New storms may already be forming in the Caribbean and tropical Atlantic, even as rain soaks the East Coast in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene last week, which killed at least 130 people and closed two major Air Force bases.

That means hurricane season is far from over for the 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, an Air Force Reserve unit stationed at Keesler Air Force Base, Miss.

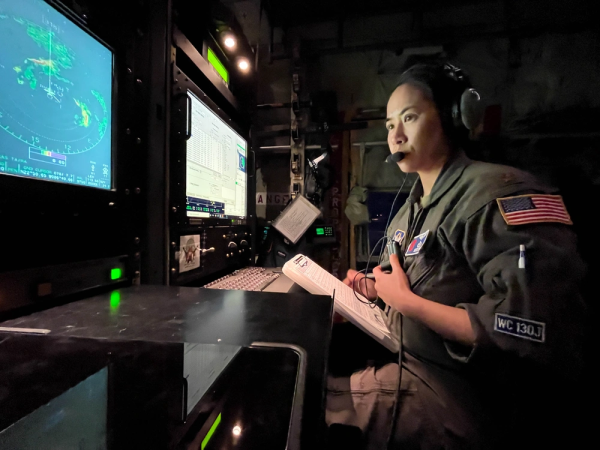

Better known as the Hurricane Hunters, the squadron flies into storms to collect atmospheric data that help scientists at the National Hurricane Center (NHC) predict the size of the storms and where they will make landfall, which in turn helps decision-makers make calls such as evacuation orders.

Their work makes a big difference, increasing weather model accuracy and hurricane track forecasts by 20 percent. That saves lives and money; it costs at least $1 million to evacuate a mile of coastline, so it helps when planners have a better sense of where to focus safety efforts.

Helene was a case in point. The 53rd WRS flew nine missions into the storm from Sept. 23 to 26, according to a press release.

“[W]e have been working around the clock to provide data for NHC forecasts,” the squadron wrote on Instagram as Helene approached Florida.

The squadron’s work is particularly important for rapidly intensifying storms such as Helene, which grew from a tropical storm into a Category 4 hurricane in just 64 hours.

“Rapid intensification is a phenomenon that is difficult to forecast and forecast models still have a hard time predicting it,” Capt. Amaryllis Cotto, an aerial reconnaissance weather officer, said in the release.

“This is a feature that Hurricane Hunters can analyze while flying the system, providing real-time insight of the storm,” she added. “By relaying how well or fast it’s developing, NHC forecasters then have the chance to make quick updates on their watches and warnings and quality check the current forecast trends.”

Bargain Hunting Hurricanes

But providing that data requires aircraft, personnel, and funding, and the 53rd WRS is stretched thin covering a longer hurricane season and an increasingly busy winter season. The squadron has seen an 18 percent increase in demand flying hurricanes since 2018, Air & Space Forces Magazine reported in May.

When hurricane season wraps up in November, the 53rd WRS switches to atmospheric rivers: bodies of water vapor flowing through the skies over the Pacific Ocean that can carry massive amounts of potential rain, snow, and flooding across the West Coast. Historically, winter was a chance for the squadron to recuperate after hurricanes, but the demand for winter missions has climbed 606 percent since 2018, with no new resources to meet it.

“The resources we’re working with today were established and set in 1996 and no significant changes have happened since then,” Maj. Chris Dyke, another aerial reconnaissance weather officer, said in April. “At that point it was resourced for a six-month hurricane mission. We are now a 10-month operational mission and a two-month road show. … To be honest, it’s not enough time for the aircraft.”

In last year’s defense spending bill, Congress required a report from the Air Force on whether the 53rd WRS has enough resources to meet requirements. The Air Force completed the report in April and Air & Space Forces Magazine obtained a copy late last month. The report lays out in greater detail why the squadron’s resources are insufficient today and will be even more so in the near future.

“Looking ahead to 2035, projections indicate a consistent rise in operational demands for weather reconnaissance,” Lt. Gen. John P. Healy, chief of the Air Force Reserve, wrote at the top of the report. “Despite the impressive contributions of the 53rd WRS, the report identifies substantial challenges due to resource constraints.”

The 53rd WRS’ requirement to fly hurricanes falls under the National Hurricane Operations Plan, which lays out that Air Force weather reconnaissance forces must provide 24/7 coverage of current or potential tropical cyclones threatening the U.S. or its interests on both coasts from up to three locations simultaneously.

The minimum force for covering one storm 24/7 is three aircraft, 54 aircraft maintainers, 18 aircrew members, and 23 support personnel, the report said. But as storms approach the mainland, that amount goes up by one aircraft, 13 aircrew, and three support personnel. That means to conduct operations any time during hurricane season (June 1 through Nov. 31), the squadron needs 10 operational and available aircraft, 164 maintainers, 67 aircrew, and 72 support personnel, the report said.

At first glance, the 53rd WRS appears to hit most of those numbers, with resources allocated for 10 WC-130J aircraft, 278 maintainers, 100 aircrew, and 57 support staff. But the number of missions keeps rising, and not all the squadron’s allocated people or planes are available to carry them out.

“The unit has averaged just above 50 percent available manning due to position vacancies, members in training, and members not medically available,” the report read.

Further more, only 110 of the squadron’s maintainers are authorized for mission generation, but the standard for C-130Js is 54 maintainers for three aircraft at each location, the report said. That means the squadron can support only two locations even if all its authorizations were available at all times.

“Given current challenges and compounded by the anticipated future growth in demand, we are not positioned to be able to fully support NHOP requirements,” the report states.

The squadron’s aircraft are in a similar situation. When it adopted the WC-130J in 1999, the 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron was among the first units in the Air Force to fly the ‘J’ model, the latest version of the venerable C-130 aircraft. But 25 years later, the fleet is feeling the effects of a quarter century of rough skies. The average availability aircraft for the squadron was 65 percent, according to the report, with at least one aircraft in long-term depot maintenance and another in short-term maintenance at any given time. That leaves just eight available aircraft to handle requirements.

“Because it’s aging, it gets worse each year, and so the vast majority of your non-mission capable time is scheduled maintenance, and that increases each year,” Col. William Magee, commander of the 403rd Maintenance Group, said in April.

Hungry Winters

Why the rise in demand? Scientists need to identify tropical cyclones earlier in their development and provide more persistent coverage to spot changes in storm track and intensity, the report said, and advances in weather model capability make that coverage even more important. Mother Nature also has a vote, with the squadron expecting a bump from 15 to 16 storms per year today to 18 storms by 2035.

The squadron faces similar demands and challenges in the winter, which is covered by the National Winter Season Operations Plan (NWSOP). Like with hurricanes, the NWSOP requires 24/7 coverage of potential environmental threats on both coasts from up to three locations at the same time.

Fulfilling that requirement for one location at any given time requires the same minimum package of 3 aircraft, 54 maintainers, 18 aircrew, and 23 support personnel, the report read, but being ready to handle more than one location from Nov. 1 to March 31 takes more people than the 53rd WRS might have available at any given time.

The number of winter flying hours has gone up more than 600 percent since 2018, with Airmen flying missions all over North America. The squadron expects its winter storm flights to bump up from 50 today to 65-70 by 2035.

“Given current challenges and anticipated future growth in demand, we are not positioned to be able to fully support NWSOP requirements,” the report states.

Then there are the dropsondes: the small cylinders which crew members drop out of the aircraft on a mission. Suspended by parachute, the dropsondes collect atmospheric data and transmit it to the aircraft as they descend through the storm. But as demand for weather reconnaissance has surged, so as the 53rd WRS’ use of dropsondes: the squadron burned through 1,796 this past year (868 for winter missions, 928 for hurricanes) for a total of $4 million when including training, the report said.

Though Congress provides regular budget increases for dropsondes, the squadron said it will need even more to keep pace with demand.

When It Rains, It Pours

Beyond its hurricane and winter requirements for the homeland, the 53rd WRS is also seeing more demand from U.S. European Command and U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. For example, tropical cyclones “have been identified as the most significant environmental threat” across INDOPACOM, according to the report, particularly from July through December, which overlaps with both the hurricane and winter seasons.

That timing “would drive a significant increase to the demand already placed on the mission,” the report read. “Based on the currently limited resources of the 53 WRS (aircraft, flying hours, personnel and dropsondes), if these requirements were added, the mission capability would drop to approximately 25 percent.”

The squadron already has to decline some missions; Dyke recalled a moment last year where the 53rd WRS pulled aircraft out of the Caribbean island of St. Croix and sent them back to Keesler to track Hurricane Idalia, which was deemed the more important storm.

“That was an example where we’re asking the hurricane center, ‘OK, pick and choose, what’s your priority?’” he said in April. “There are impacts from the one we don’t fly. We’re talking about potential impacts to stateside readiness, homeland defense.”

Congress did not require the Air Force to estimate how many more aircraft, personnel, and other assets it would need to meet growing requirements, but it was clear from the report that today’s mix is not enough.

“Despite these expanded responsibilities and significant extension of the operational season, the number of aircraft in the 53 WRS has remained constant, challenging their ability to cover these diverse and increasing demands,” the report read. “As the frequency and severity of weather-related disasters rise, alongside the growing global strategic concerns, the demand for reliable weather data, especially in data-sparse regions has never been more critical.”