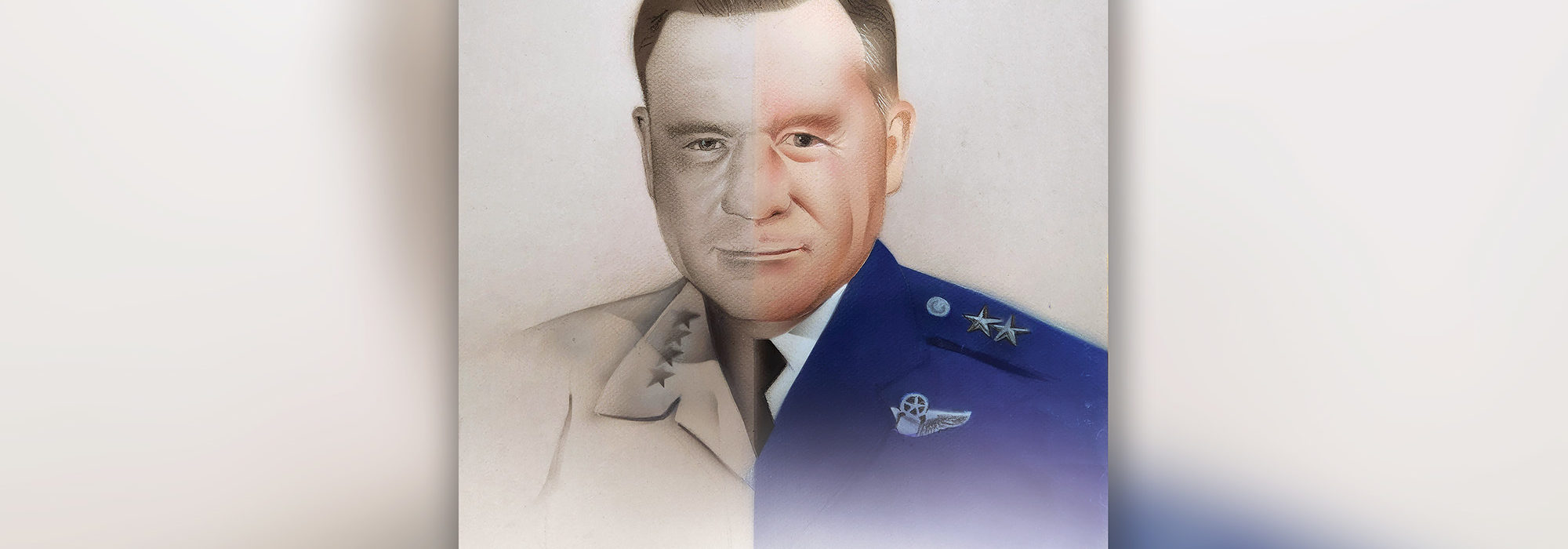

Following the President’s intent cost Gen. John Lavelle his job—

and two stars. The fight to fix his record isn’t over yet.

Seven months after taking command of 7th Air Force in Saigon, Vietnam, Gen. John D. Lavelle was suddenly recalled to Washington on March 23, 1972. Two weeks later the Pentagon announced Lavelle had retired “for personal and health reasons.”

Lavelle retired at his permanent grade of major general, without the usual confirmation at his highest grade on Active duty. Within a month, his medical malady was exposed as fiction, when Rep. Otis Pike, a New York Democrat, called for a congressional inquiry. Under pressure, then-Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. John D. Ryan released a statement, saying Lavelle was “relieved of command of the 7th Air Force by me because of irregularities in the conduct of his command responsibilities.”

Chief of Staff John RyanLavelle was relieved of command of the 7th Air Forces by me because of irregularities in the conduct of his command responsibilities.

In hearings and news articles, the story came out: The Air Force found 28 documented instances where, it said, Lavelle directed the unauthorized bombing of North Vietnam under the guise of “protective reaction” strikes, exceeding his authority and violating U.S. rules of engagement. Operational reports had been falsified to conceal the nature of the strikes. The false reporting came to light after a sergeant wrote to his senator, triggering an investigation that led to Lavelle’s dismissal. The Air Force itself was accused of a cover-up for putting out the false tale of a medical retirement.

Lavelle defended his actions, saying he had been encouraged by the Secretary of Defense and others to interpret the rules of engagement liberally. Falsified reports were submitted by subordinates who misconstrued his instructions, he maintained.

When the Air Force sought to promote Lavelle to lieutenant general, the Senate refused, but it allowed him the retired pay based on his previous four-star rank because his official relief came after his retirement took place.

Newsweek magazine called the scandal a “widespread conspiracy” in which “scores of pilots, squadron and wing commanders, intelligence and operations officers, and ordinary Airmen were caught up in the plot.” The Washington Post’s George Wilson, a leading defense reporter, wrote: “What Lavelle did—taking a war into his own hands—has obviously grave implications for the nation in this nuclear age.” Nina Totenberg asked in the National Observer, “Was Lavelle the only bad apple?”

Lavelle died in 1979 before he was able to restore his reputation, maintaining steadfastly that he had done nothing wrong. In 2007, some 25 years after his firing, previously undisclosed White House tapes demonstrated that both President Richard M. Nixon and Defense Secretary Melvin Laird had full knowledge of the actions Lavelle had directed, and that they supported those actions. Laird is captured on tape arguing that Lavelle’s “protective reaction should be viewed liberally.”

Yet even with that knowledge today, clearing Lavelle’s name has remained unfinished business for two former Air Force judge advocates who have dedicated much of the past 15 years to achieving justice in the general’s memory.

In 1972, 28-year-old Air Force Capt. Ed Rodriguez returned from R&R to the 7th Air Force legal office to find his normally bustling shop empty, the staff essentially floored by the sacking of their commander.

Now nearly 80, Rodriguez and another retired Air Force JAG colonel, Col. Gordon Wilder, have compiled a comprehensive case in Lavelle’s favor. The two launched their drive to clear Lavelle’s name in 2008, roughly a year after the White House recordings were released. In the years since, their case has endured a byzantine back-and-forth among the Air Force, the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Senate, and the White House. If Lavelle is ever to be cleared, they need the support of every one of these institutions.

Rodriguez and Gordon have amassed a litany of documentation outlining their complicated case. They argue Lavelle took necessary and legal steps to protect his pilots and aircrews, and lament the failure of past administrations to right a wrong inflicted more than 50 years ago.

“Whenever we speak with someone about the Lavelle case, there’s always a tendency to want to delve into the substantive issues as to whether [he] ordered strikes against North Vietnamese targets outside the rules of engagement, and secondly, whether he ordered the falsification of the records of those strikes,” Rodriguez said. “That case has been substantively won. The record is such now that we can definitively say General Lavelle was within the rules of engagement.”

The Air Force Board for the Correction of Military Records (AFBCMR) ruled twice, in 2009 and 2016, that Lavelle acted within his authority and did not violate orders in ordering the strikes.

But while those rulings have been forwarded in the past to the Pentagon and Senate, the matter has repeatedly been refused or kicked back for further study.

Rodriguez said Lavelle directed those bombing runs under orders conveyed to him through his chain of command.

The Nixon White House transcripts were initially released in 2002 and 2003 and make clear the President badly wanted the radar sites knocked out. Nixon was more acutely concerned about his impending trip to China, however, which would pave the way to formalized relations between the two countries for the first time in 25 years. He wanted all bombing of North Vietnam to cease from Feb. 17 through March 1, 1972, while he was in Beijing, and wanted to avoid any adverse publicity that might cloud his planned Moscow summit in May 1972— the first visit to that capital by a U.S. President since Franklin D. Roosevelt.

In a 2015 white paper published by the National Defense University, author Mark Clodfelter described how Sgt. Lonnie Franks, a U.S. intelligence specialist for the 432nd Tactical Reconnaissance Wing at Udorn Royal Thai Air Base, alleged that pilots falsified reports to claim they were fired upon before taking action against enemy targets. Franks sent his allegation to Sen. Harold E. Hughes, an Iowa Democrat.

Hughes forwarded the information to then-Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. John D. Ryan, who asked the Air Force inspector general to investigate. According to Clodfelter’s account, the IG concluded Lavelle ordered 28 unauthorized missions over a four-month period. Ryan then fired Lavelle and offered him the chance to retire. Lavelle retired, accepted his demotion in title, but kept his four-star retired pay, which was endorsed by a 14-2 vote of the Senate Armed Services Committee.

To support their case, Rodriguez and Wilder say White House transcripts contain numerous conversations that demonstrate Nixon’s commitment, and that of his National Security Adviser, Henry Kissinger, to eliminating the antiaircraft threats.

“Protective reaction should include preventative reaction,” Nixon told Kissinger and Ambassador to South Vietnam Ellsworth Bunker during one conversation on Feb. 3, 1972, two months before Lavelle was fired. “When the radar’s locked on … that’s late to start attacking,” Bunker said.

“I think the way to handle it … is to give them [pilots] a blanket authority,” Kissinger said. “Right now, they [bombers] can hit only when the radar is locked on. And that’s very restrictive because that means the plane which is in trouble also has to fire.”

Nixon added, “I am simply saying that we expand the definition of protective reaction to mean … protective reaction where a SAM [surface-to-air missile] site is concerned. Anything that goes down there, just call it ordinary protective reaction.”

Nixon wanted to avoid public knowledge of such strikes. “I want you to tell [the commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, Army Gen. Creighton] Abrams … that he is to tell the military not to put out extensive briefings with regard to our military activities from now on until we get back from China,” Nixon said.

Later, in another conversation, Nixon said: “Remember I said … if they hit there, go back and hit it again. Go back and do it right. You don’t have to wait till they fire before you fire back.… “Remember I told [Defense Secretary Melvin] Laird that. … Now, Lavelle apparently knew that and received that at some time.”

On April 6, 1972—the a day before Lavelle was officially sacked—Nixon and Kissinger emphasized to Air Force Lt. Gen. John W. Vogt, who would soon succeed Lavelle as 7th Air Force commander, that they wanted more aggressive attacks on enemy strongholds.

“I want you to clearly understand that the performance of the [Air Force] out there has not been, in my view, adequate,” Nixon told Vogt. “It’s been routine and by the numbers, with no imagination.”

Nixon went on: “The thing I want you to do is kick everybody’s ass out there. … We’ve got to go in there and win this operation.”

Rodriguez and Wilder say this direction explicitly change the rules of engagement to make clear that Nixon wanted what Lavelle had been doing in the first place.

In 2009, the AFBCMR cited the tapes in recommending Lavelle’s rank be restored, but the Senate Armed Services Committee balked. Chairman Carl Levin (D-Mich.) and ranking member John McCain (R-Ariz.) wrote to then-Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates in December 2010, saying in their view the board had relied on incomplete data to draw its conclusion.

They argued the Nixon tapes offered insufficient proof and skirted the fact that Lavelle had authorized seven airstrikes between Feb. 17 and March 1, 1972, at the very time when Nixon was in China, counter to the President’s expressed wishes.

“Additional work needs to be done to assemble a complete, historically accurate record regarding Maj. Gen. Lavelle’s authority under the rules of engagement in effect in 1972 to conduct preplanned air- strikes, his culpability for falsified official reports, the justification for his relief from command and ultimate retirement in the grade of major general, and to reconcile apparent factual conflicts,” Levin and McCain stated.

Official Air Force historical records of the war, they asserted, contradicted the board’s conclusion that Lavelle “had received ‘out of channels’ authority to conduct airstrikes in violation of the ROE [rules of engagement], and to conceal that he had done so.”

They also mentioned that Abrams had earlier been ordered not to conduct a strike against the Moc Chau ground control intercept radar on Jan. 5—a mission similar to the one Lavelle authorized days later.

Levin and McCain also noted a contradiction in two of Laird’s statements. While Laird had admitted to authorizing the planned strikes in a 2007 letter to Air Force Magazine, he had written in a 2008 biography that he disagreed with Abrams’ request for authority to make such strikes. These facts needed to be run to ground, they said.

“Finally, the committee believes that the Department [of the Air Force] did not consider sufficiently the importance of the falsified official reports submitted by Maj. Gen. Lavelle’s command,” Levin and McCain wrote.

In June 2011, then-Air Force Secretary Michael B. Donley called for an investigation and independent review of the Lavelle matter. Former FBI Director William H. Webster took charge of that review, leading a staff of military and civilian historians and lawyers.

Donley directed Webster and his team to conduct interviews, take sworn statements, and examine records, focusing particular attention on the concerns expressed by the Senate Armed Services Committee.

“The report will thoroughly address the historical record and analyze Maj. Gen. Lavelle’s authority to conduct preplanned airstrikes under the rules of engagement in effect between November 1971 and March 1972, his culpability for falsified official reports, and the justification for his relief from command and ultimate retirement in the grade of major general,” Donley wrote.

Webster filed his report on May 28, 2015, concluding that Lavelle’s reputation had been wrongfully tarnished. But Webster stopped short of fully exonerating Lavelle, instead recommending that his permanent rank be elevated to lieutenant general, one star short of his four-star status in Vietnam.

Webster concluded the airstrikes in question were in fact “authorized by factors outside of the well-settled interpretation of the published ROE, specifically the implicit and oral approval of General Lavelle’s superiors and President Nixon. But he also determined that while Lavelle was not legally culpable for either the airstrikes or falsified reports, “he nonetheless bears some responsibility for the falsified reports” because he had ordered subordinates not to report “no reaction” and failed to make clear his intent. As a result, Lavelle’s superiors in the Air Force felt he exceeded his authority when he ordered the airstrikes, and “was responsible for the false reporting.”

Rodriguez and Wilder disagree with that conclusion. “Judge Webster, in his report, concluded that Lavelle had the authority from his chain of command to conduct the questioned strikes,” Wilder said. Webster, Rodriguez added, “tried to play Solomon and cut the baby in half. In our opinion, that was a result of Judge Webster’s unfamiliarity with the Air Force records-correction system.”

Rodriguez and Wilder followed up Webster’s report with a second appeal to the AFBCMR. The board took up the case, and responded favorably; in 2016, the AFBCMR recommended Lavelle’s rank be restored to general.

Marine Corps Gen. Joseph F. Dunford, then the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, approved the board’s recommendation in 2018 and forwarded the matter to the Senate, where it languished.

Since then, the case was returned to the Pentagon, where it has been shuffled back and forth between the Office of the Secretary of Defense and the Office of the Secretary of the Air Force. The inhabitants of both offices have changed multiple times over that period. Today, the matter is in the files of Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall, Rodriguez said.

Department of the Air Force spokesperson Laurel Falls said, “The Air Force has put significant time and effort into processing this request over the years with both the Department of Defense and Congress. At this time, there’s not been a resolution on the request.”

Rodriguez and Wilder hope still “to persuade the Department of the Air Force to recommend to the Secretary of Defense that Lavelle be nominated posthumously for advancement back to his wartime grade as general.” Rodriguez said, “If Secretary Kendall were to do that, his would be the fourth such secretarial recommendation.”

“DOD has kind of played pingpong,” Wilder said. “Every time there’s a change in administration, [the department] sends it back to a new Secretary.”

For Wilder and Rodriguez, the case has taken on personal meaning.

“I knew John Lavelle,” Wilder said. “I was an Air Force brat. He was commander of the 17th Air Force in Germany when I was a kid. He used to come out and watch us play football in front of his house.”

Lavelle doesn’t deserve to be remembered as “the one general in U.S. history that refused to obey the orders of the President.”

That history is taught today unfairly, Wilder said, noting also that Lavelle’s case has been used by the military academies as a textbook example of exceeding authority.

“That is so wrong,” Wilder said. “I get emotional and angry just thinking about it.”

For Rodriguez, it is about setting the record straight all these years after his commanding officer was dismissed.

“I was there when it happened,” Rodriguez said. “Of course it was way above my paygrade, and I didn’t understand what was happening when he was removed from command.” But fixing the record is “the right thing to do.”

“Loyalty goes down from the commander to his men, and back up to the commander,” Rodriguez said. “I am showing my loyalty to my commander by continuing to work all these years to exonerate him, and to get his four-star grade back for him.”

Said Wilder: “Everything General Lavelle did was for his people. He didn’t fly these missions—or order these missions—to do anything but protect his Airmen after the conditions in Vietnam had changed such that his pilots were getting killed with no notice, because of the way the radars were added in North Vietnam.”

“The Lavelle family has borne the stigma of having their father cast as a bad guy for 45 years,” Rodriguez said. Lavelle’s children are now in their 70s and 80s. “It’s just gone on too long,” he said. The Vietnam War ended 50 years ago, it’s painful history eased by the passage of time and the forgiveness of many. The time has come, Rodriguez argues, for Lavelle’s war to be ended as well.