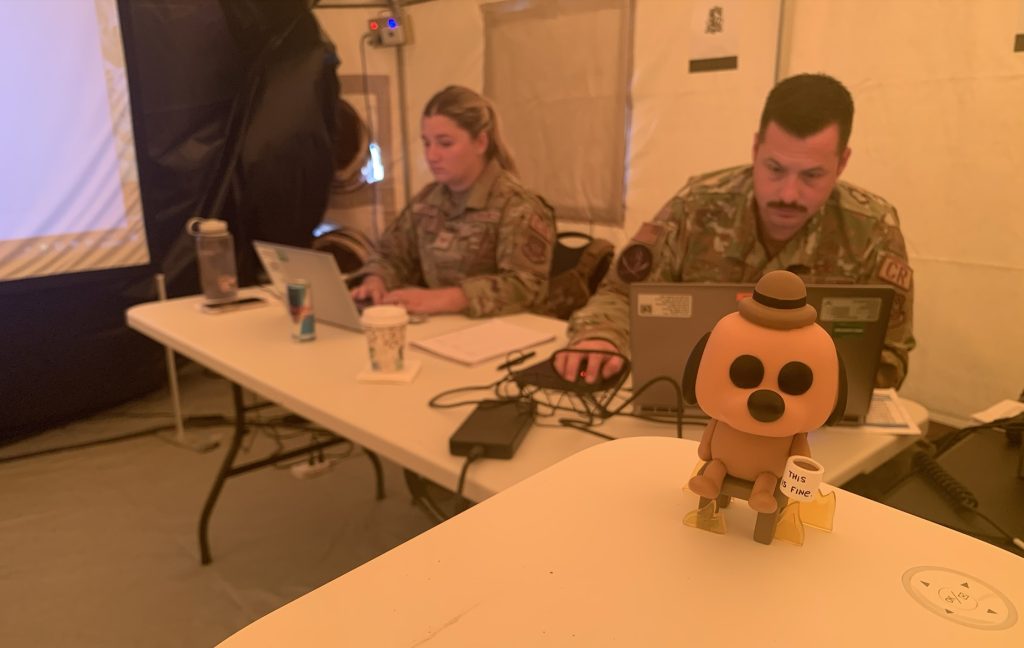

MOJAVE, Calif.—Like a shrine in a temple, the plastic dog sat atop a projector in the center of the tactical operations tent for the 621st Contingency Response Squadron, reminding the Airmen inside that they could still accomplish the mission despite challenging circumstances.

The plastic totem is a reference to a popular meme where a dog in a bowler hat tells itself “this is fine” despite the room burning down around it. The meme is worthy of contingency response, or CR, which opens up air bases in austere and unpredictable conditions.

“We wear this CR tab very proudly,” said squadron commander Lt. Col. Andy Nation, one of the ‘Devil Raiders’ of the 621st Contingency Response Wing. “But every single time we exercise and conduct operations, you will find chaos everywhere. We find solutions to bring things together and resolve everything. And so we’ve come to adopt CR as meaning ‘chaos resolved.’”

CR had plenty of chaos to resolve at Bamboo Eagle, a new series of exercises where combat aircraft operate out of small air bases scattered across the West Coast instead of large ones that present juicy targets for long-range missiles. The concept is called Agile Combat Employment (ACE), and it requires working closely with mobility aircraft—the transports and tankers that move bomb carts, generators, and other equipment for re-arming and refueling combat aircraft.

“Air Combat Command does not have a heavy port footprint, so when they’re trying to establish their mission generation force elements [MGFEs], they need someone to catch that equipment that comes on cargo aircraft: all the things they need to bed down a base,” Nation explained.

Bedding down a base sounds simple, but it hinges on the nitty-gritty details that make airpower possible: are the bomb carts and power generators loaded properly so that C-17s can safely fly them to another airfield? Once it gets there, are there enough forklifts to quickly download cargo before the C-17 can be targeted by a missile? If the airfield is targeted, how do Airmen request C-130s to take them and their equipment to a new one?

Answering those questions is where contingency response comes in. CR’s “bread-and-butter” is opening and closing air bases to support wartime or humanitarian efforts, the lieutenant colonel said. Doing so usually requires moving in small, maneuverable groups, but CR is going even smaller and more agile in preparation for possible conflict with China, where the vast distances of the Pacific Ocean will make space aboard America’s limited airlift fleet a scarce resource.

“There’s only so many C-17s, and we have to move the Army,” said Lt. Col. Andrew Morris, director of operations for the 621st CRS.

Status Quo

CR missions typically go like this: first an airfield assessment team of about eight Airmen equipped with Humvees or ATVs ride a C-130 out to an airfield to gauge its suitability for military aircraft. Next, either a Contingency Response Team or a Contingency Response Element shows up to stand up the air base. A CRT typically involves about 25 Airmen, a few vehicles, and a forklift, all of which can fit on three C-130s or a single C-17, and they can operate one shift a day on a limited airfield for about 45 days.

A CRE is intended for larger operations, with about 108 Airmen, three forklifts and other vehicles, and enough tents and supplies to operate an airfield for two shifts a day for up to 60 days before typically handing it off to more permanent forces. But the CRE footprint is big, requiring five C-17s or 12 C-130s.

Both models have had great success in the past: CR played a crucial role shutting down U.S. air bases in Afghanistan in 2021 and, just a few months later, briefly turning Kabul’s Hamid Karzai International Airport into one of the busiest airports in the world as 124,000 refugees streamed out of the country.

During unrest in Haiti in April, the 621st CRW experimented with a new formation called contingency support elements (CSEs), bare-bones teams that can hop off a single C-130, support airfield operations for a limited time, then hop back out to a new location. For the Haiti response, a CRE stayed in Joint Base Charleston, S.C. while CSEs of about 20 Airmen flew down to Port-au-Prince, worked the airport, then flew back at night.

“It was a short-term solution to ‘hey, what is the bare minimum we need to get to the airfield, operate it, download the aircraft, and then get out of there each day,’” said Maj. Jacob Draszkiewicz, commander of the 521st CRS response element at Bamboo Eagle.

At Bamboo Eagle, each CR squadron operated out of a “hub” where they placed their tactical operations center. For the 621st, the hub was Mojave Air & Space Port, Calif., while the hub for the 521st was about a 30-minute drive east at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. Each hub oversaw three or four smaller airfields, called spokes, across the state.

The squadrons sent CSEs of about eight Airmen each from the hubs to the spokes, where they would catch aircraft, unload gear, and either stay overnight or jet out again to return to the hub or work another spoke, depending on the mission. Over the course of Bamboo Eagle, CSEs helped turn F-16s at Victorville, Calif., moved bomb loaders and other equipment between spokes, and responded to last-minute taskings when well-laid plans fell through.

“You don’t have as much capability with that CSE, but you’re tailoring it to just do what you need to do at that airfield, so you can retain other forces back in the hub to task elsewhere,” Draszkiewicz explained.

Swiss Army Airmen

CSEs are highly modular so they can respond to different missions. Some may have more aerial porters to focus on offloading cargo, while others have more Security Forces Airmen who can protect troops on the ground. But the concept fails without each Airman picking up skills outside their usual specialty, a concept now dubbed “mission-ready Airmen.” While it may be a new idea for many Air Force units, it’s old hat at CR squadrons.

“We train every day to be able to plug in holes with someone who maybe was not specifically trained to do that thing,” said Nation. “So a pilot can spin up that generator, or plug in these power distribution systems, or go do some special fueling operations.”

Beyond mastering different skills, being mission-ready involves preparing to improvise solutions for unexpected problems. During the Kabul airlift, CR Airmen jerry-rigged snow plows to clear the airport ramp of trash, put down lights for guiding aircraft at night when the generators went down, and hot-wired abandoned cars to get around the airfield faster.

Fast-forward three years to Bamboo Eagle, and CR was back at it. Morris, a C-130 pilot by training, guided a contractor through generator reset procedures over FaceTime to get air conditioning in the TOC back online in 100-degree heat, while other 621st Airmen borrowed a nearby munitions squadron’s forklift to support an incoming two-ship of C-130s.

“Now we just doubled our throughput to make sure the aircraft don’t get delayed,” Morris said. “It’s little things like that which I think we’re very strong in: ‘hey there’s a problem and we’ll find a way to solve it.’”

Turbulence

To make hubs and spokes work, the CR squadrons are experimenting with new communications gear that lets them share more information over greater distances more securely. These include MPU-5 “smart radios,” ATAK and WinTAK smartphones, and Starshield, a military adaptation of SpaceX’s Starlink satellite network. Starshield and the MPU-5s give the CR “instant internet,” Nation said.

“Instead of your line-of-sight PRC-152 radio where I’m talking to somebody just across the flight line, this … sets up a mesh capability, so every MPU-5 is a repeater, and the more of them you have, the stronger the whole signal is in that area,” he said. “As long as you have connectivity to the internet in another location [it’s] as if you were right next door to them.”

But not all mobility aircraft enjoy the same connectivity, a point which Air Mobility Command boss Gen. Mike Minihan wants to address through his “25 by 25” initiative. For example, some aircraft can call CR Airmen hours away via satellite phone, while others are limited to high-frequency radios or even shorter-range devices.

The mix of communication systems does not stop CR, which will find a way to adapt, Morris said, but it meant locating aircraft for planning purposes was a challenge throughout the exercise. On the other hand, CR has to be prepared to operate without communications systems if they are spoofed or jammed by adversaries, Nation pointed out.

A CSE from the 521st put that skillset to work when they were tasked to a spoke with just a few hours’ notice. Ideally, CR Airmen know what aircraft they’re taking on a mission, how long they’ll be there, where the aircraft is parking, and what to do if things don’t go according to plan, but there wasn’t time to sort out such details, Draszkiewicz said. Still, they had their training and their commander’s intent, so the Airmen got to the spoke and helped turn fighters as required.

“Working through those challenges—delays, maintenance issues, things like that—is what really prepares the team,” the major said.

Another challenge came from working with combat aircraft units, a first for many mobility Airmen and vice versa. At Bamboo Eagle, the CR squadrons fell under two Air Combat Command wings: the 23rd Wing for the 621st CRS and the 9th Reconnaissance Wing for the 521st CRS. The combat wings served as Air Expeditionary Wings, controlling fighters, tankers, airlift, and other assets from the hubs at Mojave and Edwards.

“This is the first exercise I’ve been on where AMC and ACC are directly integrated, which is awesome, but with that comes some hurdles as to be expected,” Draszkiewicz said.

For example, ACC Airmen may not know what website to go to and what form to fill out for requesting airlift; what equipment needs to be at an airfield to offload cargo; or how many Airmen are needed to operate it. CR brought their colleagues up to speed, a familiar situation since CR often works closely with the Army and has to translate Air Force for Soldiers.

“It would seem like Air Force could talk to Air Force, but that’s not realistic, and that is evident in this exercise,” Draszkiewicz said. “We’re working through it.”

The integration extended to the spokes, where fighter and airlift maintainers swapped insight for fixing each other’s aircraft. Recently, CR units have started adding fighter and helicopter maintainers to their ranks to prepare for “any contingency situation thrown at us,” said Tech Sgt. Christopher Hokanson, a C-130 crew chief by training.

“This is actually one of our first exercises where we’re incorporating all those different maintainers and teaching them what we do, and they’re also showing us the fighter and the helicopter aspects that we heavy crew chiefs are not familiar with,” he said.

Building the Narrative

Draszkiewicz said afterwards that the exercise was overall “a huge success,” and that CR is at a 90 percent solution in terms of figuring out CSEs. One area left to resolve is laying out guardrails for how long CSE members ought to work before resting, “just to make sure that we’re still operating safely and prepared to do the mission at the same time,” Draszkiewicz said.

The unpredictable nature of CSE work means it can be difficult to keep regular shifts, especially when communications trouble means that a C-130 might appear overhead at any minute. But setting guardrails for shifts isn’t something to be left open-ended, the major said.

In a way, CSEs are nothing new: Draszkiewicz pointed out that the U.S. island-hopped all over the Pacific to win World War II. Exercises like Bamboo Eagle serve as refreshers on the tiny details that make such movements possible. It also reminds the Air Force writ large that no one fights alone.

“It just built the narrative … the Air Force has many different entities who do different things, but not one can do everything by itself,” he said. “It takes collective will, knowledge, and ability to move the pieces around where they need to go in order to accomplish the mission.”