China’s rise, the birth of the Space Force, and even the COVID-19 pandemic are all forcing functions that can help shake up today’s mature bureaucracy and awake it from its lethargy.

Russian aircraft probe U.S. defenses in Alaska and Europe, and its cyber instigators prowl the Internet, fueling hate and discontent on social media, driving wedges into the cracks in our oft-divided nation. Confidence in our institutions continues to wane. Further south, China flexes its muscles, emboldened by what it wishes to believe: that America is atrophying, fading from preeminence, and that America’s decline clears the way for China’s ascent. After sending combat jets into Taiwanese airspace last month, China circulated an ominous Internet video depicting Chinese bombers destroying a U.S. base in Guam.

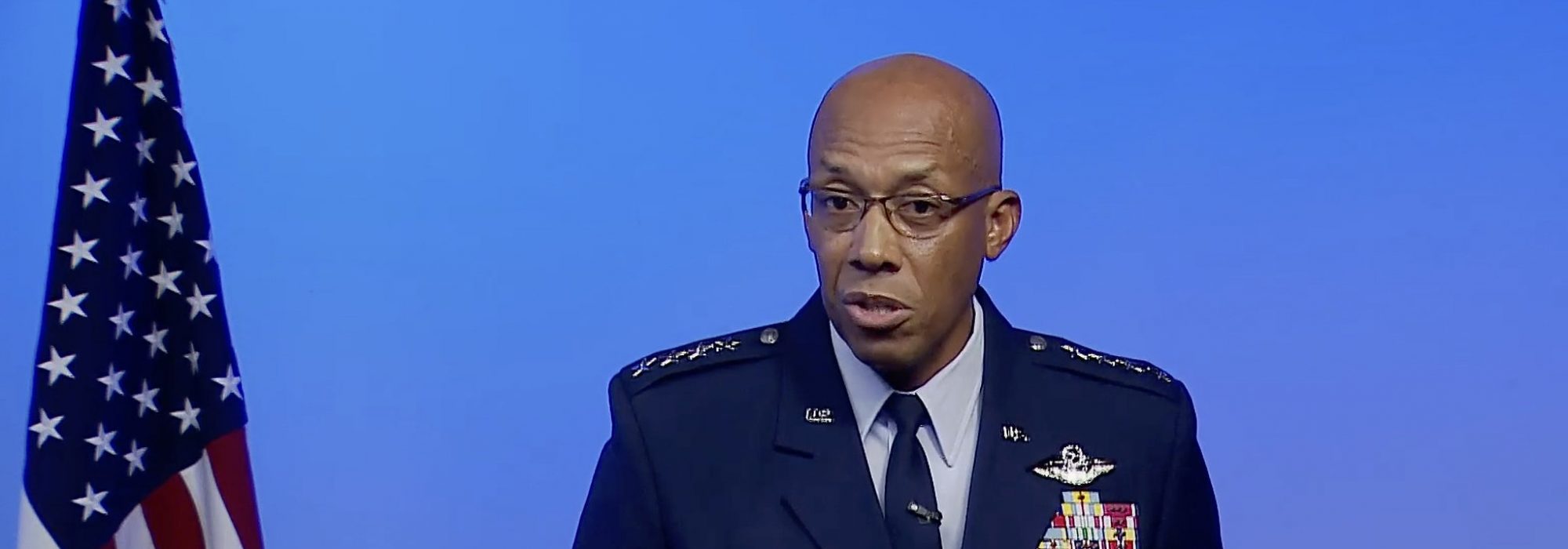

No wonder Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. keeps saying, “Accelerate change—or lose.”

“We’re at an inflection point, and we can’t defer change,” Brown said in his first major address as Chief, a statement of intent at the Air Force Association’s virtual Air, Space & Cyber Conference last month. “We have a window of opportunity, a window of opportunity to change, to control and exploit the air domain to the standard our nation expects and requires of its Air Force. If we don’t change, if we fail to adapt, we risk losing.”

Brown’s predecessors prepared the way, he said, but now the pace of change must quicken. War may not be imminent, but the rising risk must be seen for what it is: a call to action. As a past commander of Pacific Air Forces, he knows the U.S. can’t compete with China numerically. Capability, ingenuity, speed, and talent are our differentiators.

Leadership without risk is called management. We don’t need more managers in the Air Force.CSAF Gen. Charles. Q. Brown Jr.

China’s rise, the birth of the Space Force, and even the COVID-19 pandemic are all forcing functions that can help shake up today’s mature bureaucracy and awake it from its lethargy.

“We have two options,” Brown said. “We can ‘admire’ the problem and talk about how tough it’s going to be, how hard the decision will be to make, or we can take action. I vote for the latter.”

Airmen take note: This is the example he wants you to follow. The American way of war has long leveraged the independent creativity of individual commanders. Ours is a matrixed military in which commanders are supposed to have leeway to apply judgment. In recent years, however, that philosophy has atrophied. Trust in subordinates waned. If your boss doesn’t trust you, you won’t trust those beneath you, and they won’t trust their subordinates. The result is paralysis.

American forces are better trained, better educated, and generally better equipped than their peers. They must likewise be better trusted. Subordinates must be confident in their ability to make decisions and take action—and yes, to make mistakes. We learn more from our failures than our successes, but only if we survive to face a similar decision in the future. If every failure kills a career, no one learns a thing.

This goes back to the very root of the Air Force and the leaders who put their careers and their lives on the line as they invented air power. Pioneers such as Billy Mitchell and Jimmy Doolittle embraced risk in ways we can barely imagine today, betting it all on their instincts.

Now in its eighth decade, the Air Force’s risk aversion is as great a threat as China and Russia. “Folks don’t want to change once they’re in their comfort zone,” Brown told me in an interview following his talk. “You’ve got to have a forcing function that drives change.”

The so-called frozen middle—those mid-career Airmen and civilians whose embrace of rules and regulations shrouds that underlying discomfort with change—slow-rolls innovation and dampens the enthusiasm of their subordinates. Worse, they drive away the innovators.

“‘Leadership without risk is called management,’” Brown said, quoting retired Lt. Col. Rich Cole, whose father was Jimmy Doolittle’s copilot for the famous Doolittle Raid. “We don’t need more managers in the Air Force. We need more leaders. I plan to lead change. And by leading change, we’re going to have to take some risks.”

Airmen can’t be afraid to speak up in meetings, holding their comments for the “meeting after the meeting.” That’s a leadership problem. “We must have ‘the meeting after the meeting’ in the meeting,” Brown said. Get the ideas on the table. Invoking former Defense Secretary and Marine Corps Gen. James Mattis, Brown’s boss years ago in U.S. Central Command, he advocated Mattis’ concept of command and feedback as opposed to command and control. “It’s the dialog that happens between different levels of command,” he said.

Commanders in the field need not wait for direction from above. “In some cases,” Brown said, “you need to figure out what to do on your own.”

So, do what Brown does: Tell your boss what you intend to do. Wait for a response. If the boss doesn’t say otherwise within a couple of days, act. Afraid that’s no way to get promoted? It’s how Brown made Chief of Staff.

“That’s the same kind of approach I think our Airmen need to take,” Brown said. “They need to be thinking about what they’re doing, communicating what their intent is, and then wait a little bit of time, give their supervision a chance to respond. And if they don’t respond, they need to move.”

Brown himself is moving out on plans for a new deployment model and on finding ways to pay for essential modernization. Weapons and systems that won’t make the Air Force better and more effective in a high-end fight against a Chinese force that will dwarf the U.S. numerically shouldn’t be part of that equation. They’ll need to go. Excess bureaucracy that doesn’t add to the force’s lethality should go, as well. There are lessons in what Gen. John W. “Jay” Raymond is doing with his leaner Space Force, Brown says. Maybe the Air Force can borrow from that model.

Will Roper, the department’s chief acquisition executive, is likewise aligned. He’s aiming to accelerate acquisition and to deliver supreme connectivity to the Joint Force—to create a secure “Internet of Military Things” that extends to the edge of the combat cloud.

Roper’s vision for the Advanced Battle Management System is a network that connects the Joint Force in real time, worldwide. It’s not easy. F-35s struggle to communicate with F-22s. But it’s a workable problem. He’s also accelerating the development and engineering of new systems and platforms through the service’s embrace of digital engineering. Like Brown, accelerating change.

ABMS is to military systems what better communication is to Airmen in any fight: a key to faster, better informed decision-making. It is the digital analog to the human collaboration Brown seeks to unlock by empowering Airmen to speak up and think for themselves.

Not every new idea will be met warmly. Not all will be successful or even worth pursuing. But that isn’t a failure. Trying and failing is better than not trying at all.