The Need for a Cost-Effective PGM Mix for

Great Power Conflict

After decades of deferred and canceled modernization programs, the Air Force’s lead over peer competitors is eroding and its forces are undersized for its operational tasks. At the same time, the Air Force’s budget, which has long been less than the Army’s and Navy’s, is under stress. The Air Force must make smart choices if it is to maximize its future combat power. One of its most critical choices will be the strategy it adopts for developing a precision-guided munitions (PGM) inventory suitable for peer conflict. The Air Force must balance the range, size, speed, survivability, and capacity of its PGM inventory if it is to maintain a long-range strike advantage over China and Russia. This will require the Air Force to develop a family of affordable next-generation, mid-range—50 to 250 nautical miles—PGMs that can be delivered by its stealth aircraft to maximize the capacity and cost effectiveness of its future strike operations.

The Air Force needs to develop a next-generation family of affordable precision-guided munitions with ranges of 50 to 250 nautical miles.

Most defense experts correctly point to the need for the Air Force to field new stealth aircraft to keep pace with China and Russia, yet forget that 5th-generation F-35 fighters and B-21 stealth bombers also give America’s theater commanders another advantage—the ability to penetrate contested areas and conduct “stand-in” strikes that kill multiple targets per sortie. The ability to penetrate and release PGMs closer to targets allows stealth aircraft to carry large payloads of smaller munitions—smaller because the PGMs may not need powerplants and other capabilities required to fly long ranges after launch.

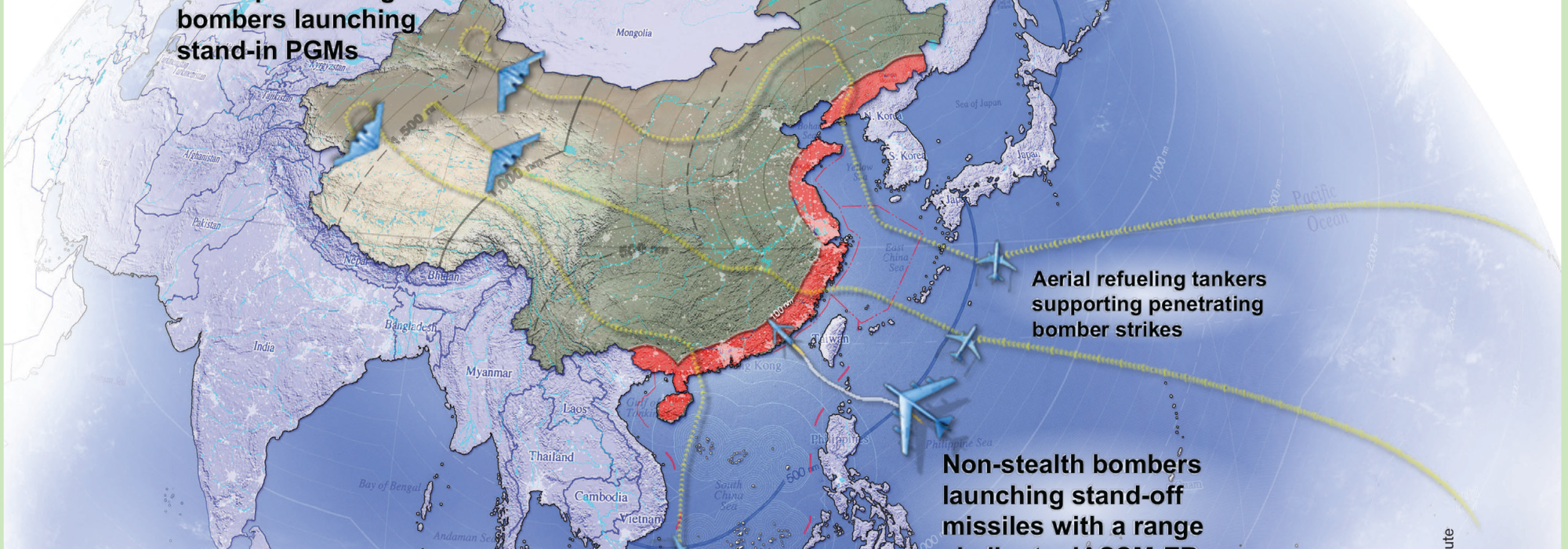

For instance, a penetrating bomber like the B-2 has the internal capacity to carry up to 48 notional stand-in weapons that are sized to have a range of 50-150 nm in its two internal weapons bays, while non-stealth B-52s can carry up to 20 larger long-range JASSM-ER cruise missiles internally and externally. That’s up to 48 targets per penetrating B-2 sortie compared to 20 targets for a non-stealth B-52, which must strike into contested areas from stand-off ranges of 500 nautical miles or more.

Standoff strikes require weapons that have more costly features like engines, fuel, guidance systems, and seekers. A powered subsonic JASSM-ER costs about $1.1 million—six times the cost of a mid-range weapon like the Small Diameter Bomb II (SDB II), a 250-pound unpowered guided bomb designed to glide to its target. Hypersonic (Mach 5-plus) weapons now in development are even more costly, like the Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC) which could cost $3-4 million each. Cost is critical because DOD must buy enough PGMs to strike 100,000 or more aimpoints during a campaign against China or Russia. (For contrast, U.S. air forces attacked approximately 40,000 Iraqi aimpoints during Operation Desert Storm in 1991, a far smaller and less capable adversary).

The maxim “you go to war with the forces you have” applies to munitions as well as aircraft. Today’s force packs legacy munitions that are vulnerable to enemy defenses, ineffective against some types of anticipated targets, or are simply too few in number to be effective. This will not produce victory in a peer conflict. Most air-to-surface munitions in DOD’s current inventory were designed to attack militaries with weak air defenses, but conflicts with peer adversaries equipped with sophisticated integrated air defense systems (IADS) will require more advanced weapons. Addressing these shortfalls cannot wait because the time needed to develop new, advanced PGMs and to surge PGM production is too great to respond to a crisis.

In addition to acquiring 5th-generation F-35 fighters and B-21 stealth bombers that can penetrate advanced IADS, the Air Force needs a new generation of weapons to match. Gen. Mark D. Kelly, head of Air Combat Command, has said his service will not have a true fifth-generation force until its “fifth-gen fighters have fifth-gen weapons and fifth-gen sensing.” Putting today’s third-generation PGMs on the Air Force’s stealth F-35s, F-22s, B-2s, and future B-21s will greatly limit their combat effectiveness.

Although DOD is now developing multiple new precision munitions, many of these efforts are focused on very long-range weapons to equip non-stealth aircraft for standoff attacks beyond the reach of an enemy’s air and missile defenses. These very-long-range standoff munitions can cost millions of dollars each, however, and may not be effective against mobile targets like missile transporter-erector-launchers that can quickly change their locations or targets sheltered in hardened facilities. Designing weapons to fly long distances also increases their cost, since they must have engines, fuel, multiple guidance systems, and possibly seekers to precisely guide their warheads to designated aimpoints.

Looking Back

Thirty years ago, U.S. air forces equipped with a new generation of guided weapons inflicted a stunning defeat on Iraqi forces that had invaded Kuwait. No other military could match the strike capabilities the Air Force brought to the fight during Operation Desert Storm. Today, however, those same air-to-surface PGMs are increasingly unsuitable for operations against peer militaries and even some more advanced regional adversaries. How did this occur?

By 1990, investments in precision guidance technologies, stealth aircraft, and new sensors were swinging the offensive-defensive pendulum in favor of U.S. strike forces. This came about because the Air Force developed both next-generation aircraft and munitions to gain the range, speed, survivability, and lethality it needed to overcome Cold War-era air defenses and attack targets with precision. After the Soviet Union collapsed, DOD shifted its focus to regional contingency operations instead of global conflict with a peer military. DOD’s 1993 Bottom-Up Review determined aggression by lesser adversaries like Iraq and North Korea were the new primary threat to the United States’ global security interests. Because these regional adversaries were largely equipped with antiquated air defenses and lacked the training needed to operate them effectively, DOD curtailed or ended programs intended to produce new stealth aircraft and munitions for contested environments. Over the next 15 years, DOD decided to buy only 21 of the Air Force’s required 132 B-2 stealth bombers, 187 of the required 750 F-22 stealth fighters, and 460 of the originally planned 1,460 stealth Advanced Cruise Missiles. DOD also canceled SRAM II and TSSAM procurement and reduced its capacity to suppress enemy air defenses by retiring the USAF’s F-4G and EF-111 fighters.

DOD’s 1993 Bottom-Up Review also called for developing new “smart” precision-guided anti-armor munitions to defeat the mechanized forces of North Korea and Iraq, and “all-weather” PGMs like JDAMs following lessons from Desert Storm that showed weather, dust, and smoke could degrade the effectiveness of laser-guided air-to-ground weapons. Non-stealth JDAMs use the Global Positioning System to accurately strike targets in all weather conditions and can reach targets up to 15 nautical miles from their release points. At a cost of $25,000 to $45,000 each, they became the signature air-to-surface PGM of the post-Cold War era.

PGM of the post-Cold War era

Over the past three decades, DOD has demonstrated an enduring bias in favor of lower-cost direct attack munitions. For example, during Operation Allied Force in 1999, coalition forces launched 28,018 direct attack munitions, 743 HARMs, and 278 cruise missiles. Likewise, in the Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom air campaigns, coalition forces expended 50,213 direct attack munitions, 1,012 cruise missiles, and 408 HARMs. Overall, 97% of the air-to-ground munitions in these air campaigns were direct attack munitions. From 2004 through 2019, U.S. and coalition partner aircraft delivered about 176,000 munitions on counterterror and counterinsurgency targets operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria—almost all of them JDAMs and direct attack Hellfire missiles.

Now, however, the precision strike offensive-defensive balance is once again shifting, making these legacy weapons far less suitable for the kinds of conflicts anticipated in the future.

The need For a Different PGM Mix

China and Russia’s modernized militaries are far larger and more technologically capable than any the United States has faced in recent decades. Both have advanced weapon systems to deny freedom of action in the air, sea, space, cyberspace, and electromagnetic spectrum (EMS). Great geographic distances in the Indo-Pacific and other theaters add to the complexity of precision strike operations.

Overcoming these challenges requires strike aircraft with range to attack targets anywhere in China and Russia, 5th- generation stealth to survive in contested environments, and the capacity to carry large payloads of munitions, sensors, and other mission systems needed to find and attack mobile/relocatable targets.

In addition to acquiring F-35 fighters and B-21 bombers, the Air Force needs to create an inventory of air-to-surface PGMs that is designed and sized for peer conflict. Rebalancing the Air Force’s PGM mix in favor of a family of next-generation, mid-range PGMs for stand-in strikes is the most achievable means for building up its capacity to take on peer competitors in a sustained fight. These weapons would complement the capabilities of the USAF’s 5th-generation fighters and bombers, improve the Air Force’s ability to defeat challenging mobile, hardened, and deeply buried targets, and will be affordable enough to procure at the scale required by theater commanders.

LONG-RANGE STRIKE

U.S. theater commanders must be able to strike tens of thousands of targets, including adversaries’ airfields, ports, command and control complexes, ballistic missile fields, and critical military industrial facilities, whether they are located along the peripheries of those countries or deep in their interiors. The USAF’s fighter force, however, largely consists of non-stealth aircraft that cannot survive in contested areas. The same is true of the small USAF bomber force, which now consists of 76 non-stealth B-52s, 44 non-stealth B-1s, and only 20 penetrating stealth B-2s. Most of the USAF’s non-stealth fighters and bombers are therefore highly dependent on long-range standoff PGMs to remain survivable. This imposes significant operational limitations. For instance, cruise missiles launched by non-stealth bombers standing off at 500 to 800 nm from land based IADS will only be able can only reach a fraction of potential Chinese military targets, leaving anti-satellite weapons, ballistic missile units, and command and control facilities located deep in China’s interior to be attacked by other means. And while 5th-generation fighters can penetrate contested areas, because they are range limited they too must use long-range weapons. However, stealth bombers carrying mid-range, stand-in weapons could accomplish this mission, penetrating defenses and reaching targets anywhere in China; moreover, their ability to attack from unexpected directions would greatly complicate an adversary’s air defense challenges..

PGMS MUST BE SURVIVABLE

Unlike the defenses U.S. air forces faced in the 1990s and 2000s, Russian and Chinese IADS can deny access to 4th- generation non-stealth aircraft and are increasingly effective against individual PGMs such as non-stealth, sub-sonic cruise missiles.

Russia’s S-300V (SA-12), S-300PMU-1/2 (SA-20A/B) and S-400 (SA-21) all use self-propelled vehicles for their components, so they may deploy or stow within minutes. New phased-array radars are jam-resistant, and Russia’s latest surface-to-air missiles include active electronically steered array (AESA) radars able to track multiple targets simultaneously. Some SAM system variants feature radars that operate in lower frequency bands to improve capability against stealth aircraft. China has also fielded Russian-made S-300 and S-400s and produced derivative systems like the long-range HQ-9. Networking allows radars to work collaboratively across a range of spectrums and enables long-range and short-range SAMs to receive target data from multiple sensors operating in all domains.

Another major difference between air defenses of the 1990s and IADS of today is the proliferation of systems capable of engaging incoming cruise missiles and other guided munitions. These defenses include Russia’s SA-15 (Tor), SA-19 (Tunguska), and SA-22 (Pantsir) mobile SAMs that can target low-flying aircraft, cruise missiles, anti-radiation missiles, and bombs. China has developed its own variant of the Tor known as the HQ-17, and an FK-1000 short-range “point defense” system that resembles the Pantsir. These short-range weapons are fully integrated with electronic warfare systems and longer-range SAMs.

To counter these threats, the USAF might have to revert to a multiple sorties per target strike strategy, instead of striking multiple targets per sortie. The problem is that today’s smaller Air Force is not sized to support that costly approach.

Another approach is to develop hypersonic weapons that are more difficult for air defenses to intercept. DOD is developing hypersonic weapons to strike time-sensitive targets over long ranges in contested areas, but the size of these weapons means fighters and bombers will carry fewer of them per sortie. Some might even be so large that they can only be carried externally by bomber aircraft, precluding their use by stealth fighters and bombers. Furthermore, very-long-range hypersonic weapons would still need to fly tens of minutes to reach their targets, which can give an enemy time to detect and counter attacks. Finally, hypersonic weapons that cost multiple millions of dollars each will constrain the number the Air Force can afford to buy.

A better approach would be to field a new generation of mid-range, stand-in weapons capable of penetrating advanced IADS. Next-generation stand-in weapons with ranges between 50 nm to 250 nm will increase USAF’s lethality, reduce the number of sorties and weapons needed to kill targets in contested environments, and expand options for penetrating aircraft to launch high-capacity strikes in the face of high-risk defenses. Plus, with unit costs close to the SDB I and SDB II—less than $300,000 each—the Air Force could buy them at scale.

ATTACKING MOBILE OR HARDENED TARGETS

The increased mobility of China and Russia’s high-value weapon systems complicates the U.S. military’s ability to find, fix, track, target, and attack them at a distance. Deeply buried and otherwise hardened fixed targets are also challenging.

Although high-speed—even hypersonic—cruise missiles can help mitigate against a target’s movements, their higher cost will limit the number the Air Force and other services will be able to afford. In many cases, stealth aircraft will present a more effective option, given their ability to penetrate contested areas to deliver a larger number of more affordable mid-range, stand-in weapons per sortie. Penetrating aircraft like F-35As and B-21s also have on-board mission systems to independently find and attack mobile/relocatable targets, which simplifies their kill chains and increases the cost effectiveness of their strikes. Their ability to launch shorter-range stand-in attacks also reduces the time available for an enemy to take countermeasures.

Destroying hardened or deeply buried targets presents a different problem. As missile ranges are extended, their size and weight also increase because of fuel and other capabilities they need to fly longer distances. At the same time, the size of warheads they carry is reduced. Larger conventional warheads are needed to attack underground facilities, such as leadership bunkers or hardened shelters protecting weapons of mass destruction. Only bombers have both the capacity to carry very large “bunker buster” direct attack weapons such as the 5,000-pound GBU-28 and the 30,000-pound GBU-57 and deliver them over long ranges. It may be feasible to design mid-range PGMs, however, with enhanced warheads to take on some hardened targets.

TENS OF THOUSANDS OF TARGETS

The Air Force currently lacks enough PGMs to engage in an extended campaign against China or Russia while still meeting operational needs in other theaters, as required by the National Defense Strategy. This shortfall is an artifact of post-Cold War planning assumptions that sized DOD’s forces—including their munitions inventories—for short campaigns against lesser regional threats. Air campaigns against either China or Russia, however, could involve hundreds of sorties per day and last for many weeks. Absent sufficient PGMs, U.S. forces would not be able to sustain high-tempo strike operations regardless of how many combat aircraft it can bring to the fight.

The ability to quickly surge PGM production to meet theater commander requirements during a war with China or Russia could be decisive and should be part of the Air Force’s plans to prepare for peer conflict. This could entail creating new capacity in existing facilities to surge wartime production, or to maintain munitions production capability in “layaway” status so industry can surge production in time of need. An inadequate PGM stockpile combined with an inability to surge production could convince an aggressor that it could continue to fight and achieve victory after U.S. forces exhausted their strike capacity.

MAXIMIZE COST-EFFECTIVENESS

Leaving aside the operational limitations of long-range standoff weapons against mobile, relocatable, and other challenging targets, their cost is another barrier to buying them at scale. Costs increase with PGM ranges and sophistication, meaning that the longest-range, most complex weapons are typically purchased in very small quantities. The Navy only acquires a few hundred Tomahawk cruise missiles per year, and the total acquired over the life of long-range standoff weapons programs is well under 10,000 weapons.

A better, more cost-effective choice is to invest in next-generation mid-range PGMs that can be carried in significant numbers by penetrating stealth bombers and fighters. Other PGM programs suggest new weapons should cost $300,000 or less if they are to be affordable enough to acquire in the large quantities needed for high-intensity peer conflict. New mid-range PGMs suitable for stand-in strikes by penetrating fighters and bombers would help achieve this objective and create a PGM inventory that has the capacity Air Force airmen will need in the future.

Finally, the Air Force must be cautious about its dependence on non-stealth aircraft that must launch weapons from stand-off ranges. Because of the cost of those weapons, non-stealth aircraft like B-52 bombers and F-15EX fighters could quickly run out of JASSM-ER and other standoff weapons in a conflict with China or Russia. Procuring a future munitions mix that includes large numbers of more affordable mid-range stand-in munitions would help create a deeper magazine and convince adversaries that the Air Force is prepared to defeat any act of aggression that threatens the United States and its allies and friends.

CONCLUSION

The Air Force should adopt a strategy to transform its obsolescing PGM stockpile to a balanced mix that maximizes its capacity for a peer conflict, following these five steps:

1. Prioritize fielding “5th-generation weapons for 5th-generation aircraft” to take full advantage of the range, survivability, and capability of stealth aircraft to complete kill chains independently in contested environments.

2. Include a family of mid-range (50 nm to 250 nm) PGMs that can be delivered by penetrating aircraft on 100,000 or more discrete aimpoints.

3. Set an objective cost per weapon of $300,000 or less for these new mid-range, stand-in PGMs to maximize its “bang for the buck.”

4. Establish baseline low observability and other capabilities for these new weapons so they can penetrate advanced IADS and survive to reach their designated targets.

5. Ensure the new mid-range PGMs are capable against mobile, relocatable, hardened, or deeply buried targets.

As the Air Force creates a future PGM mix that is suitable for great power conflict, it must not forget it has an advantage that is unmatched by any other U.S. or allied military: a growing force of advanced 5th-generation fighters and stealth bombers. Developing mid-range, stand-in PGMs suitable for operations in contested environments would help the Air Force take maximum advantage of its stealth forces. This is a “must do”—the best, most advanced combat aircraft in the world will be ineffective if they lack a PGM inventory that has the capacity, survivability, and effectiveness needed for great power conflicts.

Col. Mark Gunzinger, USAF (Ret.) is the director of Future Concepts and Capability Assessments at The Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.