New Medal of Honor Museum Plays Down 21st Century Air Force Hero.

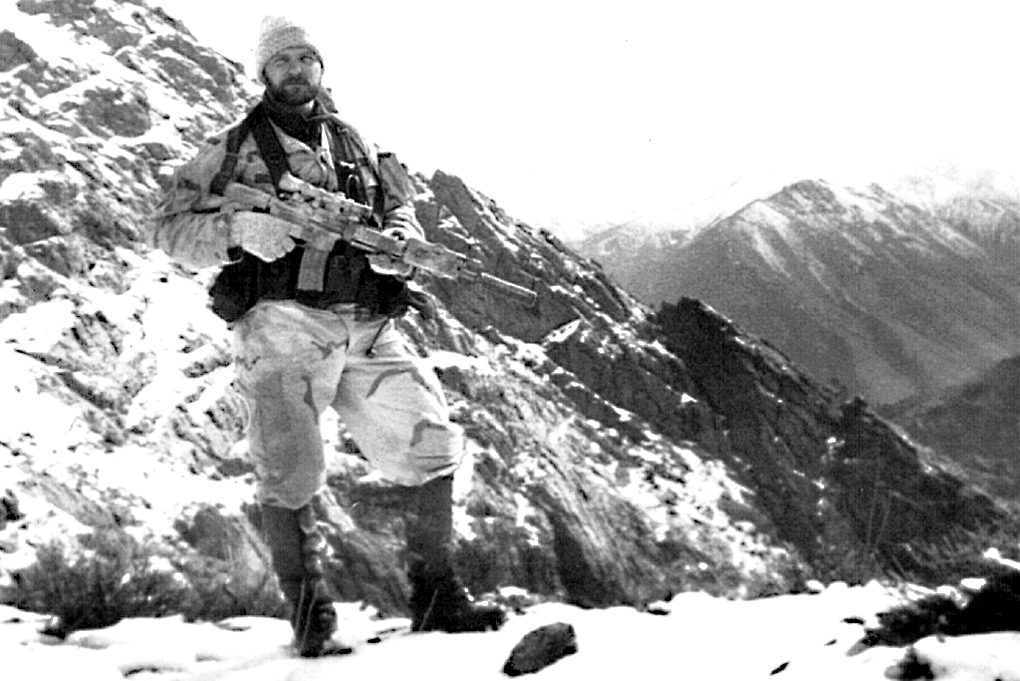

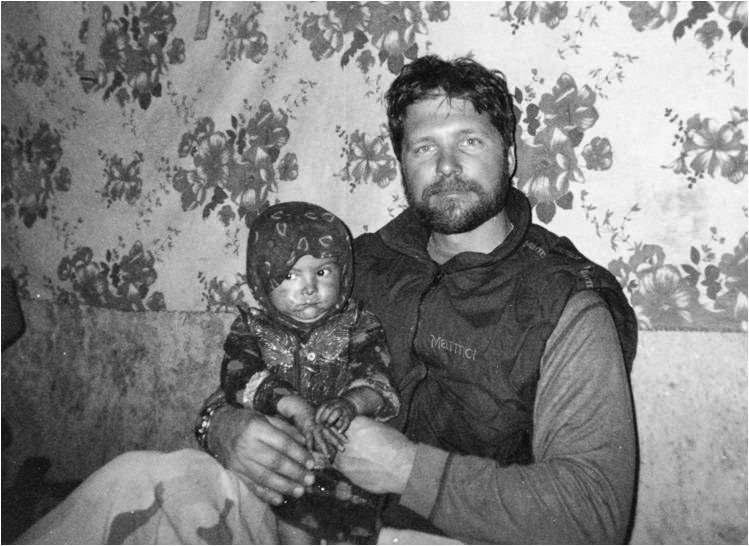

Twenty-three years after his heroic death on a frozen Afghan peak, John Chapman is still fighting against the odds.

Chapman, a combat controller with the 24th Special Tactics Squadron (STS), died March 4, 2002, fighting al-Qaida fighters on top of Takur Ghar Mountain in eastern Afghanistan after the SEAL Team 6 element to which he was attached mistakenly left him for dead when they retreated at night under heavy fire. Now those events are back in the headlines, this time because of decisions at the National Medal of Honor Museum, which opened March 25 in Arlington, Texas.

Chapman is the only Airman to be awarded the Medal of Honor in the 21st century and his award was not made without its own share of controversy. He was originally awarded an Air Force Cross for his efforts that day, although some reviewers wondered even then if he merited a Medal of Honor. It wasn’t until years later that the case was reopened and reviewers used video from a drone overhead that showed Chapman fighting on, alone—after the SEAL team withdrew. Momentum then built to upgrade the award.

But the SEALs resisted efforts to upgrade Chapman’s award. A standoff ensued, broken only after an unusual compromise: Chapman’s award would be upgraded, but so would that of now retired Navy Command Master Chief Britt Slabinski, who led the SEALs off Takur Ghar that day and inadvertently left Chapman to fight and die alone. Slabinski believed Chapman was dead when he evacuated the mountain.

Lori Longfritz, Chapman’s elder sister, says the Medal of Honor Museum led her to believe for more than a year that he would be among 200 Medal recipients singled out at the museum with a personal exhibit. Then in January, just two months before the museum’s opening, she learned that would not in fact be the case. Chapman instead would be included within one of the museum’s feature displays, a timeline showing the history of the Medal of Honor, from its creation during the U.S. Civil War to the present. His distinction: His case represented the first use of video evidence to support a Medal of Honor award.

Longfritz might only have been disappointed that her brother would not be among the featured Medal of Honor recipients honored in dedicated exhibits at the museum; but what really rankled her was that while he was not being honored, Slabinski would get star treatment.

Slabinski turned out to be a member of the museum’s board of directors. The museum’s President and CEO, Chris Cassidy, and two other influential board members were also former SEALs; Slabinski’s wife, meanwhile, is employed by the museum as its associate director of recipients and veterans relations. These revelations made the decision to highlight Slabinski at the apparent expense of Chapman more than disappointing.

ROOTED IN CONTROVERSY

The dispute at the Medal of Honor Museum traces its origins to one of the earliest and most controversial battles of the War on Terror, a failed mission during Operation Anaconda in March 2002 in which U.S. and coalition forces sought to encircle and destroy eastern Afghanistan’s last remaining mass of al-Qaida fighters. The battle took place in the rugged Shahikot Valley.

Ahead of the first wave of heliborne infantry troops descending on the area, three elite U.S. special operations reconnaissance teams—two from Delta Force and one from SEAL Team 6—had audaciously infiltrated behind enemy lines into the high ground surrounding the valley.

Over several days, the teams used their hidden positions to report on enemy locations and to call in airstrikes, thus helping prevent a battlefield disaster. That success captured the attention of SEAL Team 6 officers at Bagram Air Base, about 100 miles north; Team 6 had seen little action so far in Afghanistan, and they were keen to get their operators into the fight.

Lt. Col. Pete Blaber, a veteran of the Army’s Delta Force, had overseen the first three teams’ infiltration. But in a decision with fatal consequences, the SEALs cut Blaber out of the communication loop and made plans to insert a small combat element onto Takur Ghar, the 10,469-foot mountain that was the valley’s dominant terrain feature.

The eight-man unit, a reconnaissance element called Mako 30, was led by Slabinski, and included six SEALs, an Army signals intelligence specialist, and Chapman. The team’s initial plan was to fly to an offset location about 1,300 meters east of the peak and patrol up the slopes in darkness. That way, their night vision goggles and ability to call in airstrikes would give them an advantage should they encounter any enemy.

Then a series of delays out of the SEALs’ control set their plans back. Slabinski asked to delay the infiltration 24 hours, but was overruled by his bosses in Bagram. With less time to maneuver under cover of darkness, Slabinski chose to fly straight to the top of the mountain, violating a golden rule: Never land directly on the spot that you intend to make your observation post.

An AC-130 gunship had flown over the peak hours previously and reported it to be unoccupied, but when the twin-rotor MH-47 Chinook helicopter arrived to deliver Mako 30 atop Takur Ghar, they found that intelligence to be faulty. Al-Qaida fighters were dug in, occupying the peak with machine guns, bunkers dug into the mountain, and a tent. As soon as the helicopter arrived, the al-Qaida fighters started firing on the U.S. forces.

An al-Qaida bullet severed a critical hydraulics hose on the helicopter, and chaos began to unfold. In the few seconds that it took for Slabinski to absorb this new reality, he tried to tell the pilots to abort the mission, to get the team out of there.

But as the Chinook lifted off, one of the SEALs, Petty Officer 1st Class Neil Roberts, either jumped or fell out of the aircraft, dropping 10 feet into thick snow; it is possible Roberts mistook the call to pull away as a directive to disembark the helicopter. Unable to turn around, the pilot, a seasoned member of the Army’s elite 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, steered the stricken helicopter away from the mountaintop as a crew chief hand-pumped cans of hydraulic fluid into the hydraulics system, desperately trying to keep the aircraft airborne. The leak was devastating, however, and the fluid quickly ran dry. The engine failed, and the pilot crash-landed the aircraft at the north end of the valley.

Slabinski, Chapman and the others were desperate to get back to Takur Ghar to rescue Roberts. But with the helicopter too badly damaged to fly, they had to wait. It took 45 minutes for another helicopter to arrive and fly them 8 miles north to the local special ops base at Gardez, where Slabinski, Chapman, and four others boarded a third Chinook for the return trip to the peak.

The Battle Unfolds

Arriving back at Takur Ghar, hovering above the mountaintop, the helicopter and its crew endured a withering hail of fire as the six operators jumped into the snow. The would-be rescuers could not have known it just then, but Roberts was already dead, killed by the al-Qaida fighters about half an hour before.

A Predator drone captured video of the scene with its infrared camera. Slabinski can be seen to stumble as he lands in the snow, while Chapman moves immediately uphill to suppress heavy fire coming from a bunker. Closing to a distance of no more than 10 feet, he kills the two militants in the bunker.

Then machine gun fire bursts from another bunker. Chapman returns fire, but is shot and falls to the ground. Slabinski would later say that he glanced at Chapman and took note: Chapman’s rifle was laying on his chest, its aiming laser rising and falling with his breath. He was still alive. Then another member of the team was badly wounded.

Mako 30 was in danger of being wiped out. With no sign of Roberts, Slabinski knew he had to get his men off the mountain. But where was Chapman? Here is where the story gets murky. Slabinski did not respond to an emailed request for comment for this article, but in 2016 he told this reporter, for an article in The New York Times, that as he and the other SEALs edged off the mountaintop, he crawled over Chapman and determined he was dead.

The overhead footage does not show Slabinski crawling over anyone, but based on all details available, it appears that the body Slabinski thought was Chapman’s was, in fact, the deceased Roberts.

As another of his men was wounded, Slabinski and the rest of Mako 30 retreated off the top of the mountain, taking cover under a rocky overhang. Six hours later, after an arduous movement across a mile of rough terrain, they were picked up by a helicopter.

The Predator, meanwhile, continued to loiter overhead. The intelligence feed proved surprising. Despite Slabinski’s initial account that no U.S. forces remained alive there, the Predator camera captured a gunfight on the mountaintop.

There is only one credible explanation for that firefight: That Chapman had actually survived his initial wound and then fought on alone. The video shows Chapman continuing his one-man stand in the heart of an al-Qaida position for about an hour, killing at least one al-Qaida fighter with well-aimed rifle fire and a second in hand-to-hand combat.

Meanwhile, at Bagram, staff officers at the special ops joint operations center were confused. Communications breakdowns meant they were unaware that two helicopters already had been badly shot up trying to land there. As the first of two Chinooks carrying the quick-reaction force [QRF] approached, Chapman came out from cover, exposing his position, to suppress enemy fire. Hours after first being hit, with possible salvation now only seconds away, Chapman was shot once more, this time fatally.

Again a helicopter was badly damaged, setting the stage for a daylong firefight in which five more U.S. troops would die before the Rangers finally wrested control of the peak from the insurgents.

Discussion began almost immediately that Chapman had done something remarkable, surviving his initial wounds and fighting on alone. In the aftermath of the battle, both Chapman (posthumously) and Slabinski were awarded service crosses for their actions. At least some on Chapman’s medal review board believed the Airman’s valor merited more: a Medal of Honor.

That is where things stood for more than a decade. But in 2016, as part of a larger Defense Department review, then-Air Force Secretary Deborah Lee James initiated a study to determine whether any Air Force awards during the War on Terror deserved to be upgraded to a Medal of Honor. (No Airman had received a Medal of Honor since the Vietnam War.)

Chapman’s Air Force Cross was the obvious candidate.

The Predator as Eyewitness

Requirements for the Medal of Honor are stringent, and until then, eyewitness testimony was necessary. The problem was that no eyewitnesses were on hand as Chapman waged his lonely fight. But there had been witnesses to the Predator feed, and that evidence offered something new: reviewable video of the battle. An Air Force team then combined the Predator footage with video from an AC-130H Spectre gunship, creating a compelling case showing Chapman’s exploits. The service argued that the video was the equivalent of eyewitness testimony, perhaps better even, as memory can be fallible, and that by charging the bunker to kill the two militants inside, then fighting alone on the mountaintop, and finally sacrificing his life to protect the inbound Chinook, Chapman more than met the criteria for the Medal of Honor.

Indeed, retired Lt. Col. Dan Schilling, another 24th STS veteran who was the co-author, with Longfritz, of “Alone at Dawn,” a biography of Chapman, published his version of the video with his own narration that argues that Chapman’s exploits warranted two separate Medals of Honor.

The case for the upgrade ran into pushback almost immediately, however. The SEALs objected to the upgrade, which cast light on their organization’s shortcomings during that mission. The Air Force’s version of events on Takur Ghar necessarily implied that the SEALs mistakenly left behind a living member of their team, Chapman—a finding the Naval Special Warfare Command was unwilling to accept. Led at the time by Rear Adm. Tim Szymanski, who had been one of the officers in the Bagram joint operations center, the command waged an unprecedented campaign against upgrading Chapman’s medal.

After a long and bitter dispute Chapman’s Medal of Honor upgrade was allowed to advance, but only if the Pentagon also upgraded Slabinski’s Navy Cross. The agreement also split Chapman’s citation in two, one part public, the second part classified. This has led to a misunderstanding by some that Chapman earned two awards that day; although, as Schilling points out, the actions, taken separately, each qualified for Medal of Honor recognition, only one medal was awarded.

Each Medal of Honor came separately: President Donald Trump presented Slabinski with his Medal of Honor at a White House ceremony on May 24, 2018. Three months later, on Aug. 22, 2018, at another White House ceremony, Chapman’s widow, Valerie Nessel, accepted his Medal of Honor from Trump on what would have been their 26th wedding anniversary. The following day, Chapman was posthumously promoted to master sergeant.

FIGHT FOR RECOGNITION

Since his death, Chapman’s loudest champion has been his sister, Lori Longfritz.

When Longfritz found out that a National Medal of Honor Museum was being constructed in Texas, she followed its progress closely. In 2022 an acquaintance arranged for her to be put on the email list for biweekly construction updates from the museum’s chief of operations, Darrell Utt. In April 2023, she and other members of her family even held a Zoom meeting with retired Air Force Col. Mike Caldwell, the museum’s director of recipient and executive support, at his invitation, to discuss how the exhibits would be displayed.

In December 2023, she suggested to Utt via email that she visit the construction site with one or more representatives of the 24th STS to discuss artifacts that the unit and Chapman’s family might make available for a Chapman exhibit. He agreed to set up the meeting, and looped in the museum’s curator, Greg Waters. A close reading of the exchanges that follow, which Longfritz shared with Air & Space Forces Magazine, reveals that although no museum official stated that Chapman would have his own exhibit, the museum representatives made no effort to disavow Longfritz of that notion.

An Oct. 5, 2023, contemporaneous email from Longfritz to others in her family indicates that Longfritz understood from Caldwell that her brother would have his own exhibit. “I just got off a call with Col. Caldwell (Ret.) regarding the museum and the displays,” she wrote. “He told me that John’s display will be in a different place/building than Slabinski’s … Col Caldwell said they haven’t quite decided on how each display will be laid out, but did say John’s is special since his MOH is the first with video proof. I’m excited to see how they do it.”

Six weeks later, in a Dec. 20, 2023, email, Waters indicated interest in acquiring artifacts for display: “I would love to learn more about the artifacts that are potentially available that would help us share the John Chapman story with our future museum visitors.” There is no indication that Waters was thinking about a future beyond the 2025 opening of the museum.

Longfritz visited the museum site on Feb. 2, 2024, accompanied by retired Senior Master Sgt. Mike Rizzuto, who had served with Chapman in the 24th STS. “The main reason he was coming is they wanted to be able to offer up any artifacts that the unit had that maybe could be used in the museum,” she said.

After touring the site, Longfritz met with a small group of museum officials in a conference room, she told Air & Space Forces Magazine in February 2025. The group included Waters, Caldwell, and Alexandra Rhue, senior vice president for museum engagement and strategic initiatives, she recalled. Again, she concluded the meeting with the firm impression that the museum planned to give Chapman his own exhibit.

“They actually showed us where they were going to most likely put John’s exhibit,” she said. Waters told her that he and Caldwell would travel to Colorado to meet with Terry Chapman, the mother of Chapman and Longfritz, for whom travel is difficult due to medical issues, according to Longfritz. (In a March 11, 2024, email to Longfritz, Waters wrote, in answer to a query from Longfritz about why her mother hadn’t heard from him: “I haven’t reached out to your mom yet as I’m waiting to coordinate with Mike Caldwell’s schedule.”)

During the meeting in the conference room, Longfritz said, she also “called out the elephant in the room,” asking whether the museum planned to place her brother’s exhibit beside Slabinski’s. “They said, ‘The exhibits will not be together,’” which Longfritz understood to mean that Chapman and Slabinski would each have their own exhibit. For Longfritz, this was key, because she held Slabinski partially responsible for fighting against Chapman’s award upgrade: “I wanted to make damn sure that Slabinski had zero to do with John’s exhibit.” Museum officials assured her that he would not, she said.

A Feb. 5, 2024, email from Longfritz to Waters, Utt, Rhue and Caldwell expressed surprise at learning that Slabinski had a seat on the museum foundation’s board. “How is someone who actively participated in several attempts at squashing another man’s Medal of Honor … the man who saved his life and for whom, thankfully, there was video evidence … allowed on the board?” she wrote. “I’m not looking for an answer; it’s just a headshaker for me.”

In a March 11, 2024, email to Utt, Longfritz inquired whether her earlier comments about Slabinski had upset museum officials. She stated again that she was concerned about any “potential influence on the board” that Slabinski might wield. “John isn’t here to ensure his story is correctly and properly told,” she wrote. “I am; It’s my duty.”

Utt’s reply sought to set Longfritz’s mind at ease. He told her he’d passed her concerns on to Cassidy, the museum president and CEO. “Rest assured, your dedication to ensuring accurate representation is noted and extremely valued,” Utt wrote.

Months later, in November 2024, Longfritz discovered that the museum would not mount an exhibit dedicated to her brother. “Somebody reached out to me and said, ‘Hey, I spoke to someone within the museum and was told that you were misled on your tour back in February,’” she recalled in the interview.

Longfritz was unsure whether to trust this new information; it seemed so at variance with what museum officials had told her. But on Jan. 6, in an email from Waters to Terry Chapman, the family learned that the museum’s only references to John Chapman’s heroism would be a photo portrait in the introduction video that visitors see as they enter the museum and “the timeline of the history of the Medal of Honor,” which would feature the overhead footage. “We initially thought that we could include a few small artifacts related to his story as well,” Waters wrote, “but we later realized that this wasn’t possible due to space constraints.”

Later that day, Rhue sent a similar email to Longfritz. “Of the over 3,500 Medal of Honor Recipient stories, we are able to feature about 200 in the inaugural exhibit,” Rhue wrote. “Through the next few decades, we will be rotating exhibits and expanding on stories. I look forward to sharing more of John’s story.”

Longfritz asked in follow-up emails whether Slabinski would be among the 200 featured exhibits. Rhue confirmed that he would.

Longfritz was irate. Not only did the SEALs appear to have sought to diminish her brother’s heroism, but the museum had apparently knowingly allowed her to believe that John Chapman would have his own exhibit. She had thus spread that word with friends and family and encouraged them to travel to the opening. The museum didn’t reveal the facts until directly questioned.

“They told us that there would be an exhibit. … They knew that there was going to be lots of family and friends going, expecting to see a beautiful exhibit for John,” Longfritz said. “And only at that point in time, while we’re standing there in the museum, was when we would find out that there wasn’t one. … They were willing to let my mother, 83 years old and on oxygen, figure out how to get to Texas to see her son in a museum exhibit, only then to find out that there wasn’t one. Why? What motivates somebody to do that to a family?”

Air & Space Forces Magazine arranged an interview with Caldwell to ask him about these events, but his bosses at the museum canceled the call and referred the magazine to Seven Letter, a strategic communications firm engaged by the museum. A spokesperson, Amber McDonald, declined to provide a museum official for an interview, instead emailing a statement from Cassidy that had been posted online in January. McDonald was provided a list of questions, but she did not reply.

MUSEUM INSIDER’S ACCOUNT

According to a former official at the museum, there was never any intent to mount a Chapman display.

Although Cassidy’s Jan. 31 statement says that the museum did not make its final decisions on exhibits until March 2024, the former museum official who spoke with Air & Space Forces Magazine on condition of anonymity said the decision on Chapman’s exhibit had already been made when Caldwell, Rhue, and Waters met with Longfritz in February 2024.

“That decision was made in late 2022/early 2023 … well, well, well before” Longfritz’s visit, the former museum official said. “They placated her, they lied to her, and said, ‘Oh yeah, maybe we can get some artifacts,’ knowing they were not going to use any of those artifacts.”

The December 2018 addition of Slabinski to the museum’s board ensured that his version of the Takur Ghar battle would take precedence, according to the former museum official. With Cassidy at the helm and retired SEALs Mike Hayes and Chris Sambar also on the board, the SEAL influence won out.

“There’s a connection there,” said the former museum official. “It all had to do with keeping Britt [Slabinski] happy.”

The board’s collective feeling was that giving Chapman an exhibit ran the risk of embarrassing Slabinski, according to the former museum official, who characterized the civilian board members’ view of Slabinski and other Medal of Honor recipients as akin to hero worship.

“The people on the board, they eat up the Medal of Honor recipients,” the former museum official said. “They weren’t going to [give Chapman an exhibit] and take something away from Britt, especially when he does so much for the foundation and his wife works for us.”

Yet there was another reason why the board was keen to stay on Slabinski’s good side, according to the former museum official. In 2023, Slabinski ran for president of the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, a completely different organization, but one which has its own small museum on the World War II aircraft carrier USS Yorktown at Patriots Point, S.C.

The society did not have a good relationship with the National Medal of Honor Museum under its previous president, retired Army Master Sgt. Leroy Petry, the former museum official said. “They hated us,” the official asserted. “We did not get along.”

Medal of Honor recipient and Army Lt. Col. Will Swenson was already on both boards, but in 2023 three other Medal of Honor recipients on the National Medal of Honor Museum’s board successfully ran for election to the society’s board, which stipulates members must have received the Medal of Honor. That meant that four of the museum’s five Medal of Honor recipient board members were now on the society’s nine-member board, including the president (Slabinski) and vice president (Swenson).

“We knew that he was going to be going up against Leroy Petry at the next Congressional Medal of Honor Society [election],” said the former museum official, adding that leaders at the National Medal of Honor Museum were hoping that if Slabinski won, they would get more access to the society’s artifacts. As a result, “there was a lot that went into … making Britt happy.”

After Slabinski’s election, “Greg Waters and Alex Rhue went to Patriots Point, S.C., to look at all of their exhibits, to see what was what, what’s the value, is there anything that we need,” said the former museum official, who did not know whether the trip proved fruitful.

THE FIGHT CONTINUES

Museum leaders understood the challenge but decided on a strategy of “kicking the can down the road” when it came to delivering the hard truth to Chapman’s family. Several individuals warned them that they were courting controversy by not giving Chapman his own exhibit, and Cassidy and Rhue were told repeatedly that “there’s a lot of sensitivity in the special operations community about this,” the former museum official said. But those warnings fell “on deaf ears—over and over and over again,” the former museum official added.

In January 2025, the issue exploded into public view. Longfritz voiced her frustrations in a Jan. 9 Facebook post that caught the attention of military-oriented publications and special operations-focused outlets in particular. In his podcast, “The After-Action Report,” Seth Hettena called the situation “Stolen Valor at the Medal of Honor Museum.” Dave Parke, a former Ranger who co-hosts “The Team House” podcast, launched an online petition that, by early March, had garnered 25,000 signatures.

“We ask the National Medal of Honor Museum to revise their decision to not represent John Chapman’s sacrifice and deeds amongst their exhibits,” the statement accompanying the petition says. “The Museum’s choice to honor Britt Slabinsky [sic] without acknowledging John Chapman appears influenced by politics and seems like an extension of the Naval Special Warfare’s efforts to diminish Chapman’s contributions.”

The blowback caught the museum’s executives “flatfooted,” said the former museum official. “They were shocked, and I think that’s why they were so just deathly quiet initially.”

After weeks of criticism, the museum issued its Jan. 31 statement, in which Cassidy stated that the “recipient stories” that the museum chose to highlight “are those for whom we were able to work with family members or other academic institutions to be entrusted with a significant number of artifacts and unique personal items which can be displayed to help bring their story to life.”

The statement ignored evidence shared with Air & Space Forces Magazine that makes it clear that both the Chapman family and the 24th STS reached out repeatedly to the museum to discuss what artifacts the museum might want for a Chapman display—but neither the museum nor its communications agency answered our follow-up questions.

Cassidy’s defense centers on the museum’s timeline feature and its inclusion of a segment of the video that underpinned the upgrade of Chapman’s Air Force Cross to the Medal of Honor. “The video … represents a turning point in the traditional verification criteria for how Medals of Honor are awarded and is part of the Museum’s permanent exhibit which will not be subject to our planned regular rotation,” Cassidy wrote. “This means Master Sergeant Chapman will remain a featured recipient for the foreseeable future.”

But the former museum official said the Chapman video will be only a “very small” piece, one “that’s probably going to get overlooked” by many visitors. By contrast, “Britt Slabinski is getting one of the main exhibits, like [notable Army heroes] Audie Murphy and Alvin York [are] getting.”

All this controversy was avoidable, the former museum official said: “This is a self-inflicted wound. They didn’t think anybody was going to call them out on it, and here they are. They got called out.”

Sean D. Naylor is the author of “Not a Good Day to Die: The Untold Story of Operation Anaconda” and “Relentless Strike: The Secret History of Joint Special Operations Command.” He covered Operation Anaconda from the Shahikot Valley for Army Times as an embedded reporter. He now edits and writes for The High Side, an online publication he co-founded with Jack Murphy dedicated to investigative journalism on national security.