In the 1950s, the Soviet Union loomed as a dangerous competing superpower, able to orbit satellites, brandish nuclear weapons, and possibly lead the world in development of intercontinental bombers and ballistic missiles. Despite furtive attempts to gain information through informants and spies, the United States had virtually no insight into Soviet capabilities or intentions, hidden as they were behind the Iron Curtain.

The perceived nuclear threat affected US security as never before. At the highest levels in the government, it was agreed desperate measures, even if internationally illegal, were necessary to gain information. Top US officials decided to use a small band of pilots flying the very advanced Lockheed U-2 aircraft as the point of the reconnaissance spear. At risk to their lives, pilots would break international law by flying over the Soviet Union. Their mission was to gather information deemed absolutely vital by no less a personage than President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The most famous of these pilots, Francis Gary Powers, became a hero of the first magnitude for his work before he was brought down over the Soviet Union on May 1, 1960, 50 years ago next month. However, Powers was never treated as a hero until after his death, when he was given belated recognition for his accomplishments.

|

The route Gary Powers took over the Soviet Union on the fateful 1960 flight. The red X marks the shootdown location, and the continuing dotted line is the intended flight path. |

An Offer USAF Couldn’t Refuse

The reconnaissance program Powers and his colleagues served was known by various names, but is usually referred to by its CIA cryptonym Aquatone. Its goal was to create an aircraft that could fly over the Soviet Union at altitudes beyond the reach of interceptors.

Soviet surface-to-air missile capability was not yet seen as a threat. The new aircraft was to be equipped with revolutionary cameras and sensors, so a maximum amount of information could be obtained during the surreptitious overflights of Soviet territory. The goal was for the aircraft to fly high enough to elude strong Soviet radars. The Air Force was already overflying the USSR in the SENSINT program, but Eisenhower wanted to minimize the use of military aircraft—for such flights could be construed as an act of war.

Only “civilian pilots” would fly in Aquatone. The plan was that, should one be shot down, Washington would describe the flight as a weather-reconnaissance or nuclear-dust-gathering sortie.

The government organizations involved in the birth of the program reached from the White House down to the Pentagon, CIA, and many other agencies. Eisenhower directed the CIA to manage the program and USAF to provide the infrastructure, training, logistics, and pilots.

The US previously obtained information on the Soviet Union with modified versions of standard aircraft, but none had the altitude capability to elude the latest series of Soviet fighters or the imminent threat of SAMs.

The U-2 came about through the audacity and genius of Clarence L. “Kelly” Johnson, who led the famous Lockheed Skunk Works. Johnson was aware that a special team of Air Force advocates had created a requirement for a long-range, high-altitude aircraft to overfly the Soviet Union. It did not disturb Johnson that Lockheed was not invited to the official 1954 USAF competition for this aircraft.

The manufacturers of cameras, lenses, films, sensors, and other vital equipment literally forced quantum leaps in technology to create the mission aircraft. Its designers deliberately sacrificed strength for weight savings to achieve the necessary altitude and range capability.

Johnson’s personality and reputation prevailed when he made an offer the Air Force could not refuse: Six aircraft and their flight test and support for $22 million. The first aircraft was promised for delivery within eight months, with an operational airplane to be ready within 15 months.

Johnson knew every pound of aircraft reduced range and altitude. He had the Skunk Works shave weight from the structure, making important compromises on both safety and comfort. These included using extremely thin aluminum skin panels, omitting an ejection seat, not pressurizing the cockpit, and creating a unique bicycle-style single main wheel and tail wheel. Droppable outrigger wheels were used for takeoff and wingtip skids for landing. The glider-like aircraft first flew in August 1955.

|

Powers pictured with a U-2, wearing the pressure suit required for its pilots. (AP photo) |

Free from the usual requirements of a development program, the Aquatone team complemented Lockheed’s design and production by creating a secret base in the Nevada desert for test and training. It was called “The Ranch” and was a direct predecessor of “Area 51” lore.

The Aquatone team also established the necessary agreements with sometimes reluctant foreign governments for overseas bases. Pilots were handpicked by a USAF team and subjected to a rigorous physical and psychological screening process similar to one used later by the astronaut program.

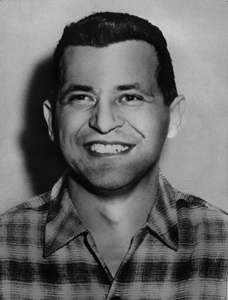

Francis Gary Powers was born Aug. 17, 1929. Known as Frank to his friends, he was an aviation cadet and was selected for fighter training before joining Strategic Air Command’s 468th Strategic Fighter Squadron at Turner AFB, Ga. There he did so well he was chosen to fly in gunnery competitions.

He began his work for the CIA in 1956, a member of a small group of highly qualified USAF pilots. They volunteered to undertake a mission about which they knew nothing except it was very dangerous.

Powers and his fellow volunteers made tough decisions to participate in Aquatone, resigning their Air Force commissions with the private assurance they could be reinstated with no loss of rank or seniority. They accepted long-term commitments to be away from home and that they could not tell family what they were doing or where they were going.

The irresistible lure for many of the U-2 pilots was the opportunity to fly a brand-new airplane that had spectacular performance but was laden with hazard. Powers and his colleagues soon learned they were to fly this untried and admittedly dangerous aircraft on long, nerve-wracking missions, some over hostile territory.

The first U-2 overflight over hostile territory took place on June 20, 1956 when Carl Overstreet flew from Wiesbaden, Germany, over Czechoslovakia and Poland. On July 4, the second overflight reached Leningrad. The Russian radar immediately tracked both aircraft, rendering useless the flimsy cover stories that the U-2s were conducting weather reconnaissance and atmospheric sampling. Every succeeding overflight was also detected by the Soviet Union, which issued private protests to the United States.

Unwilling to admit it could not prevent the intrusions over its country, the Soviet leadership fumed for the nearly four years following Overstreet’s mission. Soviet aircraft and missile designers were driven hard to come up with a means to counter the U-2. While no adequate fighter was developed, Petr Grushin at the Lavochkin design bureau led the creation of what became known as the SA-2 Guideline surface-to-air missile system. It was rapidly deployed, even though it had many operational problems and demanded expert attention for its effective use.

|

|

One Too Many

The CIA and Lockheed concluded early in the program it would be only one or two years before the Soviet Union produced interceptors and missiles able to shoot the U-2 down.

Powers performed well as both a pilot and navigator. While he originally thought he might undertake the new assignment for a year or two, he, like several of his colleagues, continued to volunteer, year after year, despite the demands, the primitive living conditions at forward bases, and the secrecy of their operations.

Powers was initially assigned to fly out of Incirlik AB, Turkey. He made his first official mission in September 1956, conducting electronic surveillance along the southern border of the Soviet Union. Powers flew many similar missions, careful not to accidentally penetrate the Soviet border. It was exacting work, for the pilot had to navigate by taking fixes using the radio compass.

In one of Powers’ early missions, he documented the presence of French and British warships preparing for their aborted invasion of Egypt in the fall of 1956.

In November 1956, Powers became the first U-2 pilot based in Turkey to conduct an overflight of the Soviet Union. The daring series of overflights brought back conclusive evidence the Soviet Union was shifting its emphasis from bombers to intercontinental ballistic missiles—information of the greatest importance to the United States.

For all of the U-2 pilots, each of the overflights was filled with tension. There was no way of knowing when the Soviets would acquire the weapon needed to shoot them down. As the fourth year of operation approached, concern rose that a U-2 might be lost at any time. Despite this, the CIA failed to prepare an adequate cover story for any captured pilot. The precautions it did take were haphazard and illusory. A small explosive device for destroying some of the vital equipment on board was installed, and pilots were offered the option of carrying a cyanide pill, or later, a curare-dipped needle.

Curiously, what should have been the most daunting aspect of the mission was also the most appealing—the inherent danger of flying a new aircraft on hazardous missions. The U-2 was continually improved, with an ejection seat being retrofitted in 1957.

The danger was real, since by 1958 no less than nine aircraft had been lost in accidents. The causes varied, but the U-2 was so fragile that in one case the jet wash from “buzzing” fighters was sufficient to break it up.

Powers continued to serve, although beset by familial concerns and his own certain knowledge that the law of averages would catch up. As safety officer for his U-2 detachment, he was very aware of the many U-2 accidents involving everything from electrical power failure to fuel lines.

The Soviets were detecting the U-2s early in their flight path, and an advanced Soviet missile—later known to be an SA-2—was fired at a U-2 over the Siberian coast in 1960. Nonetheless, the CIA obtained approval from President Eisenhower for one more overflight.

It proved to be one too many.

Powers was selected for the flight in the U-2 designated Article 360, which had previously run out of fuel on a mission and been damaged in a belly landing. After a delay waiting for final authorization, he took off early in the morning from Peshawar, Pakistan. His route was to take him across Afghanistan to enter the Soviet Union, then north by northeast to Chelyabinsk and Sverdlovsk, west to Kirov, northwest to Murmansk, around the Scandinavian peninsula, and finally landing in Norway.

Flying at about 70,000 feet, 1,300 miles into the Soviet Union, the U-2’s autopilot failed, and Powers made a decision to continue the flight using manual controls—a very demanding task.

With every one of these U-2 missions, the Soviet air defenses were also finding things extremely taxing. From Premier Nikita Khrushchev down, the entire Soviet Union wanted the intruder caught. All air traffic in the Soviet Union was shut down—the U-2’s destruction was demanded.

About four hours into the flight, the Soviet efforts paid off when a single SA-2 detonated near enough to the U-2 to blow its tail off. Powers was aware of a huge orange light followed by a violent tumbling as his aircraft soon shook itself apart.

|

Gary Powers (r) sits in the dock of the court in Moscow at the start of his August 1960 trial for espionage against the Soviet Union. |

Thrown about the cockpit, Powers was unable to get himself in position to eject. The aircraft had lost half of his altitude when he was finally able to push himself clear of the cockpit to bail out.

Powers was captured as soon as he landed. He was immediately rushed to Moscow.

When Powers became unquestionably overdue, consternation broke out in the United States. CIA Director Allen W. Dulles and Deputy Director of Plans Richard M. Bissell Jr. had assured Eisenhower that no U-2 pilot could survive a shootdown at the design altitude of 70,000 feet.

Cold War politics accelerated after his capture. Khrushchev dumbfounded Washington on May 7 by announcing he had evidence from the airplane and a live pilot.

Khrushchev then embarrassed Eisenhower at a May 1960 summit meeting in Paris. He presented an ultimatum concerning Powers’ flight, stating the Soviets would leave the summit unless Eisenhower condemned the flight as provocative, guaranteed there would be no future flights, and punished the individuals responsible for the operation. Eisenhower agreed only that there would be no future flights, and the summit broke up with Khrushchev convinced he had won a major propaganda coup.

Powers withstood intensive Soviet interrogations in the infamous Lubyanka prison. His trial was a sham, with Roman A. Rudenko, notorious for his role in the purging of Stalin’s enemies, as prosecutor.

Inevitably found guilty, Powers was spared the death penalty as a gesture of Soviet “humaneness” but sentenced to a three-year term in the cruel Russian prison system, followed by seven years at hard labor. He then had an 18-month sojourn in filthy Russian prisons in Moscow and Vladimir, enduring a primitive diet and living conditions.

Powers gave away only information he knew to be available already to the Soviets. Ironically, on Aug. 19, 1960, the day the Soviets convicted Powers and sentenced him to prison, the first Corona film capsule was recovered near Hawaii, thus permitting satellite reconnaissance overflight of the USSR to continue from outer space.

|

Powers, just hours after his return to the United States in February 1962. |

A Sour Homecoming

After much negotiation, Powers was returned to his country in February 1962 in a spy exchange for Col. Rudolph Abel.

By all rights, Powers deserved to be decorated at the White House—he had earned the honors. His many previous overflights had gathered incredibly important information, and he had shown his steadfast heroism in withstanding the torments of the Soviet system. Instead, he was badly treated by the government for which he had risked life and freedom.

Powers resented that, upon his return, he was smeared by a rash of ill-founded commentary. Writers and commentators complained righteously that Powers had not blown up his aircraft, not committed suicide, and even that he had managed to survive the Soviet imprisonment.

Far worse were the official positions taken by the very men who had backed the program, especially the CIA. The pilot had obeyed his orders exactly and defended himself and his country ably while on trial.

The CIA failed to support him publicly or provide an adequate cover story for an event they knew was inevitable—a downed U-2.

Despite his treatment, Powers remained convinced he had done the right thing. Championed by Kelly Johnson, he worked as a test pilot at Lockheed for seven years, and then became a helicopter pilot broadcasting traffic updates in Los Angeles.

Powers died on Aug. 1, 1977 when his helicopter crashed after it ran out of fuel. He was 47.

On the 40th anniversary of his U-2 flight, a ceremony was held at Beale AFB, Calif.—still the home for U-2 operations. Powers’ record was praised and his family received several posthumous awards: The Air Force awarded him the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Prisoner of War Medal, and the National Defense Service Medal, while the CIA, then headed by Director George J. Tenet, awarded him the Director’s Medal.

The commander of the 9th Reconnaissance Wing, then-Brig. Gen. Kevin P. Chilton, said, “The mind still boggles at what we asked this gentleman and his teammates to do back in the late 1950s—to literally fly over downtown Moscow, alone, unarmed, and unafraid.”