It’s time now to ramp up F-35A production beyond 48 jets per year.

The F-35 Lightning II, America’s most advanced production fighter jet, is on the cusp of a major leap in performance. Improved sensors, computers, and enhanced electronic attack systems will expand its weapons portfolio and ability to connect with other U.S. and allied systems across the battlespace.

The core upgrades are Technology Refresh 3 (TR-3), which advances the core computer processor, and Block 4, encompassing a range of capabilities that will be introduced over the next several years. Taken together, these capabilities mean the Air Force can now work to aggressively build the fifth-generation fighter force required by the National Defense Strategy. Beginning with the fiscal 2024 budget, every dollar for F-35 will fund TR-3-equipped Block 4 jets.

The need for those jets could hardly be greater. Long-delayed modernization plans mean today’s Air Force lacks the capacity to meet concurrent security threats posed by China, Russia, Iran and North Korea, even as threats continue to arise from non-state aggressors in the Middle East, Africa, and elsewhere. As the 2022 National Security Strategy states, “We stand now at the inflection point, where the choices we make and the priorities we pursue today will set us on a course that determines our competitive position long into the future.”

Airpower underpins much of that strategy. In peacetime, airpower deters adversaries and reassures allies; in war, airpower enables joint operations and holds both land and maritime targets at risk. Air Force fighters secure air superiority; deny an adversary’s use of the electromagnetic spectrum; and provide unparalleled intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance.

While the Navy and Marine Corps also have fighter aircraft, they lack the volume of aircraft with the full range of capabilities afforded by U.S. Air Force jets. Navy and Marine Corps combat aircraft also don’t provide a singular focus to joint objectives, as they are purpose-built to meet their service’s unique objectives.

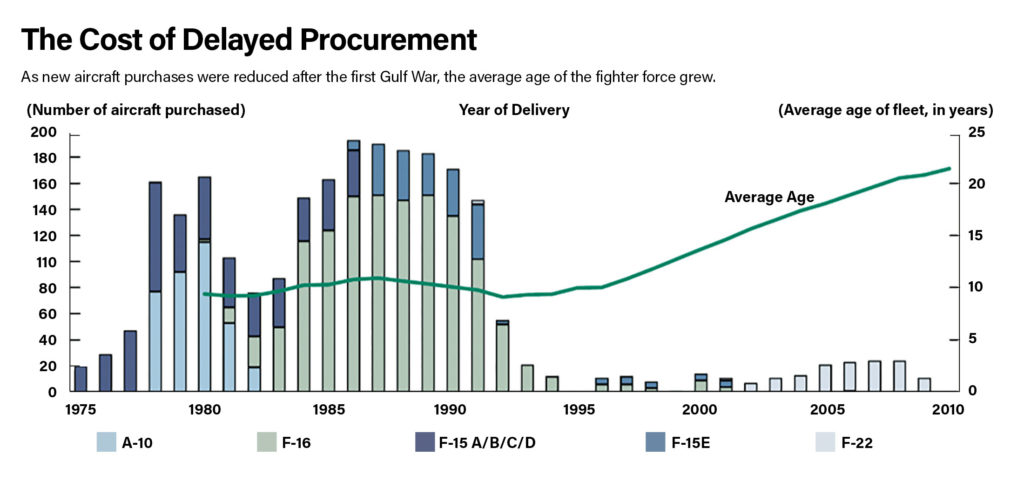

The Air Force’s fighter inventory today is geriatric and inadequate after years of neglect and delayed investment. Indeed, the Department of the Air Force has been the least funded compared to the Navy and Army for more than 30 consecutive years. With the bulk of its fighter fleet now consisting of A-10Cs, F-15C/Ds, and F-16C/Ds—all designed in the 1960s and ’70s—these jets now average 41, 38, and 32 years of age, respectively.

Even relatively new F-15Es average 30 years old. With each passing year, these aircraft are less available, as required downtime for repair eats into mission readiness. In 1990, the Air Force had 4,556 fighters; today, it has less than half as many, just 2,221.

Operational demand, however, never abated. As the number of fighters decreased, the workload actually increased through decades of no-fly zone enforcement and close air support operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Older fighters are now physically worn out and must be retired, but the Air Force has not been funded to procure a sufficient volume of replacements.

At a House Armed Services Committee hearing a year ago, Reps. Rob Wittman (R-Va.) and Donald Norcross (D-N.J.) highlighted the fact that the Air Force planned to retire over 600 fighters over the next five years, while acquiring just 246. As Wittman remarked, “400 is one heck of a big vulnerability, capacity, and capability gap.”

Of course, this shortfall was never the plan. The Air Force planned to field a high-low mix of F-22s and F-35s in the early 2000s, but the original F-22 requirement for 750 aircraft was ultimately reduced to 381, of which only 187 were built before production was cut short in 2009.

F-35 production, meanwhile, has yet to reach original estimates. By now, according to original plans, the Air Force should have had more than 800 F-35s, rather than today’s 272. The Air Force is now left trying to make the most of a fighter force out of balance with modern threats, especially those from China.

The Way Forward

The Air Force now needs to buy new fighters at an aggressive rate and to procure the right mix of capabilities to ensure the force will remain relevant over the long term. The Air Force’s 4+1 modernization plan is built around the F-35, F-15EX, F-16, and F-22, which is to be replaced by the Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) fighter in the 2030s.

The F-15EX can meet homeland defense requirements and carry large-volume payloads in forward-deployed regions. Without stealth, it cannot fly too far forward in highly contested environments.

The F-16 remains an efficient capacity filler for the homeland defense mission, and can take on forward roles where the threat is not too high, given that it also lacks stealth and other key survivability attributes.

The F-22 is a vital fifth-generation air superiority aircraft designed to fly and fight in extremely contested airspace. It should remain in the inventory until NGAD arrives in the next decade. NGAD promises to be extremely capable but also costly, perhaps “multiple hundreds of million dollars” per aircraft according to the Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall. That suggests an inventory of around 200 NGAD aircraft, which is low given high demand across a range of global commitments and growing threats.

The F-35, therefore, is the key to the Air Force’s fighter modernization strategy, offering a mix of advanced capabilities, including survivability against advanced threats and the ability to empower the information battlespace with improved sensors, processing power, and connectivity. It is competitively priced at around $80 million per unit, which allows the mass procurement needed to meet the Air Force’s capacity requirements.

As Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. has explained, the F-35 will be “the cornerstone of the fleet.” While the imperative for fifth-generation fighter aircraft technology was often debated over the past three decades, that is no longer the case. In many ways, it comes down to demonstrated results. As Gen. Mark D. Kelly, commander of Air Combat Command, explained:

“The voices of the fifth-generation pilots, or those who have flown with fifth gen and had it help clear a path to the target, or those who have flown against it and gotten shot in the face and were not sure where it was coming from—those voices started to spread out, and the believers of 5th gen are growing rapidly.

“These aircraft can penetrate defended airspace at lower risk, understand the battlespace thanks to the combination of sensors and processing power, team with other actors, secure mission tasks both kinetically and nonkinetically, and get home safe.”

However, Air Force officials contend that the service’s capacity solution is not as simple as procuring F-35s at a faster rate. The Air Force does not want to ramp up production aggressively until TR-3 and Block 4 capability is available. As is typical when pushing the edge of technology modernization, these upgrades have been slower to field than planned.

As with nearly every other successful combat aircraft, the F-35 was designed to be upgraded over time. TR-3 comprises a new integrated core processor (ICP) 25 times more powerful than its predecessor, along with an associated memory boost. These upgrades are required for the software enhancements and additional hardware improvements that come in Block 4.

TR-3 and Block 4 are actually a rolling set of 75 specific upgrades that will occur over several years. Their combined implementation will give combatant commanders, pilots, and maintainers greater lethality and survivability in highly contested environments.

The first TR-3-configured F-35 flew on Jan. 6, 2023, with several Block 4 technologies awaiting installation. This suggests funds authorized, appropriated, and obligated in the fiscal 2024 federal budget and beyond will pay for TR-3-equipped F-35s and at least the initial elements of the Block 4 enhancements, establishing the foundation for future upgrades.

The Air Force has never exceeded acquiring more than 60 F-35s per year—the service’s official request for fiscal ’23 was 33 aircraft, and the fiscal ’24 request was 48. Congress actually approved funding for 45 in fiscal ’23. While this growth is positive, it is too little to meet demand. Mitchell Institute analysis shows that to reduce the average age of the fighter inventory to 20 would require acquiring closer to twice that number of aircraft per year. The 2024 Air Force request seeks 72 fighters, 48 F-35s and 24 F-15EXs.

Recommendations

The Air Force must increase the rate at which it acquires fighter aircraft. Only the F-35 is in production and has the combination of stealth and information superiority needed. The F-16, F-15EX, and A-10 still have roles to play, but they lack the fifth-generation capabilities necessary to penetrate the threat space and create desired effects.

The Air Force therefore should:

Buy More Fighters. While the fiscal 2024 request to boost buys to 48 F-35s per year is a positive vector, the Air Force should accelerate procurement still more to build back the proper mix of modern capability and capacity. Given their fifth-generation attributes and affordability, F-35s should form the bulk of that annual buy.

Develop and Implement a Force-Sizing Construct. The mismatch between resources and demand is such that the Air Force needs to develop and implement a force-sizing construct that can clearly explain the scale of forces required to meet mission requirements stipulated by the National Defense Strategy. Resourcing that demand is a separate issue. Honestly acknowledging real requirements at strategic and operational levels makes it possible for decision makers to understand the risks entailed by allowing capacity gaps to exist. As the Ukraine conflict illustrates, once a war starts, it is very hard to surge production of sophisticated defense systems.

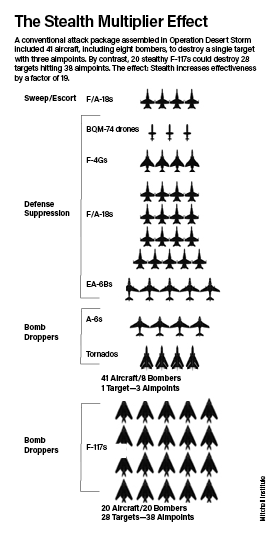

Harness Cost-Per-Effect Analysis. Cost is a predominant factor governing the scale and scope of the Air Force’s future fighter inventory. Yet the attributes that comprise modern combat aircraft are difficult to assess with unit-cost approach. Sensors, computing power, and connectivity are the attributes that will determine whether a combat aircraft succeeds or fails in combat, and likewise will shape the type of force packages employed. It may take dozens of lower-cost aircraft operating at higher risk to achieve the same effects as just a few F-35s, for example. Thus, the more expensive airplane—the F-35—may actually be the less costly solution, when viewed from a mission perspective. The best way to account for these realities is using cost-per-effect analysis to evaluate the true operational costs incurred to execute various missions. A cost-per-effect approach will properly shape the ratio of aircraft in the USAF fighter mix.

Ensure Program Stability. Predictable and consistent funding, stable requirements, and clear schedules are the foundational elements on which any healthy defense acquisition program is built. Considering that the F-35’s role in the Air Force’s fighter plan is vital for future combatant commander demands, it is imperative that DOD and Congress ensure these modernization efforts are executed in a stable, predictable fashion.

Ensure Testing and Evaluation Does Not Impede Necessary Results. The Air Force is moving a significant number of new aircraft as well as updated models through test and evaluation at a time when combatant commanders need these types on their flight lines fast. The current inadequacy of the Air Force fighter force is so dire that the Air Force may need to consider ways to streamline testing to ensure capacity gaps do not proliferate because of test and evaluation bottlenecks. Test and evaluation needs a major refresh to handle information-age systems more efficiently than the current enterprise allows. The Air Force should also consider how to add test and evaluation capacity, either by boosting the number of assigned aircraft or technicians or by better harnessing live, virtual, and constructive simulations.

Monitor and Steward Aerospace Industrial Base Health. Prime aerospace contractors are reliant on subcontractors with limited capacity. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, many of these firms were severely affected, exposing a lack of elasticity in the supplier base. If these strains are occurring in peacetime, wartime demand surges could prove impossible to answer unless the defense industrial sector can establish greater elasticity. Recent challenges to the weapons supply lines exposed by the Ukraine conflict are instructive here. Years of efficiency efforts shaved away the production elasticity in the armament industry, just as we are seeing now among aircraft makers. This problem must be solved proactively.

Divest to Invest is Not the Answer; Increased Investment is Necessary. Lacking cash, the Air Force is retiring systems to make budget space to pay for new systems, cannibalizing itself to acquire new capabilities. While this may have made sense after the Cold War when aircraft inventories were far larger, today’s smaller inventory cannot be cut further without undermining the viability of many mission areas. In fiscal 2022, the Air Force sought to divest 137 legacy fighters but only buy 60 new ones; Congress opposed most of the cuts. In fiscal 2023, the Air Force sought to retire 1,468 aircraft and only buy 467 across the FYDP—a net reduction of over 1,000 aircraft. Again, Congress declined to approve most of the retirements. The fiscal 2024 budget submission asks to retire 131 fighters, but only procure 72. This pattern can only result in a capacity death spiral. Increased Air Force funding is required to meet demand today, modernize for the future, and make up for decades of anemic aircraft buys.

Stewarding Human Capital is Part of the Fighter Equation. It takes highly trained pilots, maintainers, and other personnel to operate the fighter enterprise. The F-35 will only deliver optimal results if properly manned. The Air Force currently faces a shortfall of around 1,900 fighter pilots. Worse shortfalls exist within aircraft maintenance, especially as older aircraft stay in the inventory past planned service life, keeping existing personnel from transitioning to new aircraft. As with building new planes, shortfalls experienced during peacetime will only get more challenging in times of war, The Air Force, DOD, and Congress should assess talent retention, training capacity, force sizing, and manpower requirements to ensure crews are available and able to maintain proficiency.

Respect and Empower the Total Force. The retirement of F-15C/Ds from Kadena Air Base, Japan, beginning in the fall of 2022 is a warning signal, as are coming capacity shortfalls in the Air National Guard, which generally operates older aircraft. The Air Force is sized without an operational reserve today, because the Air Guard and Air Force Reserve is now factored into the force-sizing equation to meet even peacetime needs. In war, when capacity runs thin, the nation lacks the traditional operational reserve, a strategic risk to important missions like homeland defense. It is imperative that Air Force modernization is resourced to meet the demands of the Total Force, not just the active component.

Factor-in Allies. The U.S. Air Force does not stand alone in facing a fighter aircraft modernization crisis. Many allies are dealing with similar challenges. The rapid rise in international F-35 buys speaks to the scale of this challenge. DOD must ensure that F-35 production can meet the growing demand from international partners and allies in addition to U.S. requirements. If allies cannot procure aircraft from the United States, they will go elsewhere. That would reduce the warfighting interoperability, cooperation, partnership, and economy that come from sharing a common airframe. To help meet global demand, DOD and Congress should invest in expanding production capacity to boost F-35 manufacturing throughput above the current rate of 156 aircraft per year.

Conclusion

DOD, the Air Force, and Congress face a fighter aviation crisis that, left unchecked, could undermine every facet of joint force operations. Even cyber and spacepower will struggle to function if forward operating locations are under threat from the skies. The key to recovering the Air Force fighter force is in rapidly acquiring as many F-35As in as short a time as possible.

With TR-3 and Block 4 now close at hand, the Air Force can procure the most capable versions of the aircraft and boost capacity at the same time. Congress should ensure the funding is available and the Joint Program Office must hold contractors to schedule, performance, and budget targets. While this would require additive resources to achieve, the cost of the alternative is far higher: Failing to secure the skies, execute strike missions, and command the electromagnetic spectrum would prove disastrous for the United States and its allies.

The recent experience in Ukraine, in which neither side has achieved air superiority, is instructive. When Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky spoke to the international community in the wake of Russia’s 2022 invasion his plea was plain: “I have a need, a need to protect our sky. I need your help.” In a conflict with China, the U.S. will have nowhere to turn if it cannot control the skies itself. To do so, it must rebuild its Air Force fighter force.

As then-Secretary of the Air Force Heather Wilson warned in 2018, “The Air Force is too small for what the nation expects of us.” Since that time it has only grown smaller. ACC’s Kelly drives the resource argument home even more succinctly: “The only thing more expensive than a first-rate Air Force is a second-rate Air Force.”

Lt. Gen. Joseph Guastella, USAF (Ret.) is Senior Fellow for Airpower Studies at AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies. He was Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations (A3) in his last Active assignment. Lt. Col. Eric Gunzinger, USAF (Ret.), is a former Instructor Weapons Systems Operator with over 1,800 hours in the F-111, T-37, T-38, F-16, and F-18. He was Air Combat Command’s Program Manager for Testing and Certification of the F-35 pilot training simulator from 2009–2020. Douglas Birkey is Executive Director at Mitchell.