Advancing technology and the threat from China drive the Pentagon toward revolutionary change.

The Air Force’s acquisition system is getting a significant overhaul. The growing military threat posed by China, an aging U.S. workforce, and the opportunities and necessity presented by new digital technology are converging to accelerate the way the defense department develops and acquires its weapons.

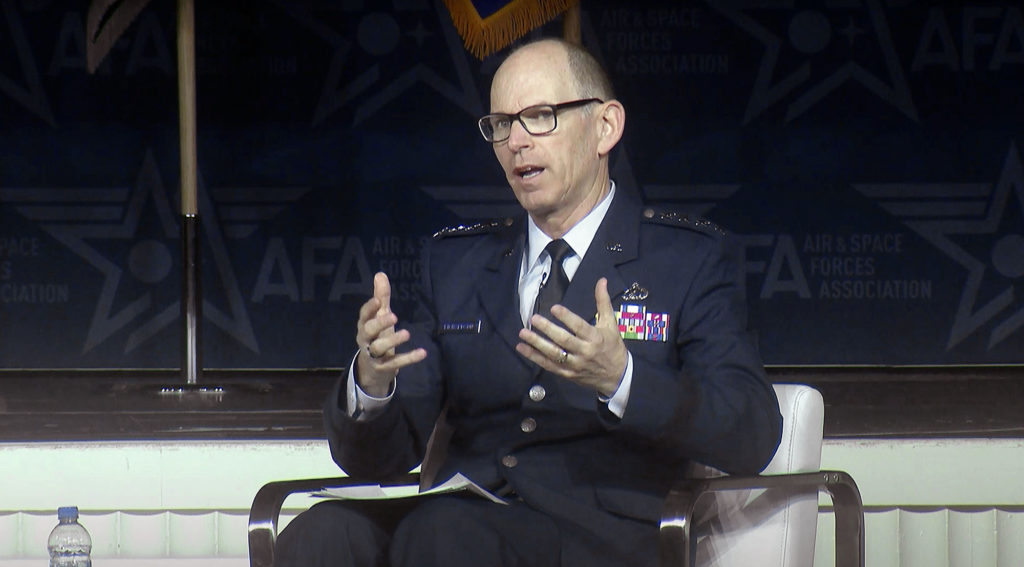

The use of digital engineering and modeling to design, develop, and sustain new systems is not a passing fad, but a change that is here to stay, said Gen. Duke Z. Richardson, head of Air Force Materiel Command. While most companies are immersing themselves in this new way of doing business, those that drag their feet will be left behind.

“Get on the bus, or you’re going to get run over by the bus,” he warned.

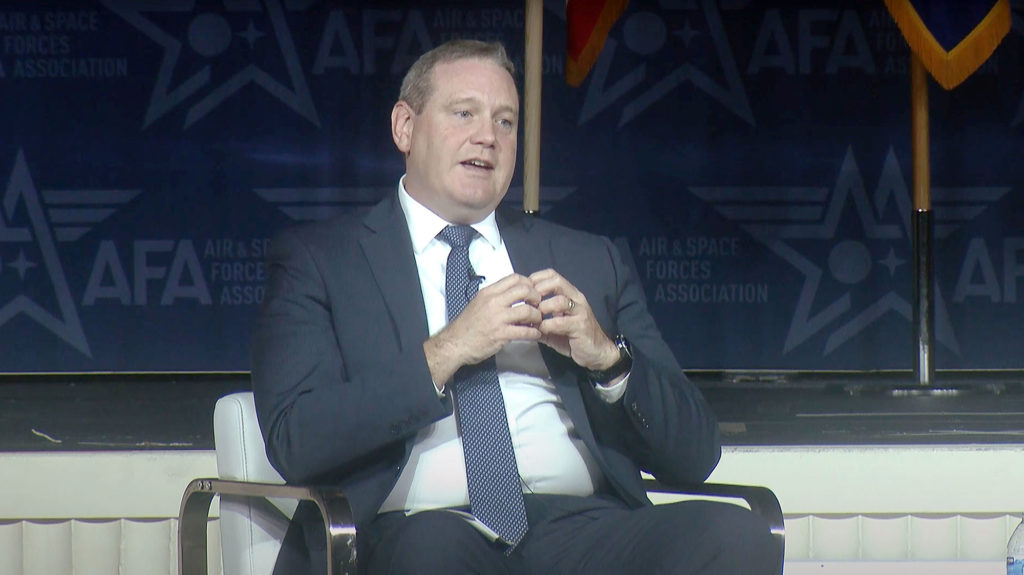

William A. LaPlante, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, said a few weeks later at an industry gathering: “All of you … should be moving—if you haven’t moved already—your engineering departments into the digital world.” LaPlante acknowledged that “digital engineering” has become a buzzword that doesn’t seem to mean the same thing to all audiences.

“You could say, it’s ‘automating the processes’” and about the “move to ‘paperless.’ But that’s not the magic of it,” LaPlante said. “What we’re talking about … is the ability to crunch designs overnight; tens of thousands of designs … digitally, so you can find design spaces you would never have found before.”

Digital engineering also accelerates the learning curve of new engineers, enabling newcomers “maybe one year out of school” to create “pretty sophisticated designs, whereas 20 years ago, it might have [required] someone with 10 years of experience,” to accomplish the same task.

LaPlante wants companies to apply digital engineering to every part of the design and production life cycle. “Are you truly doing it completely in digital?” he asked. “Are you truly doing it in design with less physical prototyping, and are you keeping a living digital twin? If you’re not doing that, then you’re not doing digital engineering.”

True champions of the approach tie in digitally with their suppliers, so that all partners have access to the same digital models, and that the impact of proposed changes is understood.

“If you don’t have access to it, you’re not doing digital engineering,” LaPlante said. Likewise, if the design and models reside locally, rather than in a shared, secure cloud computing environment, vendors are not yet where they need to be. “Make sure you’re really doing it.”

It’s not that digital engineering is a panacea that will solve all problems, LaPlante said. “But it is a way to move faster. It is a way to come up with designs that might have been counter-intuitive, and it’s also a way to accelerate the learning for engineers.”

THE AIR FORCE TAKE

Andrew Hunter, assistant secretary of the Air Force for acquisition, technology and logistics, said the Operational Imperatives laid out by his boss, Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall, demand faster, more efficient, and more effective acquisition than what has been possible in the past two decades. Speaking at AFA’s Air, Space & Cyber Conference in September, he said new war-winning capabilities are required in the mid-to-late 2020s, to ensure the Air Force can be successful “in a high intensity, peer-to-peer competition.”

That demands a “sense of urgency” and focus, he said. “It’s a very daunting task, because we have a lot of capability we have to deliver in a fairly short amount of time,” Hunter told reporters. But “we have to deliver to get the job done.”

China, Hunter said, now has the economic power and technological know-how to make good on its overt ambitions of becoming the world’s top military superpower by mid-century. That demands “transforming the acquisition system for the 21st century,” he said.

The Air Force’s job jar is overfull: modernizing its entire nuclear deterrence enterprise and fielding all-new technologies in the conventional force within the next decade, all while sustaining everything else.

Like LaPlante, Hunter said the Air Force will insist that engineers, operators, and industry work more closely together to provide fighting capability that’s relevant and can be updated swiftly. He wants the Air Force to refresh technology more like the commercial world, which updates at a near-constant pace. Better synchronization with the commercial world benefits the Air Force two ways: It will help USAF systems stay ahead of the threat, and also make the service a more attractive customer to companies that are not traditional defense suppliers. He calls this “shaping the innovation base.”

The new systems being developed are “incredibly software intensive,” Hunter said, so they do not “lend themselves to the kind of industrial models of acquisition that were the foundation” of USAF’s past breakthroughs.

Capabilities visible in real time mean “faster, more iterative” development, enabling “increments of capability in weeks and months rather than years.” These are objectives of USAF’s Digital Transformation initiative, he explained.

This methodology puts all the information for a new capability into a single database, allowing everyone involved—developers, engineers, managers, acquirers, users—to see progress in real time. The ramifications of changes can be understood more quickly, allowing for the consideration of an enormous number of alternatives in a relatively short time. On the Sentinel ICBM (the weapon formerly dubbed the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent), Air Force officials say they have been able to work through “millions” of trade-offs to achieve the optimum design.

“What I am seeing in our programs that have been implementing this is a much higher degree of maturity earlier in the design process,” Hunter said. Designers can make “informed choices” about trade-offs earlier.

Richardson sees the benefit not just in fielding weapons but sustaining them. If the digital foundations are built correctly, “it will actually allow us to accelerate all along the life cycle,” he said.

Another change heralded by digital engineering, Richardson predicted in August, is the end of “big bang” program milestones, such as critical design reviews (CDRs). The process becomes more fluid, less about stages and more about progress.

“This is completely transforming how we’re doing systems engineering,” Richardson said. Maintaining an up-to-the minute digital model and pushing decision-making to “the lowest level” means “cataclysmic, three-day” CDRs aren’t necessary. Richardson said such reviews make no sense, as he’s presented with a table full of drawings “like I’m supposed to notice if there’s [something] missing. C’mon. That’s no way to do business.”

He added that “we’ve got programs doing this now … as a normal part of the workday.” Programs may still have “something like” a CDR “where people like me … give it the stamp of approval,” the fact is the work has already happened. “Really, it’s been going on the entire time,” Richardson said.

Developers should have “traceability of test verification,” he said, meaning more testing will be virtual and less in the “real world,” saving time and cost.

But that doesn’t mean start-up costs will be less, Richardson said.

“It probably doesn’t require less people. In fact, it might even require more people at the beginning,” he said. Savings will come over time, not from the start.

Richardson said the Air Force will look for ways to get smarter about the entire sustainment enterprise.

“We’re going to dig in deep on this idea of digital materiel management,” he said. “We’re going to look at the digital tools to see if we can actually reinvent the processes.”

Richardson, whose job is to carry out Hunter’s policies, said he and Hunter agree that the users must be fundamentally involved in setting requirements and monitoring the products that the acquisition enterprise produces. Richardson said his job will be to make sure “the programs we deliver … are integrated with each other,” to facilitate their employment and so that they can function interactively, within systems like the Advanced Battle Management System.

The acquisition system is now thinking about platforms as part of “the entire fighting system, working together,” Richardson said at the spring conference.

“Closing kill chains” without the Space Force or even the other services will no longer work, he stated.

Program Executive Officers who “like to be left alone,” managing the risk in their program alone and “shielding themselves from connections to other things. … That’s going to have to stop,” Richardson said. “We’re not going to be able to do that anymore, not if we’re going to keep up.”

Richardson said he uses the term “‘revolutionizing acquisition”’ intentionally, “to be provocative; to kind of challenge ourselves.”

Hunter agreed. “I think we can really amplify the effect of our efforts when we’re working closely together” with industry and operators, Hunter said. Sustainment has to go hand-in-hand with new development, because “we can’t meaningfully deliver operational capability if it’s not sustainable, ready, and able to go into the fight. … There’s no capability if you can’t sustain it.”

The Air Force needs “resilient and secure supply chains” to accomplish its mission, he said.

THE WAY FORWARD

Richardson said programs should be constructed along lines suggested by former AFMC Commander retired Gen. Ellen M. Pawlikowski, whose prescription for success was threefold: Program managers God-like authorities, with limited oversight; sharp people; and money for risk.

That recipe has worked for the B-21 bomber, he said, and it’s why it’s one of the Air Force’s best-performing development programs.

Richardson said all this flows from what Kendall—a former Pentagon acquisition chief—wrote in his book, “Getting Defense Acquisition Right.”

Kendall outlines four objectives in the book, Richardson said: Setting reasonable requirements, putting professionals in charge; giving them the resources they need, and providing strong incentives for success.

With a large portion of the Air Force’s acquisition workforce nearing retirement, Richardson said the Air Force must offer the incentives necessary to “recruit, reward, and retain” skilled talent, just as much as it must “incentivize industry.”

A big part of the effort will be to rebuild the Air Force’s bench in systems engineering, which has atrophied, but which Kendall, Hunter, and Richardson all agree is critical to delivering the capabilities the Air Force needs.

Richardson also said AFMC will take a page from Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr.’s mandate to push decision-making down to the lowest-possible level.

“Not just empowering them, but equipping them so that they can be empowered,” Richardson said. That means providing the “tools and training” for the workforce to make the most out of digital methods. The workforce is “getting up to speed …on some of the tools,” but he’d like to see more embrace them. However, industry uses “a lot of different tools” and standards, and it may be too soon to mandate specifics, he said.

While the youngest workers are “super excited” about the new methods, “we’ve got to get the middle managers super excited,” he said.

Along with that, Richardson said he plans to “amplify the warfighter culture” in AFMC, so that every person in the command’s workforce understands their role and “feels very connected to the tip of the spear.” He has also previously said that surveys of AFMC personnel show they want to do “meaningful work,” which makes the connection between their jobs and the results in the field that much more important.

Hunter said one of the thorniest problems facing acquisition will be ABMS. In the past, the Air Force would typically hold a competition and choose a single company to manage or integrate such a program.

“There’s power in that, right?” Hunter said. “There’s a reason why our system has operated that way. It’s been so successful in the past.”

But ABMS “cuts across so many stovepipes” that a different approach is needed, he said. “It touches every single system that we operate, in every domain in which we operate,” he said. ABMS will require coordination among numerous program executive officers and “hundreds of program managers to be successful.”

Such complexity is not something the acquisition enterprise was built to handle, Hunter said, so “standards and interfaces” that are universally applicable are needed, as well as enforcement mechanisms. It will also be a challenge to budget for, because the requirements are under “no single entity below the level of the Secretary.”

Rather than a single contractor for ABMS, “you need a team approach,” Hunter said. All of the technical and organizational problems are so complex that they’re “bigger than one company can really address on its own … so we’re taking the team approach.”

Asked if the U.S. can match the speed with which China has advanced its new weapons programs, Hunter acknowledged that “the pace is fast.” China doesn’t have to deal with a two-party systems and congressional oversight. But “their requirements are not our requirements,” Hunter countered. China has “fundamentally different problem sets … to solve.”

The Air Force will focus on the problem sets it has before it, Hunter added, and Kendall’s Operational Imperatives “created the infrastructure to allow us to do that,” along with the urgency to do it quickly, and to accept risk “judiciously,” by “making good trade-offs.” Referencing the founder of Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works organization, Kelly Johnson, Hunter said that programs may need to limit themselves to one “miracle” apiece, rather than three.

Hunter added that most of the Operational Imperatives grew out of science and research programs already well underway with the Air Force Research Laboratory. The Air Force is also going to be very open to adopting systems in use by allies and partners, such as the E-7 Wedgetail developed for Australia, that will succeed the E-3 AWACS. This, too, will speed acquisition along.

When there is a viable solution “we could quickly acquire,” it, he said, the Air Force need not reinvent the wheel. Wedgetail, he said, can be seen even now as “already a success story.”