In 1949, the Air Force’s new Aircraft Gunnery School opened at then-Las Vegas Air Force Base, Nev., with a group of World War II fighter pilots passing on their hard-won combat lessons to new crews.

Three-quarters of a century later, what is now the Air Force Weapons School has grown into one of the service’s premier institutions, a place where Airmen and Guardians alike can become experts in their weapons systems.

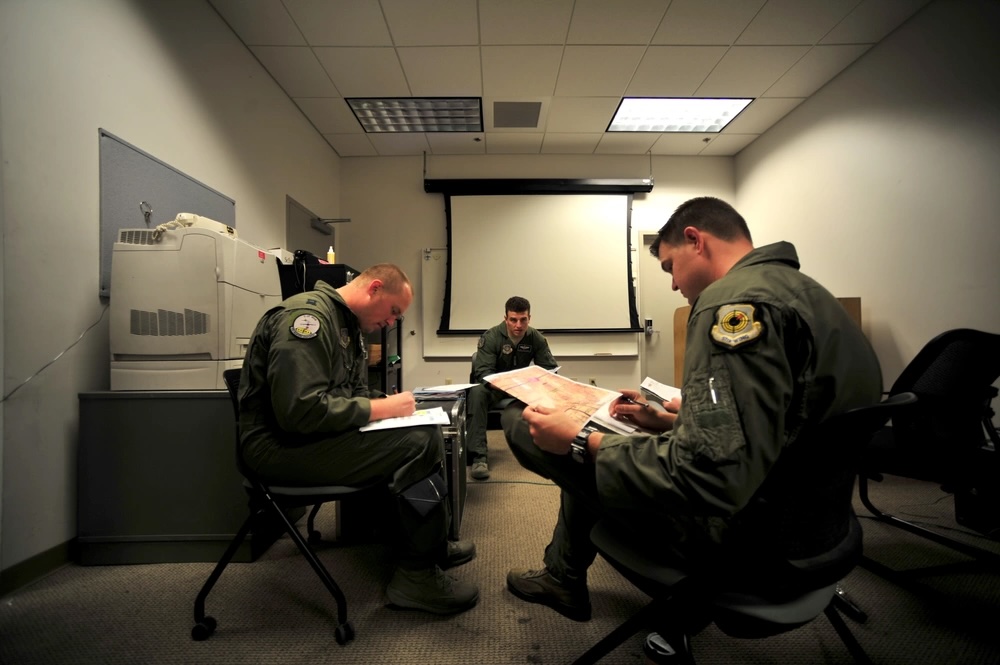

Celebrating its 75th anniversary this week, the Weapons School produces new classes of about 150 personnel every six months from Nellis Air Force Base. Initially focused on fighters, the school now teaches about bombers, helicopter search and rescue, cyber warfare, space operations, and much more, with geographically-separated squadrons hosting platform-specific classes across the country.

But despite the change, one thing has remained constant, current Commandant Col. Charles Fallon told Air & Space Forces Magazine: a commitment to keep being better.

“When you look at where we began, with very few platforms post-WWII, to where we are now, it looks like wild change,” he said. “But the one thing that hasn’t changed, from its inception until now and into the future, is that we are always going to adapt and improve. That is at the heart of what we do.”

Now, as the Air Force and Space Force prepare to fight a near-peer adversary such as China or Russia, the Weapons School is adapting too, with a greater emphasis on synthetic training environments, multidomain integration, and human performance, so that weapons officers can keep pace with the fast-moving world of military threats and technology.

“Not only are we looking to make really fantastic weapons officers, we think part of that is just making better humans,” Fallon said. “If you can make a better human, then that better human will be a better weapons officer, a better tactician. They’ll be able to answer their nation’s call to lead Airmen.”

Synthesized Success

For most of its history, the Weapons School emphasized live flight training as the way to prepare students for real-world operations. Indeed, weapons officers helped stand up the first Aggressor Squadrons: dedicated pilots who imitate hostile “Red Air” tactics to better prepare U.S. and coalition crews for combat. But in recent years, synthetic training has allowed Weapons School courses to simulate large-scale, high-tech battles that may not be possible on a real-world training range.

“When I first went through the school, it was ‘pound on your chest, we’re going to fly, we’ve got to do it live,’” said Fallon, a career F-16 pilot who now flies the F-35. “Now there has been such great advances in the synthetic environment that you can create an ultra-realistic and, in some cases, more realistic threat representation in-scenario than you could in the actual real-world environment.”

Traditional simulators taught crew members how to safely operate an aircraft, but manufacturers did not always incorporate realistic threat simulation into their design, Fallon explained. By contrast, synthetic environments often allow multiple simulators from different platforms to link together and represent threats realistically.

Fallon likened it to video games, which often fall into one of two categories: arcade or simulator. In an arcade racing game, for example, players hold a button to make the racecar go forward, while in a simulator racing game, players must shift gears and adjust for weather conditions, tire traction, and a range of other realistic factors.

“All of our simulators up until now have kind of been that arcade mode,” Fallon said. “Now we’re getting into the real simulation mode where the synthetic environment is almost imperceptible from the real world.”

While not a replacement for live training, synthetic environments help emulate threats or stand-off weapons that may be too long-range for the restricted airspace above a training range, or assets that may be too expensive to bring in more than once a year. But it also helps with the day-to-day skills Airmen and Guardians need to stay proficient.

“I can go in the sim for eight hours and those individuals can receive hundreds of reps and sets that would have taken an entire year of training live,” Fallon said.

Multidomain Masters

The push for synthetic environments occurs as warfare becomes more multidomain: the first-ever Bamboo Eagle exercise held earlier this year featured air, sea, cyber, and space operators working together in an eight day simulation of an Indo-Pacific conflict. That melding between domains is also happening at the Weapons School, where Fallon sees students from different platforms working together earlier in the six-month curriculum.

“That integration continues to push left in the timeline, and you honestly can’t start that early enough,” he said.

That was not always the case at the Weapons School, which for its first 43 years focused exclusively on fighters. That changed in 1992, with the activation of B-52 and B-1 bomber divisions; followed by HH-60 rescue helicopters, EC-130 electronic warfare planes, and RC-135 intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance jets in 1995; and a space division in 1996.

Today, the Weapons School features 21 Weapons Squadrons, focused on platforms ranging from intercontinental ballistic missiles to CV-22 tiltrotor transports. The F-35 embodies that fusion: a multirole fighter jet with cutting-edge sensors and electromagnetic warfare systems. Almost 70 percent of the F-35 Weapons School syllabus involves some sort of integration with another platform, Fallon said.

“That’s a wild change from other platforms in the past, and we would assume every platform that onboards from here on out is going to be very typical of that,” the colonel said.

The mind-melding culminates in the three-week Weapons School Integration (WSINT), the capstone element where students work together to plan and execute “every aspect of air, space, and cyber combat operations,” according to the Air Force.

The growing emphasis on integration also reflects that the Weapons School, never known for being easy, may become even more demanding of students, who are already expected to be Ph.D.-level experts in their own platforms upon graduating.

“It was a real shock for someone who’d aced everything to date to consider failing a formal course,” wrote retired Lt. Col. Dan Hampton about his experience at Weapons School in his 2012 memoir “Viper Pilot.” Besides a heavy flying schedule, he and his fellow students also had to juggle hundreds of hours of academics covering aircraft weapons, systems, and tactics, write a graduate-level paper, and then present it to their instructors.

“I used to fall asleep standing up in the shower at the end of the day,” Hampton wrote. “It sucked. I loved it.”

Still, part of the expectation at the Weapons School is to raise the standards, “so that every single class is more difficult than the class prior to it,” Fallon said.

“As our understanding of the pacing challenge continues to evolve, we continue to add on,” he said. “All the things that we have asked our graduates to do for the past 75 years, that’s just the norm. And then anything new is a growth on top of that. The old stuff doesn’t go away, there’s nothing that comes off the plate.”

The Weapons School plate has more on it now than ever before, but new advances in human performance could help students consume more and digest it faster to keep pace.

Human Performance

The Weapons School is often “the nexus of the latest and greatest technology and what things you can do with that technology,” Fallon said. “But for right now, it’s people that operate all of our technology, and so that’s where we really need to lean in and invest.”

Recent efforts include taking lessons from science and academia on how people cognitively behave and receive information. For the past year and a half or so, the school hired a contractor to perform cognitive brain mapping on students and instructors, examining their brain waves, stress levels, and their abilities to learn and adapt. The data so far hints that future syllabi could benefit from having time off or “very targeted recovery, rather than just ‘Hey, you’re gonna fly every single day for five days,’” Fallon said. “And then at the end of the week, we wonder why someone’s not getting better.”

Several hundred students and instructors are also tracking their sleep and daily routines through wearable technology, which helps them better understand how to perform at their best.

“We can’t continue to burn people out into the red and then wonder why they’re not getting it,” Fallon said. “We need to allow them to get into what we call a flow state, so that they can actually perform at their peak. Then we need to proactively work that into the syllabus, which is something that’s never been attempted here before.”

Beyond making sure students perform at their best in Weapons School, Fallon also wants graduates to keep improving long after they put on the school’s iconic patch.

“The real problem is once you put that patch on your shoulder, training in the Air Force literally stops,” Fallon said. “There are no more upgrades that I can put you in, there is no formal course I can send you to to get you more training in your platform.”

The default assumption, he explained, is that the patch-wearer is at the top of their game and the best of the best.

“My question is just, can you make them better?” the colonel asked.

Synthetic training could play a role by remembering an individual’s weak areas from past experiences, then targeting those whenever they hop in a simulator. The technology is not there yet, the colonel said, but once it is, it could ensure weapons officers retain their edge.

Inflection Point

The Air Force Weapons School has a 75-year tradition of excellence, one that Fallon is reminded of every time he walks through the front door and is greeted by a statue of Brig. Gen. James “Robbie” Risner, the Korean War ace who was shot down during the Vietnam War and helped keep up the spirits of his fellow prisoners of war at the infamous “Hanoi Hilton.”

“That is definitely a visceral thing that physically hits you in the face every single morning when you walk in, and it really means something,” Fallon said.

Though Risner was not a weapons officer, every year a graduate receives the Risner Award for embodying the Weapons School’s values: humble, approachable, and credible, and for doing something “of great credit for the community and represents the patch the best,” Fallon explained.

The Weapons School’s heritage will be on display May 17 during a celebration of the school’s anniversary. In a separate event, the base will also rename the headquarters complex for the 57th Wing and 99th Air Base Wing the Gen. John P. Jumper Headquarters Complex after the 17th Air Force Chief of Staff who served as the Weapons School flight commander from 1974 to 1977.

Jumper will attend the events, as will Air Combat Command head Gen. Kenneth Wilsbach and U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown, himself a former Weapons School commandant.

That celebration of the school’s heritage is well-timed, Fallon said, as the Air Force prepares for possible conflict against China or Russia on a tight budget and short timelines. Weapons officers from years gone by also had to adapt to challenges with limited resources, and “we can do that too,” the colonel said. “We can be those people.”

“This is a great inflection point for our institution and it is probably happening at the exact right time,” he said.

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated with information from Nellis Air Force Base clarifying which building will be dedicated to Gen. John Jumper.