In December 1991, Robert S. Strauss, US ambassador to the Soviet Union, visited KGB chief Vadim V. Bakatin in his Moscow office. Strauss—a genial Texan—thought he was making a simple courtesy call on a Kremlin official with whom he had good relations. Instead the American envoy got one of the biggest surprises of his life.

After the pleasantries were over Bakatin opened his safe and took out a thick file and a valise full of electronic devices. He handed them to Strauss.

“Mr. Ambassador, these are the plans that disclose how the bugging of your embassy took place, and these are the instruments that were used,” said Bakatin. “I want them turned over to your government, no strings attached.” Strauss was dumbstruck, according to an account of the incident he gave later that year.

| ||

|

The US Embassy building, under construction in Moscow in 1988. The tortured project took 27 years to complete. The building finally opened in 2000. ( AP photo by Boris Yurchenko) |

After years of denial, the Soviet intelligence arm was admitting its role in one of the most notorious espionage incidents of the 1980s: It had packed the new US Embassy office building in Moscow with sophisticated listening devices. The edifice’s structure was so riddled with bugs that some US counterespionage experts described it as nothing but a giant microphone. The unfinished building stood half-completed for years, as Washington struggled with how to deal with the intelligence debacle.

Bakatin expressed the hope that now the US could finish construction and move in. Strauss thought the sentiment genuine. But he knew mistrust remained on both sides.

“Mr. Bakatin, if I were to try to use that building, people would believe that you’d given me three-fourths of [the bugs] and kept [one]-fourth back,” said the US ambassador.

Today the US Embassy in Moscow is a lovely buff-colored structure in the city center, with large windows that reflect the Russian White House, seat of the Russian government, across the street. It’s the center of activity for a diplomatic relationship that in the 21st century remains one of the most important facets of American foreign policy.

But it was not always thus. In the latter years of the Cold War, the building was the “bug house” in news headlines. Embassy construction—using Soviet workers and materials—began in 1979, but was halted in 1985. US experts had determined the building was so compromised by KGB listening devices that it was unusable; at least, it was unusable if the US wanted its diplomats’ conversations to remain private.

US counterintelligence eventually discovered that Soviet workers had secreted a vast array of objects within the concrete used in the embassy structure, according to congressional reports and State Department histories of the period. Listening devices were just part of it. The workers had also thrown in unconnected diodes, as well as wrenches, pipes, and other junk, to frustrate electronic scanners and metal detection.

| ||

|

Vadim Bakatin (right), KGB head, takes a meeting in his office in 1990. In 1991, Bakatin turned over to the US ambassador a treasure trove of information about Soviet bugging operations at the US Embassy. (RIA Novosti photo) |

Some bugs were located at spots where metal I-beams were welded together. Lengths of steel rebar had been altered to serve as transmitters. Buried within one wall US inspectors found a sophisticated power source shaped like a bow tie, which they dubbed “batwing.” US engineers decided a nearby Soviet house of worship was suspicious—its lights would go on at odd times, and it seemed like a good spot from which to oversee the embassy’s bugs. Eventually they dubbed the edifice “The Church of Holy Telemetry.”

In a final twist, Soviet workers had arranged darker bricks in the building’s brick façade to spell out CCCP, the Cyrillic initials for USSR. It was as if they were thumbing their nose at Washington.

Appalled at the breach in security, many US lawmakers and intelligence officials urged that the building be torn down. They felt reconstruction—from the ground up—was the only method that would thwart the KGB. However, in the end, the embassy wasn’t razed.

“The American premium on sophisticated wizardry and pride in our overall technological superiority often leads us to ignore the possibility that others could be doing to us the same things of which we ourselves are capable, so we do not take elementary precautions against known or possible techniques,” said Rep. Henry J. Hyde (R-Ill.), then ranking member of the House Select Committee on Intelligence, in remarks about the embassy in 1990.

US officials should have been on alert from the beginning of the embassy’s construction. After all, Soviet agents had been eavesdropping on US diplomats, stealing secret US papers, blackmailing US guards, and generally harassing American diplomats in Moscow since the beginning of full diplomatic relations between the two countries in 1933.

| ||

|

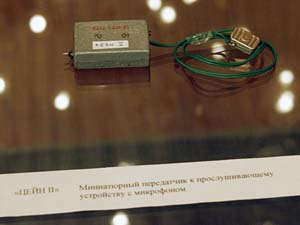

A miniature transmitter and microphone are displayed in Moscow during an exhibition of spy equipment. The US Embassy had been riddled with listening devices during construction. ( RIA Novosti photo) |

When the US opened its USSR outpost in that pre-World War II era, at first officials lacked such security basics as codes and safes. Communications with Washington occurred over open telegraph lines. The Soviet NKVD—forerunner of the KGB—quickly supplied “girlfriends” for the Marine guard contingent, according to a State Department history of the Bureau of Diplomatic Security.

One of the embassy’s early code clerks, Tyler Kent, had a Soviet mistress. A chauffeur for the US military attaché turned out to be another NKVD agent. “US Embassy officers knew of the Soviet espionage but did little to stop it,” read the diplomatic security history.

To some extent, US officials thought the espionage served American purposes. Ambassador Joseph E. Davies felt it would enable Soviet leaders to discover all the sooner that “we were friends, not enemies.”

But by today’s standards, the lax security is astonishing.

Sergei the Caretaker

In 1946, Soviet schoolchildren presented Ambassador W. Averell Harriman with a carved wooden replica of the Great Seal of the United States. It hung prominently in Spaso House, the US ambassador’s residence, for years—at least part of that time in the ambassador’s private study. Eventually, security personnel discovered a tiny microphone concealed within.

Sergei, the Spaso House caretaker, kept his basement apartment in the building locked at all times. Apparently no US official bothered to obtain a key from him until 1952. By then Sergei had decades to use the flat as a base from which to plant additional bugs.

In 1960, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., US ambassador to the UN, publicly unveiled the Great Seal bug before the Security Council to counter Soviet complaints about U-2 overflights. More than 100 similar bugs had been unearthed at US missions and residences in the USSR and Eastern Europe, Lodge charged.

By the 1970s, Soviet surveillance was simply a fact of life for US diplomats behind the Iron Curtain. In his memoir, Turmoil and Triumph, former Secretary of State George P. Shultz recalled that prior to his first trip to Moscow, in 1973, the Secret Service and CIA warned him repeatedly that bugs would be everywhere.

“The only place to have a private conversation was in a boxlike room in the middle of our embassy with electronic measures surrounding it. It was claustrophobic, but it was the one place in the whole city of Moscow, I was told, that was ‘secure,’ ” Shultz wrote.

| ||

|

||

|

In these stills from a film shot during a presentation to the UN Security Council, Ambassador Henry Lodge opens a copy of the Great Seal of the United States given to Averell Harriman by Soviet school children in 1946 and reveals listening devices the Soviets had hidden inside. The bugged seal hung at the US ambassador’s house in Moscow for years. |

By this point, it had long been apparent that the US needed a new Moscow embassy. American diplomats had occupied their chancery, an old apartment building, in 1953. It was cramped, inefficient, unsafe—and thoroughly vulnerable to Soviet espionage.

The USSR wanted to upgrade its facilities in Washington as well, so in 1969 the two nations reached a reciprocal agreement: The US would get a 10-acre site near its old building for a new embassy complex, and the Soviets would get a similar plot on Mount Alto in Washington, D.C.,where Wisconsin Avenue peaks on its rise out of Georgetown in the northwest quadrant of the city.

This pact set a 120-day deadline for further agreement on conditions of the new buildings’ construction. In a preview of what was to come, striking this particular part of the deal actually took more than three years, due to disagreements about edifice height and the degree of host country control over contractor work.

The US use of Soviet labor and materials was a “fatal error,” Hyde later charged on the House floor. But it was the era of détente, and President Nixon and Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger felt larger issues were at stake. In any case, Soviet workers would be cheaper, argued the State Department. Plus, the Soviets had built all other foreign embassies in Moscow. What could go wrong

Further haggling over details pushed back the laying of the cornerstone for the new embassy building to September 1979. It was clear from the start that counterintelligence would be a challenge, as the KGB maneuvered for ways to implant listening devices. At the time, US intelligence services thought they could neutralize any bugs they might find. This was overly optimistic, according to a 1987 report from the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence.

“Unlike the Soviets … the United States did not employ a systematic, stringent security program to detect and prevent Soviet technical penetration efforts,” judged the report.

For instance, Soviet officials overseeing the Mount Alto construction site in Washington routinely changed their blueprints without warning during the architectural bidding process, according to the Senate study. Their design plans were vague, with rooms identified as nothing more specific than “office space.”

In contrast US blueprints identified office spaces by name, making the location of sensitive areas clear to the Soviet workers—and their overseers.

The Soviets would use only concrete poured on site. The US accepted precast concrete forms constructed off site with no American supervision.

The Soviets inspected all materials carefully and were willing to halt construction work if they had questions. The US inspection system was less stringent, and the construction schedule ruled.

Soviet officials used about 30 of their own personnel to oversee about 100 US workers in Washington, on average. The US used 20 to 30 Navy Seabees to watch upward of 800 Soviet workers in Moscow.

| ||

|

Ambassador to Russia Robert Strauss (second from left) greets a USAF aircrew member in 1992. The year before, the Soviet KGB chief had turned over to Strauss details of how the USSR had bugged the US Embassy in Moscow. ( RIA Novosti photo) |

The Soviets used a badge identification system, maintained tight perimeter security, and installed multiple surveillance cameras. The US had perimeter sensors and closed circuit TV monitoring, but they were soon disabled due to various “mishaps,” according to the Senate intelligence committee.

In sum, US counterintelligence was playing catch-up almost from the beginning of the Moscow embassy project.

“By and large, US countermeasures against Soviet technical penetration had to be directed against a huge prefabricated structure already in place,” the Senate intelligence panel concluded.

By the early 1980s, some officials on President Reagan’s National Security Council had become concerned about the hostile foreign intelligence threat in general, and about the security of the new Moscow embassy in particular, according to a National Security Agency report declassified in 2011.

So in 1982, the NSA sent a team of specialized electronic intelligence personnel to the USSR to check on the situation. They found a chancery “honeycombed with insecurities,” according to the report, which is a partial history of NSA activity during the Cold War.

The NSA alerted the FBI, which conducted its own investigation and confirmed the seriousness of the situation. US intelligence and the FBI briefed Reagan on the matter.

“The State Department, already suspicious of NSA ‘meddling’ in embassy affairs, was reportedly unamused,” reads the NSA report.

Some diplomats felt the Security Council’s worries about embassy bugs were overblown. But in the end the evidence was too compelling.

On Aug. 17, 1985, the on-site US acting project director told the Soviet contractor to suspend all work on the new embassy office building. At the time it was 65 percent complete.

The rest of the US complex at the site, including residential and recreational buildings, was finished the following year, but the embassy itself remained undone, an expensive and very public white elephant. Many in Washington doubted that the US would ever be able to use the building for its intended purpose.

| ||

|

||

|

Top: The completed US Embassy in Moscow. Russia’s new embassy in Washington, D.C. Bottom: The Soviets employed a stringent security oversight system during the construction of their embassy. The US did not. |

In May 1990, legendary entertainer Bob Hope hosted a show for US Embassy personnel on a grassy field in the middle of the new embassy complex. He got some of his biggest laughs from 300 or so assembled American expatriates with jokes about the plight of the unfinished building at the site.

“What a shame that this new US Embassy has to be destroyed because of all the listening devices in it,” said Hope. “This place has so many bugs, it should be known as the roach motel.”

Then there was this one: “I’m not saying this place is bugged,” said Hope, “but I looked at myself in the bathroom mirror and said, ‘Boy, what a handsome guy!’ And the mirror said, ‘That’s funnier than any joke you’ll tell today.’ “

The audience played along. At one point, Brooke Shields stopped her act and told a director that she was hearing a strange sound. “Microwaves!” yelled some people in the crowd.As Hope’s comments show, at the time many in the US assumed the embassy was doomed. It was too riddled with bugs, and US counterintelligence would never be confident it had cleansed the place of them all. That was certainly the opinion of many in Congress. The Senate committee on intelligence, for instance, had recommended as early as 1987 that the building be torn down.

“The committee recognizes that demolishing an office building in which $23 million and the considerable energies of specialists in the field have been invested is a difficult and potentially controversial recommendation. However, failure to take action, even at this late date, would obligate further sizable expenditures in the future to no foreseeable gain,” said a panel report at the time.

This conclusion, however, was not universal. Former Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger spent five months examining the situation at the request of Shultz, and he recommended demolishing only the top three of the building’s eight stories. These would be replaced with new modular steel and perhaps a new annex to house the most sensitive embassy activities.

Top Hat

The 1972 construction agreement that allowed the Soviets to pour concrete off site, among other things, was the real problem.

“The prime party to blame is not the Soviets but ourselves. We have presented them with too much opportunity, too much temptation for them to resist,” said Schlesinger at a 1987 press conference.

In retaliation for the bugging, the US prevented the USSR from fully occupying its new Mount Alto complex. Both sides blamed the other for the situation. Stalemate became the status quo.

Conditions for US diplomats working in Moscow had long been problematic, due to lack of space and continuing security concerns. They only deteriorated over time. The bowling alley was turned into a communications center, for example. Half the parking garage was turned into workspace. Pressed for space, and facing increased congressional pressure for budget discipline, the State Department decided that Schlesinger’s partial demolition idea might work after all.

Bakatin’s attempt to provide the United States with a map of the listening devices in its bugged shell of an embassy did not quite work out as he had planned. He had given Strauss the plans following discussions with Prime Minister Mikhail Gorbachev and other leaders of the Soviet Union, but the US was suspicious of his intentions, and hardliners in his own government accused him of treason for the action.

A few weeks after his meeting with Strauss, the Soviet Union fell apart and the KGB itself was dissolved, its functions folded into other security agencies of the new Russian state. Then, at the end of 1991, the Soviet Union finally splintered, and the new Russian Federation rose in its place. In June 1992, Russia agreed to allow the US to finish the new embassy office building with a largely American workforce, using American materials, pursuant to an American design.

Two years later Congress granted final approval for use of $240 million of taxpayer funds for a Secure Chancery Facilities effort. Nicknamed “Top Hat,” this involved demolishing the eight-story building to the sixth floor concrete slab and construction of four new floors, plus a penthouse.

The bottom, unsecured floors would be used for public functions and other low-security activities. The higher, secured floors would be for more sensitive work.

Contractors hired for the job had to have top secret clearance. Lead firm Zachry, Parsons, and Sundt did not have a public telephone number and required workers to sign secrecy oaths. Construction materials, furniture, and other equipment for the building were shipped from Finland into Russia, escorted by armed US guards.

New construction began in September 1997. The embassy finally opened in May 2000, after more than two decades of delays and at a cost to the US of more than $370 million. Its tortured 31-year history remains a lesson in US diplomatic and technical hubris and a reminder of a spy-versus-spy world that may (or may not) be long past.

In celebrating the occasion, then-Ambassador James F. Collins called the new building “one of the most challenging construction projects ever undertaken by the Department of State. It has been a task … beset by the unexpected.”

That was putting it mildly.

Peter Grier, a Washington, D.C., editor for the Christian Science Monitor, is a longtime contributor to Air Force Magazine. His most recent articles, “CyberPatriot World” and “Aerospace, Robotics … and Hip Hop,” appeared in June.