment because it must now operate and survive in a contested domain.

Saltzman was 17 and thinking about where to go to college in 1986 when Kendall got his first SES job at the Pentagon. Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David W. Allvin was starting undergraduate pilot training, Acting Undersecretary of the Air Force Krystin E. Jones was a freshman in high school. They represent Kendall’s inner circle, the architects and masters of the four-month sprint to a set of changes they will unveil at the AFA Warfare Symposium Feb. 12.

Take note of their relative ages. These are highly accomplished and experienced people, but they are newbies in comparison to Kendall, whose unusually long and varied experience enables him to be mentor and professor, the wise man at the head of the table, imbued with the first-person experience and perspective to ask hard questions, challenge all assumptions, and effect real change inside the impossible bureaucracy of the Department of Defense.

Of course, years of experience do not equate to wisdom or brilliance. As a wise boss once made clear to me many years ago, don’t be fooled by a number. “There’s a difference between 20 years of experience and one year of experience 20 times,” he said. Not everyone learns from what they’ve endured.

Kendall’s experience is clearly cumulative. When he talks about China as an adversary, it’s clear he’s seen this movie before, understands the plotlines, anticipates the different ways it might play out.

“China is a thinking, well-resourced adversary. They’re now thinking about the things we’ve said we’re going to do and how they’re going to defeat them. That’s why we have to re-optimize. We’re in a race. And we can’t just hope we win. We have to actually do things to make sure we stay ahead.”

What Kendall has done, says Saltzman, is to force a level of introspection that borders on the uncomfortable. That introspection has yielded a keener sense of urgency.

“We’re out of time,” Saltzman says. “We really have to double down on the tempo of what we’re trying to do. And that puts things in a different perspective. That changes our resourcing strategies. That changes the expectations.”

And what are America’s expectations? Our nation has options. We can remain a superpower and the singular stabilizing force around the globe, enforcer of order, promoter of open and competitive markets, of freedom and individual liberty. Or we can fade from the world stage. Staying the course is not an option. We can invest our way back into a commanding lead in the midst of great competition or, as Allvin recently told this publication, we can become “a regional power in 2050.”

One should not need 50 years of experience to answer that correctly.