USAF exercises take on a Pacific flavor, as Red Flag and Mobility Guardian ready the force for a new kind of conflict.

Over the Pacific Ocean

An F-35 pulled up to a KC-135 at 24,000 feet off the coast of California to take on a few thousand pounds of fuel before peeling right in training area W-291.

The fight was on and so was a new chapter of Red Flag.

Established in 1975 to better prepare Air Force pilots due to the lessons from Vietnam, Red Flag has been conducted at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada for decades. But with the Pentagon’s new focus on China, the exercise has been changing, including by expanding over the Pacific.

“This is what we’ve been told to do, which is prioritize the pacing challenge of China,” said Maj. Gen. Case Cunningham, the head of the U.S. Air Force Warfare Center, which runs Red Flag, as jets roared over his office.

In addition to the novelty of flying over water, the February exercise featured forces from some of America’s closest allies, Australia and the U.K., as well as Marine F-35 fighters, requiring the Air Force to “speak Navy,” noted Col. Jared Hutchinson, then-commander of the 414th Combat Training Squadron (CTS), which runs Red Flag.

The February exercise, Red Flag 23-1, was not the first time the Warfare Center, the Air Force’s high-end combat training school, has sent aircraft missions over the ocean. But it was a first for Red Flag, which has broadened its training areas to include the range west of the Baja Peninsula south of San Diego.

“This is a small step forward,” Hutchinson said the day before the inaugural February maritime sorties. “Make no mistake, the logistical challenges are real, the tyranny of distance. You can’t just hand wave solving that problem.”

Tackling New Challenges

Red Flag’s expanded reach is part of a broader transformation underway in the Air Force’s training establishment. In 2018, the Pentagon’s National Defense Strategy (NDS) said that great power competition with China was the main focus following decades of counter-insurgency operations in the Middle East and South Asia.

Other exercises are also taking on a Pacific flavor and increasingly including international and joint force partners. Air Mobility Command’s Mobility Guardian ’23 used to be a domestic exercise. This year’s edition spread out across the Pacific.

The Air Force is using these exercises to drill Airmen in new operational concepts, such as agile combat employment, which emphasizes the ability to work from dispersed and sometimes austere locations.

At Nellis, the Pentagon’s new priority is apparent from the photos of Chinese aircraft, including a J-20 stealth fighter, on Cunningham’s desk, which are positioned next to quotes from Air Force Chief of Staff Charles Q. Brown Jr., and Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall on the importance of modernizing to deter China.

“Here’s why it matters: because there’s lots of people that want the Warfare Center to do any number of things,” Cunningham said of the NDS. “We do not have the time, the resources, or the people to get at every challenge and against every single adversary that we could potentially face.”

To prepare for the new challenge, the Air Force’s training establishment has adjusted too. A map of the Pacific is posted on the wall of Cunningham’s office next to maps of the Nevada Test and Training Range, the Utah Test and Training Range, and the R-2508 Complex—a training range used by Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, National Training Center, and Edwards Air Force Base, Calif.—and also the training area off the California coast.

“The airspace has to get bigger,” Cunningham said. “The capabilities that we’re replicating get more complex.”

The new emphasis on the Pacific is not the only reason to expand the scope of the training. Advancing technology is another factor. The fifth-generation F-35 Lightning II jets can sense over longer distances and can operate when a wingman might not even be in sight.

“You are actually beyond the visual range,” Cunningham explained.

Flying over the Pacific has other advantages, including fewer constraints than exercises conducted over the United States and the realism of flying over a blue floor.

“There are less restrictions on our airspace usage there,” Cunningham said. “We’re pulling these together to provide the capability to extend the fight.”

Mobility Guardian

AMC moved its biennial signature exercise from the continental U.S. to the Pacific this year, bringing together some 70 aircraft and 3,000 personnel to operate at bases in Hawaii, Guam, Australia, and Japan.

“If you do an exercise in the continental United States, you don’t have to go through that in reality, you just have to simulate it,” said Maj. Gen. Darren Cole, Air Mobility Command’s director of operations, strategic deterrence, and nuclear integration and exercise director of this year’s Mobility Guardian.

AMC’s boss, Gen. Mike Minihan, has been one of the service’s most ardent proponents for meeting the challenge from Beijing, going so far as to say war might erupt in 2025. Minihan has been blunt saying the U.S. military is not currently postured well enough to fight inside the so-called first island chain of the Pacific, the string of islands running from the Japanese archipelago to the Philippines. So, Mobility Guardian was designed to put the logistics of operating over the vast Pacific to the test.

“If you want to hit the easy button, you don’t do that,” Cole said.

The Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, and the Space Force have also been practicing how they would operate in the Pacific this summer in joint and multinational drills. Allies see the virtue of Pacific operations as well.

“The U.K., from a government-down level, has started to pivot over into looking into that region of the world,” Air Commodore Howard Edwards, Royal Air Force Combat Air Force commander, said during Red Flag’s February iteration, which featured RAF Typhoon fighters and Voyager refueling aircraft.

The RAF also brought those aircraft to Mobility Guardian. Emphasizing the “tyranny of distance” in U.S. parlance, a British A400 airlifter flew over 20 straight hours to get to the Pacific from the U.K.

“We need to be able to operate and fight in that environment, and we haven’t traditionally done so certainly in a very, very long time,” Edwards said of the Pacific.

But Red Flag is the Air Force’s premier training event, with lessons that will ripple through the service.

Know Your Enemy

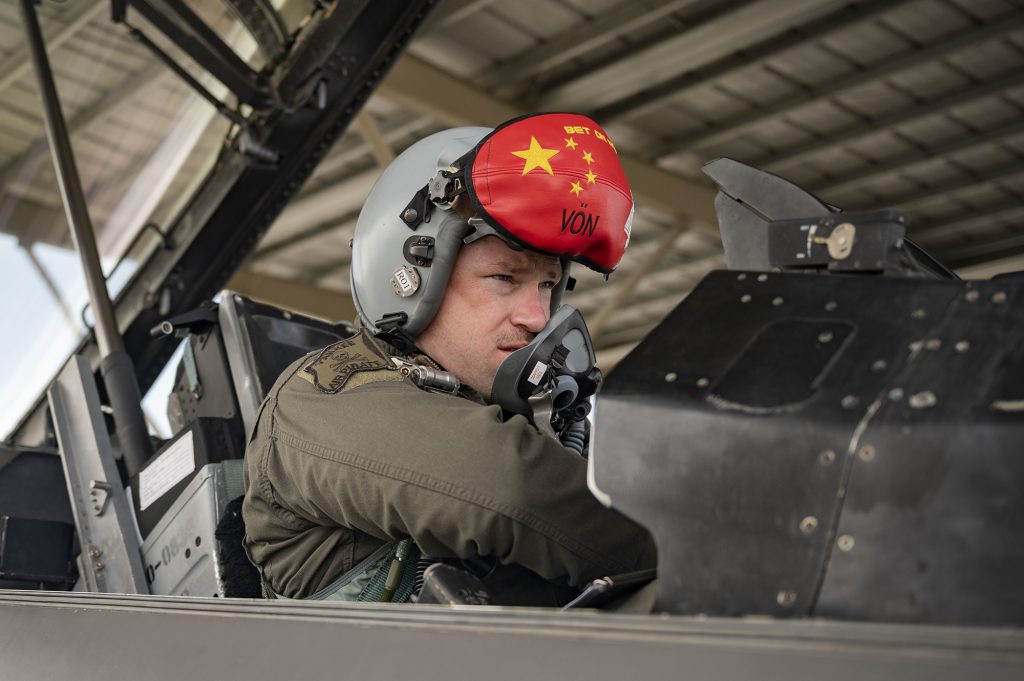

The task of simulating the adversary in Red Flag falls to the “Red” aggressor pilots who mimic tactics U.S. foes might carry out against “Blue” allied forces.

To replicate the threat presented by potential foes, the Nellis 64th Aggressor Squadron of F-16s and 65th Aggressor Squadron of F-35s have dedicated subject-matter experts in the adversaries’ doctrine and tactics, down to the capabilities of specific missiles and aircraft.

The use of F-35s is another recent step toward making the enemy threat more realistic, and the aggressors are also looking at ways to improve their capability through the use of other systems, such as upping their electronic warfare capabilities. To drive the training home, the aggressors are quick to respond if the Blue Force makes mistakes.

“You have to be willing to punish a tactical error to provide a lesson there,” said Lt. Col. Brandon Nauta, an F-35 pilot who commands the 65th Aggressor Squadron.

“We have a mantra here in the aggressor nation. It’s called: Know, Teach, Replicate. We’re constantly studying our enemies,” added Lt. Col. Chris Finkenstadt, who led the 64th Aggressor Squadron before relinquishing command in June. “Day One, you’d like to punch Blue in the face to make them bloody. The best part is, there are times where we get lost in the shuffle during a fight and that’s when we’re able to create a lot of lessons learned.”

Typically conducted three times a year, Red Flag-Nellis has iterations with so-called Five Eyes partners with which the U.S. shares intelligence, a broader international exercise, and a U.S.-only mission.

“I think ACC has done a really good job at shifting our focus and our priorities,” said 1st Lt. Kassidi Nudd, an intelligence officer with 355th Operations Support Squadron at Davis–Monthan Air Force Base, Ariz., who is a veteran of multiple Red Flags and works with Blue pilots. “We’re hitting our books, and we’re doing analysis on the daily so that way, when we come here to Red flag, it’s not new information.”

On the February mission, three KC-135s lumbered down the runway, taking off seconds after each other. For now, the present-day fight still requires some of the Air Force’s tried and true assets, including the tankers that were first produced during the Eisenhower administration.

Each day, Red Flag usually flies two missions: one during the day and one at night. To simulate the foe, the two aggressor squadrons are complemented by simulated surface to threats on the ranges. During the daytime mission, things seemed to go well for some of the Blue pilots.

“Blue participants will be tasked to defend five critical assets for 90 minutes. They’ll also be tasked to go destroy 10 to 15 of the enemy’s critical assets every training period,” Hutchinson said of Red Flag 23-1. “They’ll be tasked to destroy the enemy’s simulated integrated air defense system every time that we go out there. And they’ll also be tasked to fight the most advanced Chinese air threats that are available every single time they go up.”

Air & Space Forces Magazine had a view of training from one of the tankers that was operating over the Pacific, Gulf 07. As the exercise unfolded, an aggressor F-16 hooked up with the tanker only to return within the hour. The Red F-16 had been “killed,” but to keep the exercise going needed to get back into the fight again.

By the time Gulf 07 landed back at Nellis six hours later, the sky was dark, but the skies were still busy as the radio buzzed with call signs of “Raptor” and “Janet” flights—the latter belonging to a government airline that serves the Nevada Test and Training Range and the former assigned to Blue F-22s.

For all of its intensity, the Blue team has also been careful not to display all its capabilities and tactics out in the open, conscious that they might be monitored by adversary satellites or other forms of observation.

“We inject virtual tracks to replicate other capabilities that we would have—more exquisite capabilities that may trigger the adversary to do something or react a certain way,” Hutchinson said cryptically. “And we obviously don’t fly that kind of stuff airborne.”

One platform that participated in Red Flag from the ground was the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber, which was on a safety pause at the time due to a mishap in December 2022. Air Force officials declined to say what missions the crews had been planning to fly. But B-2 personnel at Nellis participated in the training and had “superior performers at that flag for mission planning and intelligence gathering,” according to Maj. Gen. Andrew Gebara, then-commander of the 8th Air Force, which controls the nation’s strategic bomber fleet.

Pilots say the training has been challenging.

“The threat, it’s been evolving, and it’s about training to a much more dangerous threat than we have been in the past several years, because that’s where we’re going,” said Capt. Jared Helm, a new F-22 pilot from the 94th Fighter Squadron who experienced his first Red Flag in February.

“There’s going to be something every single time you fly that will make you scratch your head.”

The February training, with around 3,000 personnel, was followed in July and August by exercises that were heavy integrated with U.S. Navy. All told, Red Flag’s summer iteration brought together more than 2,000 Air Force, Space Force, Marine Corps, Navy, and Air National Guard personnel, who operated out of Nellis as well as bases in Southern California and Navy facilities.

The focus was on “realistic scenarios,” according to the 414th CTS, including maritime air-to-air and air-to-surface combat, and working command and control among the diverse participants—all necessary components of possible fight with China.

“The best way to put it is that we put together air-to-air, air-to-surface, and [command and control] in an environment that provided significantly longer distances than in our typical overland scenarios,” said Col. Eric Winterbottom, who took over command of the 414th CTS from Hutchinson in June. “From an exercise management perspective, this applies to running the scenario and collecting data for the debrief. From the execution perspective the distances affect the pacing, communications, fuel planning, and command and control.”

At the end of it all, everyone is on the same side.

“You land and really the initial part of the debrief as a big whole Red Flag group is all about reconstructing the fight in a way that makes sense to everyone that was involved,” Helm said.

“Secrets kept are not constructive,” he added. “We’ll go through and we’ll watch what happened. What we did, who shot who, and at what time.”

Winterbottom noted that this year’s missions were just a preview of what was to come.

“As the new commander, my priority for future Red Flag exercises is to ensure realism and relevance,” Winterbottom said in August. “Red Flag will continue to expand into long-range, dispersed, joint and coalition, peer contested training scenarios.”