The Air Force structured its Collaborative Combat Aircraft program to produce autonomous drones that won’t have long service lives, ensuring the service can and must move on to new systems optimized for a changing threat, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David Allvin said this week—a pathfinder for a new, broader emphasis on design rather than sustainment.

The first CCA contractors—Anduril Industries and General Atomics Aeronautical Systems—are able to keep their costs down “because we didn’t put into the mix the idea of long sustainment; of depot maintenance,” Allvin said at an Oct. 31 event with the American Enterprise Institute.

“I don’t want a 30,000-hour on engine on that thing,” he said of the CCA drones. “I don’t want it for that long. I want to be able to upgrade it to something else, without it being cost-prohibitive because we’ve already sunk so much cost” into a sustainment enterprise.

Allvin has made “agility” a defining them of his tenure as chief, and CCAs will fit that theme by making sure the Air Force is not “sunk in one particular platform for decades and decades,” he said.

With CCAs, “we want to incentivize design rather than sustainment,” Allvin said. Deciding to build CCAs as short-lived systems means “you can leverage technology and more rapidly upgrade if you change the paradigm.” He said the service plans to “broadcast that to industry,” and this approach will be central to the new Integrated Capabilities Command.

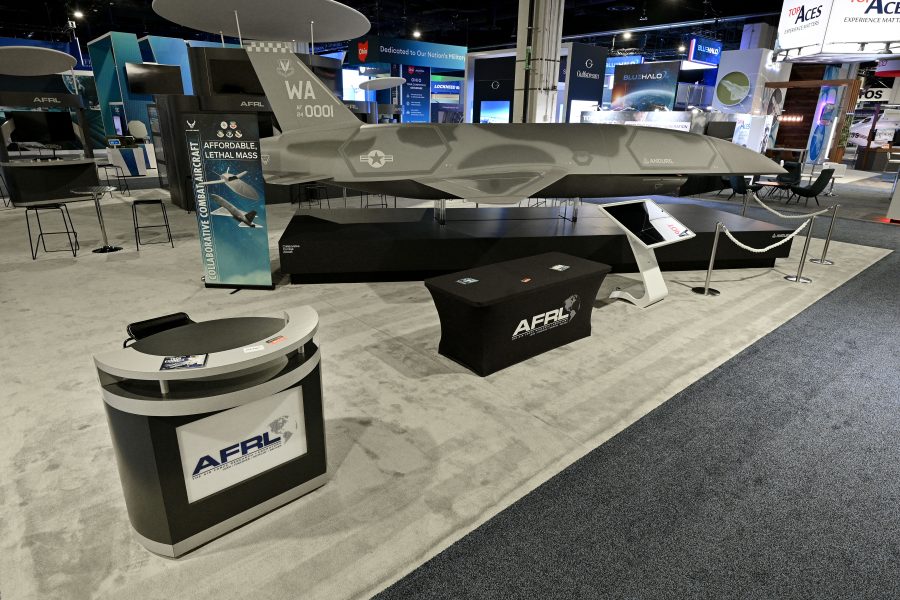

Beyond its main goals of providing “affordable mass,” and achieving air superiority in contested battlespace, the CCA program “also helps to reshape industry a bit on where we want to go as an Air Force,” Allvin said.

The Air Force sees the initial tranches of CCAs as autonomous, uncrewed aircraft that will fly in formation with crewed fighters, carry extra weapons for them, and extend the reach of their sensors. Wargames conducted over the last two years also indicate CCAs could offer a powerful support to the combat air forces if launched on their own to attack high-value targets and not directly in support of crewed fighters.

The Air Force has gone back and forth about whether CCAs should be “attritable”—meaning they are cheap enough that USAF can easily bear their loss or use them on one-way missions—or whether they ought to be more traditionally sustained, but with frequent modular upgrades. Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall has said that, at about $30 million a copy, new CCAs will not be disposable, but that the resistance to using them on one-way missions will decline as they near the end of their useful lives.

Allvin’s remarks follow on comments he made at a June AFA “Warfighters in Action” event, when he advocated for CCAs with limited operational lives. He said then he doesn’t want CCAs that will “last for 25 or 30 years,” arguing a longer service life would require more capability and thus more cost to make it worthwhile, limiting how many the Air Force can buy.

“How do we solve for agility?” Allvin asked at AEI. The answer is to change the Air Force’s “built to last” mantra to “built to adapt,” he said.

“Technology is moving so fast, the way we’re approaching Collaborative Combat Aircraft is being very strict with the requirements and saying we’re going to build for speed: speed to ramp and for the ability to be able to update … mission systems and modify as technology offers,” he said.

At the AFA event, he emphasized, “we aren’t building a sustainment structure” for CCAs. Ten years from now, the first CCA “won’t be as relevant, but it might be adaptable,” and that’s why the Air Force is mandating that the aircraft be modular, in order to keep them somewhat relevant.

Gen. Kenneth Wilsbach, head of Air Combat Command, said at an AFA event in July that he expects CCAs to be stored in a hangar—not in a box—and that training will take place with a small number of them. The rest will be kept in “flyable storage” in order to save on sustainment, but will also be “ready to go” at a moment’s notice, he said.

“They won’t fly that often,” he said, but pilots and other operators will practice directing CCAs in simulators, which will also save on sustainment costs.