The United States needs a layered approach to defeat even the idea of an attack from the far north.

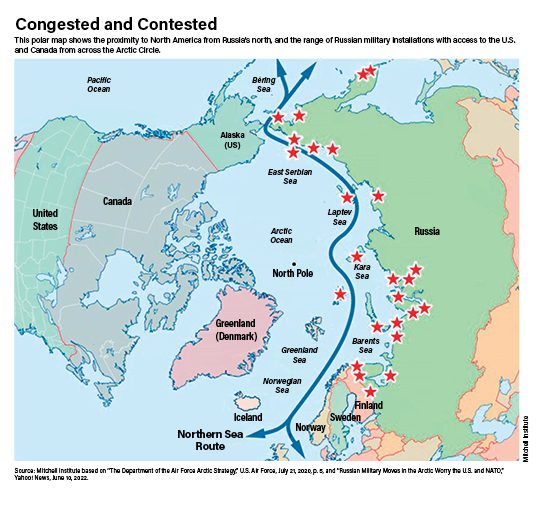

Since the dawn of the Cold War, the high north has been seen as an attractive attack vector for long range strike for one simple reason: it provides shortest distance between the United States and Eurasia. Today, the Arctic it is still seen by U.S. adversaries like Russia and China as an appealing attack vector for their missiles and long-range aviation assets given both the Arctic’s geography and insufficient monitoring by the United States. The growing Arctic presence of China—a self-proclaimed “near-Arctic state” and custodian of an increasingly robust long-range aviation and missile inventory—reinforces the region’s significance as a staging ground for conventional air and cruise missile attacks.

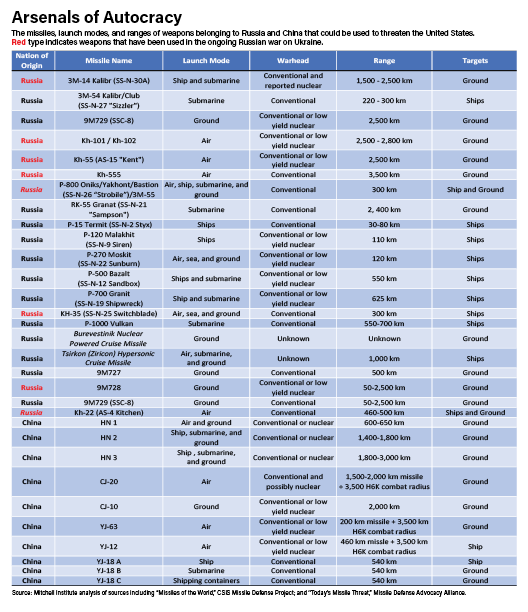

Yet the U.S. ability to detect, track, attribute, and counter attacks coming from the north has significantly diminished since the end of the Cold War, even as America’s potential adversaries have prioritized development of missiles of all types over the same three decades. China and Russia have explored options to employ long-range, conventional weapons to deter U.S. leaders without provoking a nuclear response. Chinese doctrine describes precision strikes as a means of “war control” to manage escalation and frame power-projection nodes. Missile warfare is becoming a premier means for Russia to project power; in Ukraine, Russia has launched hundreds of ballistic and cruise missiles, as well as suicide drones, targeting power grids and other critical infrastructure in an attempt to force Kyiv into a settlement.

Caitlin Lee directs the Acquisition and Technology Policy Program at RAND. Aidan Poling is a research analyst with the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.

Download the entire report at

As the 2022 Missile Defense Review noted, missile threats to the U.S. homeland have “rapidly expanded in quantity, diversity, and sophistication.” Modern conventional cruise missiles pose the greatest threat; they are harder to detect, track, target, and intercept than ballistic missiles.

Adversaries have begun to favor cruise missile development over ballistic missiles because they greatly complicate detection and early warning. This is part of a broader missile development trend that favors increasingly maneuverable designs. Hypersonic cruise missiles, for instance, fly at Mach 5 or faster. While hypersonic missiles produce a greater heat signature and are less maneuverable, their extreme speed produces a considerable advantage. China’s fractional orbital bombardment system, or (FOBS), takes this capability to a still more striking level, with a highly maneuverable hypersonic glide missile that is launched into orbit and then re-enters the earth’s atmosphere on an unpredictable trajectory.

To date, the U.S. has only mounted a tepid response to these threats. Throughout the post-Cold War period of the 1990s and early 2000s, Arctic defense planning took a backseat to other geopolitical concerns for both the United States and Russia. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Russian economy imploded, and its Northern Fleet and air assets fell into disrepair. Post-Cold War arms reduction treaties, combined with a major shift in the U.S. military’s focus toward operations in the Middle East after Sept. 11, 2001, contributed to DOD reducing its Arctic focus. DOD closed or downsized almost all of its bases in Alaska and significantly shrank other capabilities for defending the northern approach to the United States. This is reflected by NORAD’s continued reliance on the aging North Warning System (NWS), a network of 47 long-range and short-range radars first fielded in the 1980s and equipped with 1970s-era technology.

This system was only designed to identify approaching Soviet bombers after launch and flying within radar range. Today, it cannot provide early indications and warning of adversary force posture changes in the Arctic, which could be a prelude to an attack. Nor can the NWS detect air and missile threats launched from inside Russia or bombers, cruise missiles, drones flying too low or too far to be detected by its radar.

As Russia and China develop stealthier cruise missiles and diversify their cruise missile launch options to include land-based, surface, and subsurface platforms, the gaps in the North Warning System’s effective radar coverage will continue to increase.

“Imagine a solid fence shrinking to a picket fence,” notes Gen. Glen D. VanHerck, head of the North American Aerospace Defense Command and U.S. Northern Command. “And now you have cruise missiles that can get through your capability to detect.”

The legacy U.S. air and missile defense paradigm, focused as it is on kinetic intercept, remains important and needs to be urgently modernized, but an overreliance on kinetic kill platforms, delivery systems, and weapons alone limits warfighter options.

A network of ground-based radars—including those in the North Warning System—and a small number of fighters on air defense alert at air bases around the country provide today’s air defense of the contiguous United States. These fighters are on alert status to rapidly respond to and intercept foreign military aircraft, such as Russian bomber patrols that routinely fly near and occasionally into U.S. airspace. Air Force fighters also intercept unidentified aircraft, aircraft that have strayed from planned flight paths, and aircraft that are not properly communicating with air traffic control.

The small numbers of fighters and the lack of a system of sensors that can detect low-flying targets over long ranges limit the system’s effectiveness against modern cruise missiles and other threats. Air defense systems such as Patriot, Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD), or the National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile System (NASAMS), which is used to defend the Washington, D.C., National Capital Region, offer some defense against low-volume missile threats, but these low-density, high-demand assets are extremely costly; they cost more per shot than the missiles they defend against, and are ineffective against many types of cruise missile and drone threats.

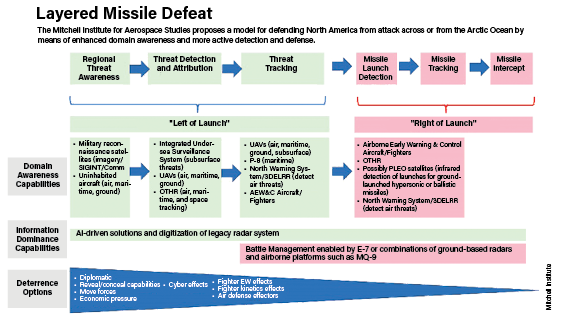

U.S. defense leaders have gradually adopted a new emphasis over the last decade on a holistic concept called “missile defeat.” and then than narrowly focusing on kinetic kill options to deny adversary attacks, missile defeat involves using the entire spectrum of options to prevent and defeat missile threats, from countering proliferation to early indications and warning and, of course, detection, tracking, and intercepting cruise missiles. It also seeks to integrate defensive, offensive, passive, kinetic, and non-kinetic capabilities, such as cyber warfare, directed energy, and electronic attack.

NORAD/NORTHCOM embraces this new emphasis on domain awareness and information dominance. Early detection of a potential threat can open up decision space for U.S. leaders, enabling moves left-of-launch or even left-of-conflict to reduce the risk of an attack in the first place. As VanHerck notes, “If I’m shooting down cruise missiles and ballistic missiles, we’ve failed in deterrence, and that’s not where we want to be.” Domain awareness and information dominance likewise remain prerequisites for any actions to defeat missiles right-of-launch—after kinetic or non-kinetic attacks have occurred.

However, the new emphasis on domain awareness and information dominance is not without challenges. VanHerck testified to Congress that the missile defeat approach, which favors detection over tracking and countering, is at risk because of a sheer lack of capabilities in the Arctic. The January 2023 intrusion of a Chinese spy balloon into U.S. airspace by way of northwest Canada caught the nation off-guard and highlighted this severe lack of domain awareness in the Arctic. VanHerck told lawmakers: “We are not organized, trained or equipped to respond in the Arctic.”

Another Arctic expert, Ketil Olsen, formerly Norway’s military representative in NATO and the European Union, who now heads Andoeya Space, a Norwegian state-controlled company that tests new military and surveillance technologies, called the region “a dark area on the map.” The lack of domain awareness prevents the United States from obtaining the early warning and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) information necessary to anticipate and take actions to deter air and cruise missile attacks.

A Layered Approach to Missile Defeat

Recognizing the gaps in U.S. northern tier defenses, VanHerck has continued to push for a modern, layered air and cruise missile defense, which involves working with other U.S. combatant commands as well as allies and partners. He has said NORAD/NORTHCOM’s missile defeat architecture, known as Homeland Defense Design 2035, will be “vastly different from the way we do it today with fighters, tankers, AWACS, and those kinds of things.”

DOD is already investing in certain components of air and missile defense that will improve NORAD’s ability to detect, track, attribute, and counter hostile air threats in the Arctic and across its full area of responsibility, but funding for the effort is not coordinated under one portfolio or a strategy for air and cruise missile defense of the homeland. DOD can achieve a more secure future by accelerating these efforts and developing a common vision shared by all the stakeholders in the Arctic.

Analyzing the risks and opportunities in the Arctic, the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies has developed a framework for a layered missile defeat approach in the Arctic, with particular emphasis on left-of-launch detection and tracking.

The first layer is regional threat awareness, consisting of networked sensors operating in multiple domains to provide early indications and warning of potential threats. Adversaries may show signs of intent by making force posture changes and logistical preparations in the days, weeks, and even months prior to an attack. Today for instance, Russia is building up its military bases in range of Alaska. By tracking activities that could be a prelude to hostilities, U.S. leaders could be better equipped to manage the threat, providing more time and options for the United States to deter or prevent an attack.

ISR satellite assets that can be used to map out activity and detect changes in adversary behavior are one obvious and attractive solution to improve indications and warning in the Arctic. Already, commercial companies and U.S. partners and allies operating satellites with Arctic coverage could help fill current DOD satellite gaps.

DOD and Congress: Next Steps

To create the capabilities needed for this multi-layered defense, Congress and DOD must work together to:

Establish a Joint Capability Technology Demonstration Focused on Cruise Missile Defense of the Homeland. DOD and Congress should launch a joint capability technology demonstration (JCTD). After acquisition responsibility for cruise missile defense of the homeland moved from the Missile Defense Agency to the U.S. Air Force, a previous JCTD to examine a layered approach to cruise missile defense was scaled down to focus on the National Capital Region. Congress and DOD should fund a broader JCTD to experiment with air, space, surface, and subsurface capabilities that could provide an overlapping, layered cruise missile defense for the Arctic.

Create a Dedicated Fund to Bolster Deterrence in the Arctic. A new North American Deterrence Initiative focused on increasing investments for cruise missile defeat and bolstering physical military presence in the Arctic would shift awareness left-of-launch and help to reduce overall costs of missile defeat. The Congressional Budget Office assessed that a comprehensive missile defense strategy for the contiguous United States would cost from $75 billion to $465 billion for an architecture with relatively robust funding for right-of-launch defense. Emphasizing left-of-launch capabilities in the Arctic might better bolster deterrence and reduce costs. A second focus of the new fund would be physical infrastructure improvements, including pre-positioned, hardened shelters to store aircraft equipment, spares, and other logistics needs, and modernizing Pituffik Space Base, DOD’s northernmost installation (formerly known as Thule Air Base, in Greenland). Expanding the U.S. military’s physical presence in the Arctic is another key to bolstering deterrence in the region.

Deepen Ally and Partner Ties to Support Arctic Missile Defeat. The U.S. Government should strengthen and deepen bilateral and multilateral relationships with Arctic nations to bolster deterrence against air and cruise missile threats in the region. Allies have their own incentives to pursue increased capabilities in the Arctic. Denmark, for example, has already allocated $245 million to improve drone surveillance in the Arctic and is modernizing air surveillance in the Faroe Islands, while Canada is acquiring new drones for Arctic domain awareness. Norway is already working with the United States to launch communications satellite payloads.

In addition, uncrewed aircraft that are operational today—such as the MQ-9 Reaper and RQ-4 Global Hawk—can also contribute to regional threat awareness. The MQ-9 can carry a variety of sensors, including maritime surveillance radar and a signals intelligence payload. The high-altitude, long-duration RQ-4 carries a synthetic aperture radar that can persistently map an adversary’s Arctic infrastructure and activities on a persistent basis. They can also be equipped with defensive payloads, such as electronic countermeasures, to help dissuade or prevent adversaries from targeting these assets.

If indications and warnings suggest an adversary is posturing for missile strikes, NORAD/NORTHCOM needs the means to track suspected strike platforms in the threat detection and attribution phase of the framework. Examples might include a Russian bomber taking off from an Arctic base where a ship full of cruise missiles unloaded the week before, or a submarine is thought to be headed toward Canadian waters.

Routine patrols of MQ-9s equipped with maritime surveillance, signals intelligence, and electro-optical/infrared sensors could be valuable in helping to identify the number and type of potential threats. Likewise, crewed P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircraft could augment MQ-9 tracking operations.

Once a specific threat is detected, defenses must maintain tracking custody; at this threat tracking point, strikes are expected, and the goal is to provide target-quality data to kinetic and non-kinetic effectors, which could take action to deter, prevent, or respond to a missile launch.

Initial air, surface, and subsurface threat detection and attribution information could be passed to an over- the-horizon radar (OTHR), which bounces radar energy off the ionosphere to track targets over very long ranges—up to 4,000 nm. An OTHR could pass target location information on to other inhabited and uninhabited aircraft and land-based radars in the North Warning System that can reconfirm the type and number of threats.

If available, airborne early warning and control aircraft could be cued by other sensors to establish a track on airborne threat aircraft and direct fighters or other effectors to the right place at the right time to counter those threats if necessary. If available, fighter aircraft such as F-35A Lightning II jets, with their integrated sensor suites, could help track and intercept missile launch platforms before they could launch their missiles.

In the absence of available inhabited aircraft, however, it is possible that an augmented OTHR and the North Warning System could help maintain custody. Current generation UAVs possess neither the radar capabilities nor the high speeds needed to keep pace with enemy strike aircraft. But UAVs could be deployed to provide overwatch of likely launch vectors, accepting cueing data for threats from OTHR and then using on-board electro-optical and infrared sensors to verify and characterize threat aircraft. Long-duration UAVs could employ their maritime surveillance radar to locate and track potentially hostile ships and could be equipped with sonobuoys to help monitor submarine threats.

Should these left-of-launch actions fail to prevent an adversary from perpetrating a missile strike, detecting and tracking the missile right of launch becomes necessary. The Space Development Agency (SDA) has begun deploying missile-tracking satellites in low-Earth orbit (LEO), which will detect missile launches and be able to track both hypersonic and ballistic missiles powered by engines that burn hot enough to be detected.

For cruise missiles, however, inhabited aircraft, including airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) and fighters with their powerful airborne moving target radars, would be better able to track and vector countermeasures, both kinetic and electronic, to intercept incoming missiles. After this, terminal area defenses would provide the last line of defense.

Next Steps for the Air & Space Forces

The first step the Department of the Air Force must take is to exploit existing weapon systems and accelerate procurement of new ones to support a missile defeat approach. As the lead acquisition authority for cruise missile defense of the homeland, the Air Force will need to spearhead its own efforts to enhance NORAD/NORTHCOM’s emerging cruise missile defeat approach. Four of the most urgent areas the USAF should address include:

Support for the fielding of a new radar capability in the Arctic. The department is funding four new OTHR to expand coverage in the Arctic, but those systems won’t be fully operational until 2031. DOD should provide funds to allow the Air Force to invest the additional $55 million on NORAD’s unfunded priority list to accelerate OTHR fielding to 2027 and amplify the capabilities of the North Warning System with an investment of about $211 million to acquire nine NORAD-dedicated advanced mobile Three-Dimensional Expeditionary Long-Range Radars (3DELRR).

Developing a plan for a rotational UAV presence in the Arctic. With support from Canadian Forces through the NORAD/NORTHCOM chain of command, the Air Force should bolster its UAV posture in the Arctic to support domain awareness. Acting alone or in concert with other radar platforms, the MQ-9 and other UAVs can provide ISR across the layers of a missile defeat strategy. Canada may soon be joining the United States in operating the MQ-9 Reaper, which would provide additional ISR capacity and further deepen the U.S.-Canadian NORAD partnership.

Accelerating the E-7 Wedgetail. The Air Force is now confronting a major gap in its battle management capabilities as it retires the E-3 AWACS inventory and waits for the new E-7 Wedgetail to come online, with the first two arriving in 2027. The U.S. Congress should support an unfunded $633 million Air Force request to accelerate procurement of the rest of the E-7 Wedgetail inventory. This would allow the Air Force to buy parts in advance to accelerate procurement of the rest of the inventory to four per year.

Preserve legacy fighter capacity. The Air Force now plans to retire over 600 fighters over the next five years, while acquiring less than half of that number of new fighters. For the homeland defense mission, the Air Force must rely on its current and planned fighter inventory. This means the F-35, F-16, and F-15EX should not become targets for additional force cuts.

The Space Force, meanwhile, can continue to enhance and expand its collaboration with the commercial sector to boost satellite capabilities in the Arctic.

While the SDA is working to rapidly field new satellite architectures for communications and missile tracking, commercial and scientific satellites may be able to fill in immediate gaps. NORAD/NORTHCOM should build on recent prototyping efforts to test commercial satellite capability in the Arctic to develop a plan to procure commercial satellite services in the Arctic that can fill gaps until SDA constellations are fully online.

Establishing Information Dominance

Arctic domain awareness and information dominance hinge on the ability to get timely information to decision-makers—that is, both the broad understanding of the operational environment left-of-launch and the tactical information required to make an intercept right-of-launch.

To achieve that dominance, the U.S. must invest to improve several capabilities. Satellite communications are the first requirement, essential for early threat indications and warning because they provide a means to share intelligence with remotely piloted UAVs flying in the farthest regions of the Arctic, control their operations, and pipe their feeds back to decision-makers. Today, satellite communications coverage is sparse in the Arctic, but both OneWeb and SpaceX’s Starlink are expanding their network of commercial proliferated LEO communication satellites to improve coverage in the high north. The SDA’s ongoing fielding of a satellite communications transport layer in LEO will also provide high-speed data connectivity for U.S. warfighters operating in remote regions worldwide, including in the Arctic.

Connectivity between UAVs and any other aircraft to the space-based transport layer requires the benefits of optical communications technology. Laser communications leverage the highly resilient, satellite proliferated transport layer now being fielded by the SDA. The result is high-speed, flexible, and secure communication links across the air defense network that enables not only force projection abroad, but also homeland defense. Allies and partners can contribute: Norway’s Arctic Satellite Broadband Mission (ASBM) will launch two satellites into highly elliptical orbit by 2024, and these will provide improved broadband satellite communications within the Arctic region.

While environmental sensing deep into the Arctic can be facilitated by an all-weather UAV like the MQ-9B, there is a need for a multi-faceted approach to sensing weather that affects air, sea, and land operations in the Arctic. However, the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP) is well past its lifetime as a defense-dedicated weather sensor that covers the Arctic in a polar orbit, and the U.S. Space Force is developing its Electro-optical Infrared Weather Satellite Program (EWS), which will ultimately need to be disaggregated as a constellation of satellites that provide both higher performance and resilience against attack by an adversary. While the Space Force is handling the program well, Congress needs to ensure adequate resources are available to keep the program on track.

Artificial intelligence could help get the right information to the right decision-makers at the right time. NORAD and NORTHCOM have conducted global information dominance or (GIDE) experiments to fuse sensor data from a variety of platforms and dramatically reduce the time required to get threat information to decision-makers. Once one sensor picks up a potential threat, AI cross-cues that data with other sensor information to confirm, identify, and attribute the threat. VanHerck said this enables U.S. forces to go from being reactive to proactive.

Battle management platforms, including AEW&C aircraft, can add to tactical information dominance once a threat is incoming.

This overlapping, layered approach to missile defeat in the Arctic can give U.S. leaders more time to proactively shape adversary behavior and manage escalation. Early threat detection buys time to more effectively apply non-kinetic options, including diplomatic, economic, or strategic signaling actions, such as revealing U.S. capabilities or moving U.S. forces.