Stealth aircraft have been around a surprisingly long time—35 years. The F-117 had its beginning in a 1974 design contest. By the time the last one retired last year, three more stealth aircraft types—the B-2, F-22, and F-35—had been built or were in the works.

Stealth had moved from the pages of obscure physics journals to pre-eminence in USAF’s arsenal.

Proof of the high value of “low observable” airplanes also has been around a long time now. It emerged in the 1991 Gulf War, when a handful of F-117s accounted for 40 percent of all attacks on strategic targets. The Air Force ever since has believed stealth should define its combat air forces.

|

A B-2 Spirit from Whiteman AFB, Mo., soars over the Pacific Ocean. |

For all that, the nation’s track record on buying low observable aircraft has been dismal. The Pentagon acquired fewer than 60 F-117s. The Air Force was allowed to procure only 21 B-2 bombers—not 132, as originally planned. USAF has been cleared to acquire 183 F-22s; that is 198 short of what the service considers a minimum requirement.

True, Pentagon plans call for buying as many as 4,000 stealthy F-35s for the Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps, as well as select allies. None are yet operational, however, and that proposed number seems bound to shrink.

On the other hand, at least the Air Force has some LO aircraft. Nearly four decades into the stealth era, the Navy and the Marine Corps have none. The Army is even further behind.

Why, after 35 years of development, does the US have fewer than 150 stealth aircraft on its ramps? The reason does not stem from technology. It stems from politics.

Stealth thrived when it had friends in high places. In the 1970s and 1980s, backing for the secret technology crossed party lines and remained strong and durable through the Nixon, Ford, Carter, and Reagan Administrations. The reason was the demand of national security. Soviet fighters and surface-to-air missiles had evolved to a point at which some feared the B-52 might not be able to reach its targets in the Soviet Union. Credible deterrence was at stake.

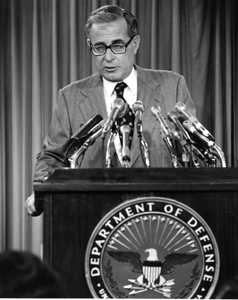

Harold Brown, Jimmy Carter’s Secretary of Defense, and William J. Perry, his undersecretary of defense for research and engineering, saw the problem without any difficulty. “By the mid-1970s,” Perry recalled in a speech, “NATO and the United States were looking at a Soviet Union with parity in nuclear weapons and about a threefold advantage in conventional weapons.”

Perry noted, “Many in the United States began to fear then that this development threatened deterrence.”

|

Secretary of Defense Harold Brown speaks at a press conference in 1980. The Nixon, Ford, Carter, and Reagan Administrations all supported stealth. |

Stealth and a series of nascent information technologies were at the center of Brown’s so-called “offset strategy.” The information technologies would go on to blossom as enhanced situation awareness, better intelligence-surveillance-reconnaissance, and full-fledged precision attack. However, US forces still had to have a way to get an aircraft close enough to the targets, and that’s where stealth came in.

When Perry learned of DOD’s secret low observable aircraft work, he concluded that, if stealth worked, it would give the Air Force an “overwhelming advantage.” He told the director of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency that he “would have all the resources needed to prove out the concept as quickly as possible,” Perry later recounted in a talk.

Air Superiority—and Stealth

On Perry’s watch, the F-117 program leaped from development to fielding after Lockheed’s design beat a Northrop contender.

Then, in 1980, USAF began its competition for the Advanced Technology Bomber. Northrop beat Lockheed this time, and went on contract for what became the B-2 bomber.

President Reagan took office on Jan. 20, 1981. The former California governor had campaigned on a platform of renewing American military power. He wanted superiority—and among other things, that meant stealth.

Reagan’s Secretary of Defense, Caspar W. Weinberger, became a staunch supporter of stealth for the same reasons that made believers of Brown and Perry.

Soon after he was sworn in, reporters asked what surprised Weinberger most about the Pentagon. “The principal shock was to find out, through daily briefings, the extent and the size of the Soviet buildup and the rapidity with which it had taken place—in all areas, land, sea, and air,” Weinberger replied.

Weinberger, during his years as a tight-fisted, budget-cutting senior official in the Nixon Administration, had earned the nickname “Cap the Knife.” When it came to stealth, though, Weinberger was no penny-pincher. He met with Air Force officials running the B-2 program every quarter. Even as the bomber struggled through requirements changes and unprecedented development challenges, Weinberger made sure dollars were never holding the program back.

The Weinberger Pentagon was so sure about stealth that it even backed a high-risk Air Force program to develop a supersonic stealth fighter—then known as the Advanced Tactical Fighter.

The early stealth programs were immensely complicated, but strong leadership and a clear calculation of national interest allowed the programs to press on through their difficult times. This continued to be the case, for the most part, in the George H. W. Bush Administration of 1989-93.

When Bill Clinton won election, Perry returned to the Pentagon as the No. 2 official. He rose to become Secretary of Defense, 1994 to 1997. His policy of preventive defense embraced the regional politics of the post-Cold War and pushed Pentagon streamlining. It also underscored the importance of dominant military power, even with smaller forces.

The F-22 was completing system development in preparation for the production first flight in late 1997. While Perry was in place, the stealth fighter was safe.

The Air Force opted to cease purchases of non-stealthy fighters in anticipation of an F-22 force that could replace F-15s—and some F-16s—at a rate of one-to-two. The desired end state was a smaller but more capable force.

Research for what became the F-35 began under Perry’s supervision, too.

Not long after he left, however, support for the F-22 faltered. The 1997 Quadrennial Defense Review cut the program deeply, and against Air Force wishes, for the first time.

Still, the 1997 QDR left open a chance for the Air Force to request more F-22s at a later date.

William S. Cohen, the next Defense Secretary, was no foe of stealth either. He scolded Congress in 1999 for threatening cancellation of the F-22 program.

“Canceling the F-22 means we cannot guarantee air superiority in future conflicts,” Cohen wrote in a letter to Rep. Bill Young (R-Fla.) in July 1999. Cancellation, he went on, would “have a significant impact on the viability of the Joint Strike Fighter program.”

Perry explained: “The F-22 will enable the [F-35] to carry out its primary strike mission. The Joint Strike Fighter was not designed for the air superiority mission, and redesigning it to do so will dramatically increase the cost. An upgraded F-15 will not provide this dominance and will cost essentially the same as the F-22 program.”

However, the relatively bloodless regional wars of the 1990s had cooled American fervor for advanced technology, and, equally dangerously, made fighter and bomber modernization appear a relatively low priority.

|

Have Blue, a low-signature, experimental, subsonic airplane powered by two J85-GE-4A engines, led to the development of the F-117. |

The Essential Point of Stealth

To close observers, the 1999 Kosovo air war should have reconfirmed the valuable role of stealth against unexpected regional adversaries. It didn’t, despite the stellar combat debut of the B-2 bomber and the surprise loss of an F-117.

The B-2 was the first aircraft to employ the GPS-guided Joint Direct Attack Munition in combat. It was the only platform capable of conducting precision attacks in all weather.

Serbian airspace was not a friendly place. The old Soviet Union was gone, but its “threats” were not. Ten years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, airmen were still scrambling to defeat Soviet exports. Serbian air defenses gave NATO aircrews a taste of the risks.

What was different about this air war was that NATO airmen faced a significant number of older SA-3s and SA-6s in the former Yugoslavia’s arsenal. The missiles continued their attacks, sporadically, during most of the campaign. The integrated, upfront blow—a la Desert Storm in 1991—was not possible in the former Yugoslavia. For example, politics dictated that a pesky pair of early warning radars in Montenegro was off-limits. They functioned throughout the 78-day air campaign.

Stealth was designed in part to break free from the increasingly complex battle of electronic countermeasures. As RAND analyst Benjamin S. Lambeth wrote of the conflict: “The F-117 and B-2, with their first- and second-generation stealth features, now allow [commanders] to conduct vital operations in the most heavily defended enemy airspace [where] no number of less-capable aircraft can perform at acceptable risk.”

That was the essential point of stealth.

In fact, the B-2 was the only asset sent into combat without accompanying radar-suppression aircraft. On one particular occasion, two B-2 pilots earned Distinguished Flying Crosses for completing a bombing mission on a night when all other attack aircraft, including suppression of enemy air defenses assets, were grounded due to bad weather.

Not that stealth aircraft got a free pass against air defenses: One F-117 was shot down, probably by an SA-3, but its first generation stealth technologies were far from state-of-the-art by 1999.

Stealth was well-suited to retaining technological superiority even in an era of diverse, regional threats. After development of the F-117, USAF specifically aimed to make its stealth platforms capable of a wide range of missions. The goal was to position stealth bombers and fighters as the centerpiece of USAF’s 21st century force structure.

Take the transition from the F-117 to the B-2. The F-117 was a breakthrough, but its original mission was deliberately limited in scope.

The Nighthawk’s mission “was to carry two laser guided bombs to strike missile sites in Eastern Europe and leave. That was it,” said retired Lt. Gen. Richard M. Scofield, who was program director for the F-117 and later for the B-2. The F-117 lifted avionics and subsystems from other aircraft and wrestled in its early years with difficult maintenance challenges.

In contrast, the B-2 was designed for a full set of nuclear and conventional missions from the outset, and built sturdy to take its place in the force structure for decades.

A few years later, the F-22 requirement was set. As far back as 1983, USAF pinned substantial technological hopes on the F-22 as the major front-line replacement fighter.

The plan was for stealth aircraft to incorporate advanced radar, onboard imaging, defensive systems, and all the best avionics the American aerospace industry could offer.

|

F-117s hold for takeoff at Holloman AFB, N.M. The Nighthawk’s retirement has left the nation with just 150 operational stealth aircraft. |

“We are now looking at an aircraft with tremendous advances over existing systems, including fully integrated defensive and offensive avionics, greatly reduced observables, efficient supersonic cruise, a significant increase in fuel efficiency, greater range, … and high maneuverability provided by integration of systems, new aerodynamic design, and vectored thrust,” said Gen. Robert T. Marsh, commander of Air Force Systems Command.

However, somewhere along the line, the stealth aircraft began to be seen as expensive luxuries, rather than mainstream force structure necessities.

Cost was no doubt a factor. The price for maturing technology and conquering the unknown was hefty. Cost influenced curtailment of F-117 procurement, and became lethal for the B-2.

Yet the choice was not attractive.

Quality or Quantity

Had USAF not chosen stealth in the 1970s, the alternative was to go cheap. In an era when the Soviet Union could field 7,000 aircraft, buying cheaper fighters in large quantities—to account for high attrition—was seen by many as a valid approach.

The Air Force chose quality over quantity. Analysis and experience suggested quality alone would allow USAF to get its job done, but the hankering for a low-cost fighter lives on even today.

Aiming for quality has caused USAF to pay a penalty, it seems, for aspiring to acquire topline capabilities, even in a smaller force.

Contrast the decade-long beating the Air Force has taken over its F-22 plans with the case of the Navy.

Stealth aircraft have been flying for more than 30 years but the Navy has never operated them—not entirely by choice. The A-12 stealth attack jet aircraft, which went belly up in 1991, compelled the Navy to move quickly to procure the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet or face a dearth of carrier-capable aircraft. The Navy could not afford to wait.

Left with no other option, the Navy successfully fielded the Super Hornet, which has proved to be a capable near-term fleet solution.

Yet few—even in the Navy—would argue that the Super Hornet is a good “Day 1” choice to send into heavily defended airspace. The Navy’s derivative approach may have proved successful precisely because it was modest.

The stealth and other advantages in the F-22 were the path to a smaller, much more capable, and ultimately a more affordable force.

Recent Pentagon overseers have been content with a simpler aircraft, however. So, in part, what happened to stealth was that the Pentagon lost its desire to pursue the best in airpower.

Viewing stealth aircraft as luxuries sets a dangerous course.

|

An F-22 from the 27th Fighter Squadron, 1st Fighter Wing, Langley AFB, Va., performs maneuvers using full afterburner. |

What was never adequately explained to the public was that the F-22 was not intended to replace legacy fighters on a one-for-one basis. The F-22 program was to replace more than 700 legacy fighters. The Air Force in the 1990s set a requirement for 442 Raptors to meet that need (since revised to 381), but the Pentagon has mandated repeated cuts. The program of record called for only 183 F-22s at the end of 2008.

Only the F-35 has stayed out of the comptroller’s doghouse. On the surface, the F-35 appears to be a bargain because its cost can be amortized over nearly 4,000 aircraft for US and international customers.

The final factor holding back stealth is relatively novel. It is the idea that stealth is about to be countered and that, as a result, investment in the F-22, F-35, or a next generation bomber will be moot.

The Soviet Union talked about countering stealth as soon as the B-2 came out of the black world. “For every action, there is a reaction,” Marshal Sergey F. Akhromeyev said at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., in July 1989, days after the first flight of the B-2. Akhromeyev, who was the Soviet Union’s top military advisor to President Mikhail Gorbachev at the time, left no doubt that his country would be taking measures to counter stealth.

Stealth engineers have known all along that their work was about a series of trade-offs that could greatly increase tactical advantages for US airmen. Engineers testing cruise missiles in the 1960s observed that low-frequency radar could pick up smooth, stealthy shapes. The idea for the B-2, for example, was that it might be detected fleetingly, but ground controlled interceptors would not be able to establish a track of sufficient quality to engage the bomber.

A Subtle Business

Discussion of countering stealth centers on two topics. The first is how to unmask the radar signature reduction attained through stealth. The second is whether the radio portion of the spectrum—often referred to as the RF spectrum—is still where the fight is. Some contend that infrared will become the next detection arena.

Unmasking radar is a subtle business. If stealth is a handful of methods for altering the expected return to the radar, then counterstealth has to overcome those measures.

There has been great exaggeration about countering stealth. It is based in part on a lingering misconception that stealth aircraft are not detectable. The aircraft were never intended to be invisible, nor was it claimed they would be. What the F-117, B-2, and F-22 designers aimed to do was to overturn the existing tactics for air defense. They did so in several ways:

-

Herding radar returns into controlled patterns so that, instead of radiating 360 degrees, the attacking aircraft had minimal spurts of radar return in known areas—which would be pointed away from threat radars, or too fleeting for steady detection and tracking.

Developing onboard systems for locating threats and showing the aircraft’s “best face” to them.

-

For the B-2, optimization to fly at high and low altitude.

Thus the counters to stealth have always been part of the advanced design concepts. Every low observable feature—from design and coating to seal and antenna—is evaluated for its strengths and weaknesses. Continued maintenance and testing of fielded low observable aircraft is like a daily reminder of the integrated balance required for stealth.

Among the stealth trade-offs, infrared signature is one of the classics. Reducing infrared emissions is difficult, but has long been a design requirement for low observable aircraft. Advances in adversary infrared search and track capabilities are certainly something to keep an eye on.

Against surface-to-air missiles, the challenge is not much changed: delay or obfuscate tracking. Here the continued advantages of stealth still place a nearly insurmountable burden on the defender.

A much bigger concern is the longer detection ranges of the SA-10 and SA-20 missiles against nonstealthy aircraft.

Those who work with stealth are steeped in these trade-offs. That’s why stealth continues to be a requirement for new systems such as the F-35, next generation bomber, and the Navy’s Unmanned Combat Air System (UCAS) demonstrator. The F-35, too, has banked on stealth as its top survivability feature.

No one is suggesting that there aren’t challenges ahead. Air defense systems, radars, and anti-stealth countermeasures will all improve over time. But so too will the low observable features of the aircraft, as can be seen in the evolution of the stealth features on the F-117, B-2, and F-22.

The next wave of enhanced survivability depends directly on making the best use of information, by sharing what stealth aircraft learn over data links that aren’t likely to be intercepted. It is certainly time to enhance the ability of stealth platforms—the B-2, F-22, and eventually, the F-35—to swap threat and mission data.

The biggest near-term threat to stealth is not in some foreign workshop. It can be found right here at home.

|

The F-35 Lightning II has stayed out of the political doghouse—so far. An early test flight of the stealthy attack fighter is seen here. |

The clear need for stealth aircraft for air superiority and global strike missions has all but dropped out of the national security discussion.

The ability to act still depends on military superiority in a desired arena. Failure to leverage America’s asymmetric advantage in stealth could quickly lead to severe limitations on where the United States military can safely operate.

Potential adversaries must be smiling at the prospect of the United States unilaterally giving up on one of its greatest military advantages.