With the B-21 rollout, the Air Force begins recapitalizing the bomber force.

Seven years in development, the B-21 will make its first flight sometime in 2023. Northrop describes the new stealth jet as the “first sixth-generation combat aircraft,” and it will be the Air Force’s principal strategic strike asset for the bulk of the 21st century, according to Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin III, the featured speaker at the Palmdale, Calif., unveiling.

The curtain parted on the highly classified aircraft as Northrop begins outdoor engine runs, taxi tests, and works toward first flight. Other details—its expected performance, range, weapons capacity, and other capabilities, even the number of engines beneath its stealthy skin—remain withheld, to keep adversaries guessing.

The nighttime rollout at Palmdale was stage-managed to keep the bomber’s details hidden in plain sight. Everything from the lighting, the aircraft’s proximity to the invitation-only crowd, the types of cameras and lenses photographers were allowed to use, and the angle they were allowed to shoot from were designed to limit the insights experts could glean about the new airplane.

The Air Force plans to acquire at least 100 B-21s to replace its 45 B-1s and 20 B-2s over the next decade or so. Including the 75 re-engined and upgraded B-52s, the bomber fleet will then number at least 175 aircraft, although Air Force Global Strike Command leaders have voiced a requirement for as many as 250 bombers overall. The service has long held to the comment that the first B-21 will be available for combat use “in the mid-2020s.”

Standing before the sleek new B-21, Austin said its range will exceed that of any other bomber.

“It won’t need to be based in-theater. It won’t need logistical support to hold any target at risk,” he said. Its stealth is based on “50 years of advances in low-observable technology,” he added. “Even the most sophisticated air defense systems will struggle to detect the B-21.”

The Raider will be able to deliver conventional or nuclear weapons “with formidable precision” and support joint and coalition forces “across the full spectrum of operations,” Austin said.

Built with resilience in mind, Austin predicted the Raider will be “the most maintainable bomber” the Air Force has ever owned.

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. told reporters at a press conference the B-21 will be “a high-cycle aircraft, flying missions with “great frequency,” unlike the B-2, which requires hundreds of man-hours of maintenance to maintain its low observable features after each combat mission.

The airplane’s open-system architecture makes it “highly adaptable.” Northrop said the B-21 abandons the conventional “block upgrade” approach in favor of “continuous improvement.”

That approach is consistent with modern software development, which seeks to rapidly push out updates as they are ready. As a result, Austin said the B-21 will be able to employ weapons “that haven’t even been invented yet.” Its sensors and electronic capabilities will make it a “multi-functional” aircraft able to gather intelligence, conduct “battle management,” and integrate with allies and partners “seamlessly, across domains and theaters and across the joint force.”

Numerous U.S. allies sent representatives to the event, underscoring the importance of U.S. bomber capacity to coalition operations. Among them were Royal Australian Air Force Chief Air Marshal Robert Chipman, and U.K. Royal Air Force Air Chief Marshal Mike Wigston.

Austin thanked Congress for bipartisan support of the B–21, and lauded Northrop workers for “getting this big job done” without missing a beat during COVID lockdowns.

Although top Air Force leaders were present for the rollout, none spoke at the unveiling. Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall told Air & Space Forces Magazine later that, because of his business involvement with Northrop before taking on his present job, he recuses himself from actions related to the program. But Kendall also said Austin wanted to underscore that the B-21 is a joint, national program, and not simply a new Air Force asset. Bombers are both a long-range capability that can advance U.S. and allied aims conventionally, as well as part of the nation’s nuclear triad.

One senior defense official noted it may not have been a coincidence that the B-21 rolled out just a few days after the latest official Pentagon assessment of China’s military power, which detailed:

- A rapidly increasing Chinese arsenal of intercontinental ballistic missiles,

- A potential new stealth bomber for the People’s Liberation Army Air Force, and

- China’s lack of interest in joining existing strategic arms treaties.

The Raider is named in honor of the Doolittle Raiders of WWII fame, who delivered the first counterstrike of the war against Japan. The attack shocked Japan’s leaders, who believed they were geographically beyond threat. The Doolittle Raiders showed “the reach of American air power,” Austin said, saying the B-21 will do the same when it becomes operational.

The new bomber was developed in high secrecy by the Air Force’s Rapid Capabilities Office (RCO), in a streamlined acquisition program with limited oversight and direct reporting to USAF’s senior leadership. It has been held to a tight unit price estimated around $700 million—substantially less than the inflation-adjusted cost of the B-2—and has been described by congressional leaders on both sides of the aisle as a well-run program that is delivering the required capability under cost and on schedule. Digitally engineered from the start, Northrop has developed a “digital twin” to facilitate changes and upgrades.

Brown said the accuracy of the digital models should translate into fewer verification flights, requiring fewer live-fly test points.

Northrop Grumman CEO Kathy Warden said the B-21 design was optimized from among thousands of digital designs developed in a compressed period of time, which will permit “rapid technology insertions” as new capabilities emerge.

USAF acquisition executive Andrew Hunter said that while the B-21 contract called for an aircraft that could be “optionally manned”—meaning it can fly with or without an aircrew—“clearly, the focus”is on crewed operations—at least for now. The B-21’s stealth advantage over its competition was the key factor in its selection, he said.

Despite the airplane being presented in a way that revealed as little as possible about its capabilities, a few characteristics showed that the B-21 is not, as some wags have called it, the “B-2.1.” While it shares a general resemblance to the B-2, there are key differences.

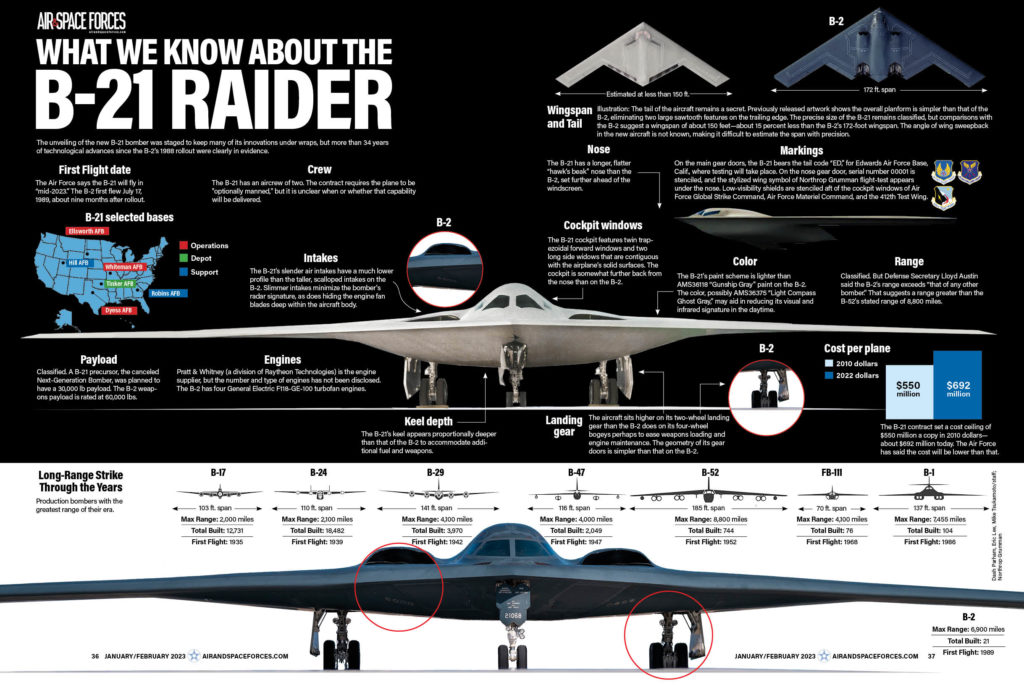

Its wingspan is smaller than that of the B-2, though not as much as has been suggested previously. The wing angle of sweep could not be determined, however.

- Its keel is significantly deeper and broader than that of the B-2, presumably leaving lots of room for additional weapons and fuel. The pronounced “beak” on the B-2 is longer and flatter on the B-21.

- Its keel is significantly deeper and broader than that of the B-2, presumably leaving lots of room for additional weapons and fuel. The pronounced “beak” on the B-2 is longer and flatter on the B-21.

- Its air intakes are far smaller than the scalloped clamshell intakes on the B-2, and almost organically blended into the B-21’s upper surfaces. This reduces the bomber’s radar cross section and hides the engine fan blades. An aerodynamicist told Air& Space Forces Magazine the B-2 likely makes use of the “Kutta effect,” by which airflow up and over the leading edge of the aircraft clings to the surface and enters the intake, instead of flowing over it.

- Its air intakes are far smaller than the scalloped clamshell intakes on the B-2, and almost organically blended into the B-21’s upper surfaces. This reduces the bomber’s radar cross section and hides the engine fan blades. An aerodynamicist told Air & Space Forces Magazine the B-2 likely makes use of the “Kutta effect,” by which airflow up and over the leading edge of the aircraft clings to the surface and enters the intake, instead of flowing over it.

- Although the B-2 is exactingly smooth, the B-21 surface is smoother still, its appearance evoking a finely sanded surface with no raised seams, not even around its canopy windows. Program officials said Northrop has dispensed with the tape and caulk used to smooth out the B-2’s surfaces in favor of new materials that are both stealthier and easier to maintain.

- The B-21’s trapezoidal forward windows and unusual side windows suggest they were shaped to exacting calculations necessary for a sharply diminished radar signature. The side windows may assist in aerial refueling operations, the Air Force has said, but may also be intended to help the pilots gauge distance from the ground on takeoff and landing.

- The bomber seems to sit higher on its landing gear than the B-2, likely making loading weapons and maintaining the engines easier. Its gear are also more centered under the fuselage than on the B-2.

- While the B-2 is painted an overall dark gray—specifically, AMS36118 “Gunship Gray,” which is good camouflage for nighttime operations—the B-21 is painted a light gray, possibly AMS36375 “Light Compass Ghost Gray,” indicating the Air Force plans to fly it more frequently in the daytime and at high altitude. Air Force shields were painted behind the cockpit, but in low-visibility paint, and it could not be discerned what organizations they represented. They likely include the RCO and Air Force Global Strike Command.

In the factory behind the B-21 on display, five more Raiders are in various stages of construction. These six aircraft will form the B-21 test force, according to Hunter, who also noted that after the flight-test program, they are expected to join the operational force.

At least two weapons for the B-21 are known. One is the B61-12 nuclear gravity bomb, and the other will be the AGM-181 Long-Range Standoff (LRSO) missile. The Air Force has disclosed little about LRSO; developed by Raytheon Technologies, it will initially be fitted to the B-52, but will later equip the B-21, providing it a stealthy, standoff capability as adversary technologies evolve.

Northrop’s description of the B-21 as a “sixth generation” combat aircraft has no official definition. Fifth-generation aircraft are acknowledged to be stealthy and equipped with advanced sensors and processors able to fuse incoming data to produce unprecedented situational awareness. “Sixth-generation” presumably ups the ante on the degree of stealth, as well as the capability of sensors, digital processing, and integration. Sixth-generation could also suggest other capabilities, such as the ability to operate without an aircrew and possibly use directed-energy weapons, such as lasers or high-power microwaves.

Since the program’s inception, the Air Force has said the B-21 will be the centerpiece of a long-range strike “family of systems,” which has come to be regarded as a series of off-board platforms or networks that collect battlespace information and enable the B-21 to fly its mission. What these are is not clear; they could range from satellite capabilities to bomber-launched decoys, jammers, and intelligence-gathering drones, which might fly ahead of the aircraft to fool or suppress enemy defenses.

The new bomber probably would have been named the B-3, but in 2016, then-Air Force Secretary Deborah Lee James named it the “B-21” to underscore its distinction as America’s first 21st century bomber, and “Raider” to honor the Doolittle Raiders.

The B-21 in many ways is the result of the premature end of the B-2 program. The Air Force planned to build 132 B-2s, but Congress halted funding at 20 (later 21) aircraft in 1997, in light of the receding Russian conventional threat and rising costs of the aircraft, due in part to Northrop being contracted to build a high-capacity factory to rapidly build the airplanes. When the program ended, there were only one-sixth as many aircraft against which to amortize those tooling costs.

Northrop continued to develop stealth technologies for the B-2, however, and the Air Force began working on a new program, called the Next-Generation Bomber (NGB), to leverage those investments. This new aircraft was also known as the “2018 bomber, because various studies and bomber roadmaps confirmed the need for a new bomber in that year, given the aging of the rest of the fleet and the advance of adversary air defenses. Defense Secretary Robert Gates canceled the NGB in 2008, however, saying it had grown too “exquisite” in its capabilities, and wouldn’t be affordable in the needed numbers. Gates directed the Air Force to start over; this time, setting unit cost as a key performance parameter. The 2018 in-service date was dropped.

The next program was dubbed the Long-Range Strike Bomber (LRS-B), with a baseline requirement that it cost less than $550 million per copy in 2010 dollars. In 2015, Northrop beat a Boeing-Lockheed Martin team for the LRS-B contract.

William LaPlante, then the Air Force acquisition executive and now undersecretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment, announced at the time that the new bomber would actually cost $515 million per copy in 2010 dollars so long as the Air Force built 100 aircraft.

To save money, Northrop tooled to build B-21s at a far less ambitious rate, said to be no more than about 15 bombers per year. LaPlante said this would insulate the program against potential sharp cuts in the annual buy. LaPlante said this plan would make the program “resilient” against budget swings.

Northrop also agreed to incentives that will reduce profits substantially if cost and schedule targets aren’t met. The development program is under a cost-plus-type contract, but the first production aircraft will be built on a fixed-price basis.

In 2010 dollars, the development program was set to cost $21.4 billion. In the Pentagon’s 2023 budget request, the Air Force said it will spend $19.536 billion on B-21 production through 2027. The funding profile calls for $108 million in fiscal 2022 (enacted by Congress), $1.8 billion in FY23; $3.5 billion in FY24; $4.4 billion in FY25; $4.6 billion in FY26, and $5 billion in FY27. A production ramp has not been disclosed.

Only the Air Force Chief of Staff can order a change in requirements on the B-21, and since contract award, no chief has done so. The “open architecture” approach obviates the need for requirements changes, since improvements can be added over time.

Northrop said the B-21 benefits from “more than three decades of strike and stealth technology” developed at Northrop. Besides the B-2, these include the YF-23 fighter prototype; the NGB, the AGM-137 Tri-Service Standoff Missile, the Tacit Blue stealth demonstrator, and numerous other presumed classified programs. The company said it’s using “new manufacturing techniques and materials to ensure the B-21 will defeat the anti-access, area-denial systems it will face.”

At the rollout, Northrop also showcased its current programs, displaying an F-35 fighter—for which it builds the center fuselage in partnership with Lockheed Martin—the E-2C Hawkeye airborne warning and control aircraft for the Navy; the Navy MQ-4C Triton, a derivative of the Air Force RQ-4 Global Hawk uncrewed ISR aircraft; the B-2; and the X-47, an uncrewed, stealthy-looking flying wing demonstrator which conducted autonomous operations off an aircraft carrier.

Northrop has also reportedly built a stealthy, high-altitude ISR aircraft to succeed the Global Hawk called the RQ-180, said to resemble the B-21.

Although the arrival of the B-21 indicates that the B-2 is on its way out, Northrop officials stressed that the B-2 has enough structural life to fly into the 2050s, and that it could be retrofitted with many of the technologies in the B-21, as manufacturing spools up and components become less expensive.

AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies has argued that premature retirement of the B-2s is an unnecessary risk. The Air Force should retain as much bomber capacity as possible, Mitchell argues, to counter China’s increasingly formidable threat.

“To build the force structure needed for the 21st century, the Air Force should consider retaining and modernizing its legacy force of B-1Bs and B-2s until it can procure B-21s in larger numbers and key mission capability and capacity parameters are met,” Mitchell said in a recent study.

Having the B-21 in production offers a “pathway … for the Air Force to grow its bomber force,” the think-tank said, by “retaining and modernizing the B-1B, B-2, and B-52, with B-21s procured additively.” Mitchell said the Air Force should shoot for an inventory of at least 270 bombers to meet the requirements spelled out in the National Defense Strategy.