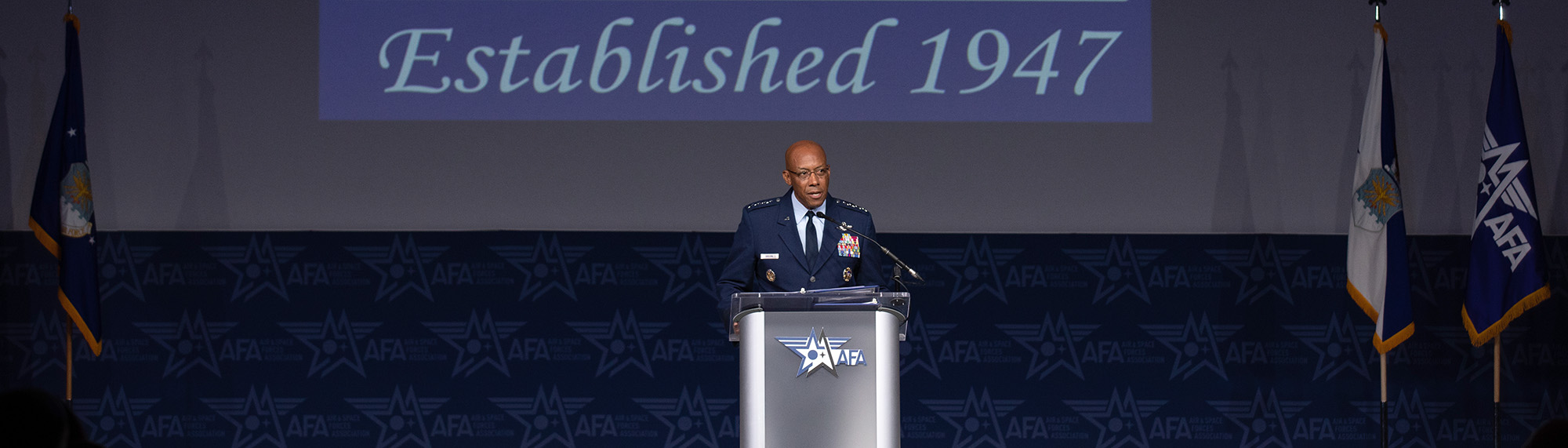

Air Force Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr.’s keynote address at the Air & Space Forces Association’s biggest-ever Air, Space & Cyber Conference last month looked to the past—and to the future.

“As I looked across the security horizon, three things crystallized for me,” Brown said. “Uncontested Air Force dominance is not assured. Good enough today will fail tomorrow. And we must collaborate within and throughout to succeed.”

Brown led his audience on a sweep through 75 years of history. The Wright Brothers, bicycle makers with a dream, proved human flight was within their grasp. He cited Billy Mitchell, Hap Arnold, Jimmy Doolittle, Amelia Earhart, and Benjamin O. Davis Jr. as visionaries who risked their lives and careers to unlock possibilities and redefine warfare, commerce, and our very human existence ever after.

“We proved that we could rise above any challenge,” Brown said. “We proved that we were willing to take risk. And we proved that we could solve any problem.”

America has also proven fickle. Our nation had repeatedly neglected its military, and in particular its air forces, in peacetime, only to have to reinvent them when conflict arose. The U.S. was not ready for war in 1941, despite warning signals that, in the light of history, seem obvious. Germany had been at war in Europe for more than two years by then. Japan was increasingly belligerent and isolated.

To deter war, we must demonstrate both superior capability and sufficient capacity to endure a fight.

Today, as then, we can see a thuggish foe in Europe, where Russia’s war on Ukraine, though not going according to Vladimir Putin’s plan, could still expand to other formats. In Asia, China has replaced Japan as a dominant regional power eager to assert its dominance and influence on its neighbors.

Building the capabilities to face down China or Russia and others who might threaten the U.S. or its allies is our new and familiar challenge. “We have done this before,” Brown said. “And we will do it again.”

The Air Force’s equipment is still as good or better than any on Earth—but there is not enough of it to meet defense strategy demands.Airmen’s tactical skills are good, but could be better—practice makes perfect, but most Airmen aren’t getting the flight time they need to maximize proficiency. America’s edge—unparalleled for a generation—is no longer what it was. Without that strategic overmatch, which made it possible to face off larger enemies with smaller, more capable forces, our less-is-more formula no longer works. Instead, less is really less. America cannot fight a war of attrition with the likes of China, a nation five times more populous than ours.

Yet America has advantages. First and foremost, we have friends. Our forces, as Brown says, are “integrated by design.” The United States does not intend to fight alone, but as an integrated team with allies and partners. Russia’s attack on Ukraine sought to splinter the NATO alliance, but instead reinvigorated it, drawing in new members and renewing every member’s commitment to the collective. There is no such organization in the Indo-Pacific, but our allies and partners are many. We share a common commitment to democracy, free speech, human rights, the rule of law, and weapons like the F-35 Lightning II fighter jet, which we operate in common.

Such integration leverages our great national capacity for collaboration, innovation, and invention.

Within the Air Force itself, Brown seeks a cultural shift, away from centralization toward distributed decision making that empowers individual Airmen to make decisions on their own. Leaders must convey clear and unambiguous intent, Brown said, and “then get out of their way.” Trust must extend down the chain. Expeditionary forces cannot be effective if they must be directed at every moment. There is no clearer lesson from Russia’s failures in Ukraine than this.

This is also at the root of Agile Combat Employment (ACE), the Air Force’s flexible operational concept. ACE will complicate the fight for the enemy, but it requires Airmen to be more flexible and capable themselves. It means less specialization and more jacks-of-all-trades. It will be more demanding of everyone.

The Air Force’s new force generation model is also part of this culture change. Here, the issue is as much external as internal. Better planning is better for Airmen. But better communication to the rest of the Defense Department leadership and to the combatant commands is crucial. The Air Force is not a perpetual fountain of capability.

Forces have a life cycle, must be built up and prepared before they become ready, and that readiness cannot be perpetually sustained for every unit. Capabilities can be worn out, broken, and lost. USAF’s B-1 bombers flew so hard, so often, and for so long over the course of 20 years of war in the Middle East that many are beyond repair. That capability and capacity, now lost, must be replaced.

Flexible thinking is paramount in this new construct. Not only must Airmen be ready and able to do whatever is asked—even if it’s not one’s trained specialty—but aircraft must be flexible, as well. Experiments with palletized weapons from C-130s or C-17s, developing new electronic warfare and directed-energy capabilities, and adding those to unconventional platforms makes our Air Force less predictable. That makes defense harder for our potential adversaries.

Brown also outlined plans to change the organizational construct of Air Force units down to the wing level, making them more consistent with the way the other forces are organized, thus making it easier for Airmen to “plug in” to joint commands.

Our nation must also do its part. Congress must get out of its own way. We are once again ending a fiscal year without a budget, a wasteful habit that costs taxpayers billions and undermines our investments in national defense.

In the coming years, America must also restore balance to our nation’s defense and ensure we are investing at least as much in our Air and Space Forces as we are in our Army and Navy. That has not been the case for 30 years in a row. Meanwhile, 20 percent of Air Force spending is siphoned off as a “pass-through” to fund other DOD agencies.

Investing in our Air and Space Forces will ensure Airmen and Guardians not only have the advanced capability to defeat rivals, but also the capacity to present an overwhelming threat. It’s not enough to have the greatest airplanes in the world, one has to have enough of them to fight. To deter war, we must demonstrate both superior capability and sufficient capacity to endure a fight.

Finally, we must invest in readiness. Capability is the combination of technology and skill. Having the world’s greatest combat jets is only helpful if our pilots are sufficiently skilled to employ them effectively. That takes practice. Pilots today are getting less than half the flying hours they need. Training must be regular and consistent to be effective.

The credible capacity to fight is the No. 1 deterrent to war. What rival begins an action without first considering the odds? Our job as citizens is to ensure those odds are always in our nation’s favor.

America has been here and done that before. And, yes, we can do it again—so long as the Air Force is resourced to do so.