Airmen recently tested new chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) gear that would replace gas masks and hoods designed decades ago for aircrew aboard transports, tankers, and other aircraft that don’t feature ejection seats.

The new gear was rolled out at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base on June 5 and announced in a press release a month later.

“We felt that we were overdue an update,” said Master Sgt. Diego Cancino, Aircrew Flight Equipment (AFE) flight chief with the 445th Operations Support Squadron, in the press release. “The new mask system is a breath of fresh air for both AFE as the equipment maintainers and aircrew as the end user.”

The old Mask Breath Unit-19P Aircrew Eye and Respiratory Protection (AERP) was no favorite among Airmen. “It’s like flying a plane while wearing a thick garbage bag over your entire body,” said one C-17 pilot, who spoke to Air & Space Forces Magazine but asked not to be identified. “It’s hot, fogs up, is a major situational awareness drainer and in my opinion incredibly unsafe to use in flight.”

That pilot has yet to try the new M69 system. But Tech Sgt. Conner Odom, of the 60th Operational Support Squadron at Travis Air Force Base, Calif, was elated after it trying it in December. “This equipment is light-years ahead of the legacy AERP,” he said.

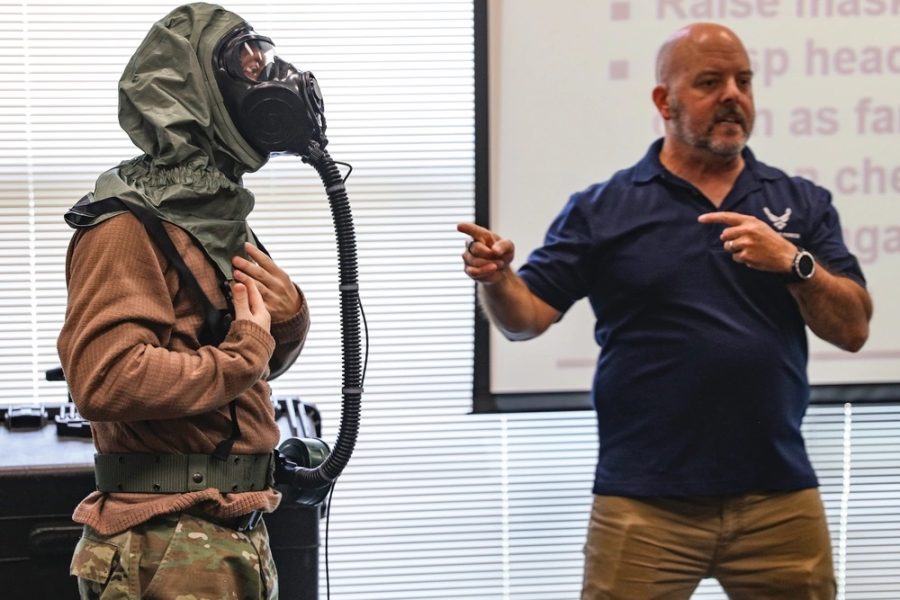

Officials say it is cooler to wear, less bulky, and has a better field of vision. It’s also much easier to put on. Odom said aircrew can spend 10 minutes wrestling their way into the old full-body AERP, but it takes just 10 seconds to don the new M69 mask and only two minutes to put on the full suit. “In a CBRN environment, there isn’t going to be a lot of time to react,” Odom said, so speed is crucial.

Aircrews first started trying the M69 about 2018, when HH-60G Pave Hawk and UH-1N Huey aviators tested it at Aberdeen Proving Ground, Md. In 2019, C-130J aviators at Little Rock Air Force Base, Ark., conducted operational testing. At the time, Tech. Sgt. Benjamin Leis, of Little Rock’s 19th Operations Support Squadron, said “I think we’re in a far better situation for aircrew protection and the ability to maintain operations in contested environments with this piece of equipment.” He also thought it would be easier to teach others to use.

Now, four years later, 20,273 masks have been fielded and the Air Force will soon declare full operational capability, perhaps by 2024, according to a Wright-Patterson release. That sets “a new standard with system deployment,” said 1st Lt. Gunnar Kral, lead engineer for Joint Aircrew CBRN Protection.

But What About the Planes?

Yet while the M69 system better protects aircrew, what’s less clear is how to protect and, if necessary, decontaminate exposed planes. The C-17 pilot who spoke with Air & Space Forces Magazine flagged this issue as one of ongoing concern.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Joint Biological Agent Decontamination System (JBADS) gained favor for decontaminating aircraft against the virus. Ground crews built temporary shelters around the aircraft and then pumped it full of hot air, killing any lingering virus.

“JBADS uses high temperatures of 140 to 180 degrees Fahrenheit and controlled humidity levels to eliminate contaminants in an enclosed environment without harming aircraft systems,” the Air Force Research Laboratory wrote of JBADS during the pandemic. “The system enables full decontamination of an entire aircraft.”

But chemical, radiological or nuclear exposure may not be affected by that treatment. JBADS also requires specialized equipment not widely available to most commands. Air Force doctrine recognizes that CBRN exposure could “significantly degrade the rate of force deployment” as aircraft are removed from use, according to Air Force Doctrine Publication 3-40, “Counter Weapons of Mass Destruction Operations.” “Until large-frame aircraft decontamination is technically feasible, contaminated aircraft should be segregated from the airlift flow.”

If aircraft have to land at contaminated airfields, commanders may need to establish a site for crew and cargo in between clean and contaminated aircraft, a necessity that would delay time-sensitive deliveries and may not be feasible except in emergencies. Host nations may also object to landing contaminated aircraft in their territory.

“Until internationally recognized standards and legal requirements for acceptable decontamination levels are established, nations may deny transit and overflight rights to contaminated aircraft or cargo,” the publication said.

The C-17 pilot wondered what circumstances might require flying into an exposed area.

“I cannot foresee a scenario,” he said, “where the Air Force would knowingly sacrifice a $220 million jet by purposely flying it into a contaminated environment.”