The Trump administration arrived in Washington promising to restore America’s military, reinvigorate deterrence, and bring back its warrior ethos. These are not things that can change overnight, but there is evidence of progress.

Topics that were gingerly avoided six months ago like the Next-Generation Air Dominance fighter or offensive space weapons, are now emerging into the open. Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David Allvin is ramping up his campaign for “more Air Force” in bolder and more colorful terms. At any moment, he said at the AFA Warfare Symposium in March, the Air Force must be able “to put a warhead on a forehead anywhere the President might want.”

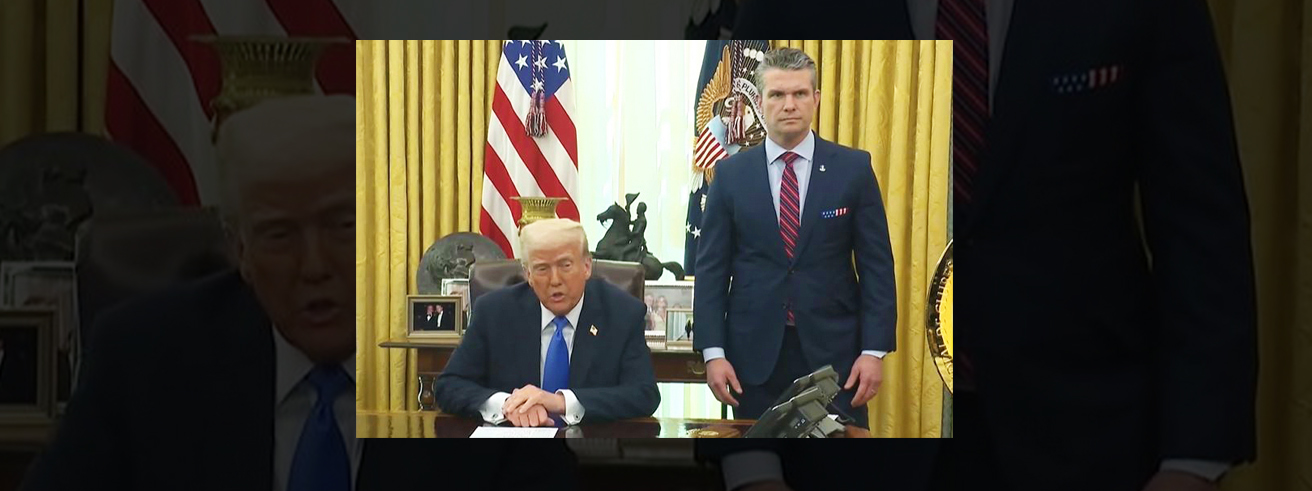

That kind of talk resonates with many, including President Donald Trump, who held a White House news conference in March to announce America’s first new fighter plane in 24 years.

The last time a new Air Force fighter was announced—the F-35, in 2001—those honors were delegated to the Secretary of the Air Force. This time it was an Oval Office event featuring the President, Secretary of Defense, and Air Force Chief of Staff, who stood beside a rendering of Boeing’s F-47, which aims to be the fastest, stealthiest, most reliable modern fighter on Earth.

Revolutionary thinking and a newfound military swagger.

Just weeks earlier, Allvin gave fighter designations—for the first time ever—to a pair of low-observable drones. The General Atomics YFQ-42 and Anduril YFQ-44 are autonomous Collaborative Combat Aircraft that will operate as armed wingman, extensions of the combat power of the F-35 and F-47. The fighter designation might be a stretch, but it represents revolutionary thinking and military ambition, even swagger.

Space superiority, meanwhile, is having its own moment. Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman turned up the volume on Guardians as warfighters and space as a warfighting domain from the moment he became Chief in 2023. Yet he has carefully stewarded his messaging, navigating both restrictive classification rules and the do-no-harm sensibilities that space operators have long held as sacrosanct.

It’s not that the United States could not shoot down a satellite—the Air Force demonstrated the feat with a missile fired from an F-15 in 1985, and in 2008’s Operation Burnt Frost, a Navy Aegis missile cruiser shot down a failed satellite from the Pacific Ocean. But being able to do such things did not mean we would.

At the AFA Warfare Symposium in March, however, Saltzman declared “space control” the newest “core function of the Space Force” and his “number one priority.” Said Saltzman: “Domain control is the special province of warfighters, a unique responsibility that only military services hold.” It comprises the mission areas required to contest and control the domain, including kinetic means, to disrupt, degrade, and even destroy enemy satellites.

“Historically, we’ve avoided talking too much about space control,” Saltzman said. “But why would you have a military space service if not to execute space control?”

China and Russia have demonstrated anti-satellite missiles, orbiting grappling arms, and threatening maneuvers in space for years, and the U.S. hurled back words: “irresponsible” and “dangerous.” Counterspace operations evoked shadowboxing and cat-and-mouse maneuver, not explosive force. Saltzman has opened that aperture and is selling the concept to his own Guardians, as well as the public.

Troy Meink, President Trump’s nominee for Air Force Secretary, channeled the CSO at his late-March confirmation hearing. Meink spent the bulk of his professional career in space intelligence, most recently as principal deputy director of the National Reconnaissance Organization. That makes him something of an enigma; a political appointee whose public profile is essentially blank.

“Space control and counterspace systems are critical,” Meink told the committee, explaining the Space Force’s most critical needs. “That is probably the area we are being most stressed in from a threat perspective.” In written testimony, he said, “The Space Force must prioritize space domain awareness, resilience, and capabilities that ‘hold at risk’ adversary space assets to protect the Joint Force.”

At the Warfare Symposium, Air Combat Command’s Gen. Kenneth Wilsbach made clear space is not just for space people. “We should start talking about air superiority together with space superiority as a combo,” he said. “You’re likely not going to be able to achieve air superiority in the modern sense without space superiority as well.”

Saltzman, in a visit to AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, mused that the line between air and space—what some have called “near space”—could also be called “far air.” He expressed pride at the ability of the two services to cover the seams between the domains together.

Everything now depends on space for navigation, communications, targeting, and more, Wilsbach said. “If you don’t have air and space superiority, you’ll … have a very difficult time achieving any of those other objectives.”

Some Air Force leaders have posited that air superiority must be achieved in new ways in the modern age, given increasingly lethal enemy defenses. Air forces have always faced this challenge. The U.S. Army Air Forces could not achieve air superiority in the early days of World War II, and American forces paid a devastating price. By the end of the war, however, USAAF had surpassed air superiority and attained air supremacy, as it did in Operation Desert Storm nearly 50 years later. In that war, the U.S. Air Force was so dominant the Iraqi air force fled the battlespace, incapacitated.

“There’s been some talk in the public that the age of air superiority is over,” Wilsbach said. “I categorically reject that.”

The Air Force has always been subject to competing intellectual visions, those who believe wars can be won in the air and those who view airpower as a supporting element to surface operations. While these need not be mutually exclusive, the question is often oversimplified. The Army’s 1980s-era Air-Land Battle doctrine subordinated airpower; Desert Storm reversed that concept, demonstrating that airpower as the primary force could be a more decisive means of military engagement; and Operation Allied Force to end Serbia’s unjust war on Kosovo was a rare demonstration that airpower alone can be decisive.

American leaders over the past quarter-century misread or ignored those lessons and bungled extended military entanglements in Afghanistan and Iraq. In Syria, where airpower all along was the primary element of force application, it was only late in the fight that intense airpower was applied for strategic, not just tactical effects.

Yet, despite our nation’s reliance on air- and spacepower, we put off modernizing those forces. Like a homeowner juggling bills and hoping to get one more winter out of his furnace, we paid the short-term bill for counterinsurgencies and ignored the investment necessary to update our combat air forces. Now those bills are now due.

The new administration is saying the right things. But words alone will not buy air and space superiority. That will take money. And the only real measure of a government’s commitment to something is the amount of resources it’s willing to commit. Stand by for the incoming 2026 budget request.