It was Easter Monday, 1966, in Vietnam. The US 1st Infantry Division was pushing through the dense jungle east of Saigon in search of the Viet Cong battalion known as D-800.

Three rifle companies–Alpha, Bravo, and Charlie–of the 2nd Battalion of the 16th Infantry Regiment were conducting the search near the village of Cam My. As the day wore on, the unevenness of the terrain led Charlie Company away from the other two.

Early that afternoon, Charlie Company flushed a Viet Cong platoon, killed several VC, and pursued the others deeper into the jungle.

The Americans knew from intelligence reports that D-800 was a first-line battalion with 400 troops and a backup force of women and children. Charlie Company had 134 troops.

The mismatch was of little concern, since the soldiers expected to be reinforced if they encountered the enemy in strength.

“What we didn’t know on Monday, April 11, was that we were walking straight into D-800’s base camp, and that the undergrowth was so utterly dense in this part of the jungle that we couldn’t be reinforced easily,” said John W. Libs, who in 1966 was a first lieutenant leading C Company’s 2nd Platoon.

By mid-afternoon, D-800 had Charlie Company isolated and encircled. The VC sprang the trap, and the fighting grew desperate. Of the 134 men who went into the jungle that day, all except 28 would be either wounded or killed before the battle was over.

The nearest clearing where the Army could land a Huey medevac helicopter was four miles away, so as the casualties began to mount, a call went to Det. 6, 38th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron, at Bien Hoa, 20 miles northeast of Saigon. The Air Force’s HH-43 helicopters could lower a hoist to the jungle floor.

Two Helicopters Respond

At 3:07 p.m., Bien Hoa got the call to go from the search-and-rescue control center in Saigon. The Army was reporting at least six casualties. With that many wounded to bring out, two helicopters would go.

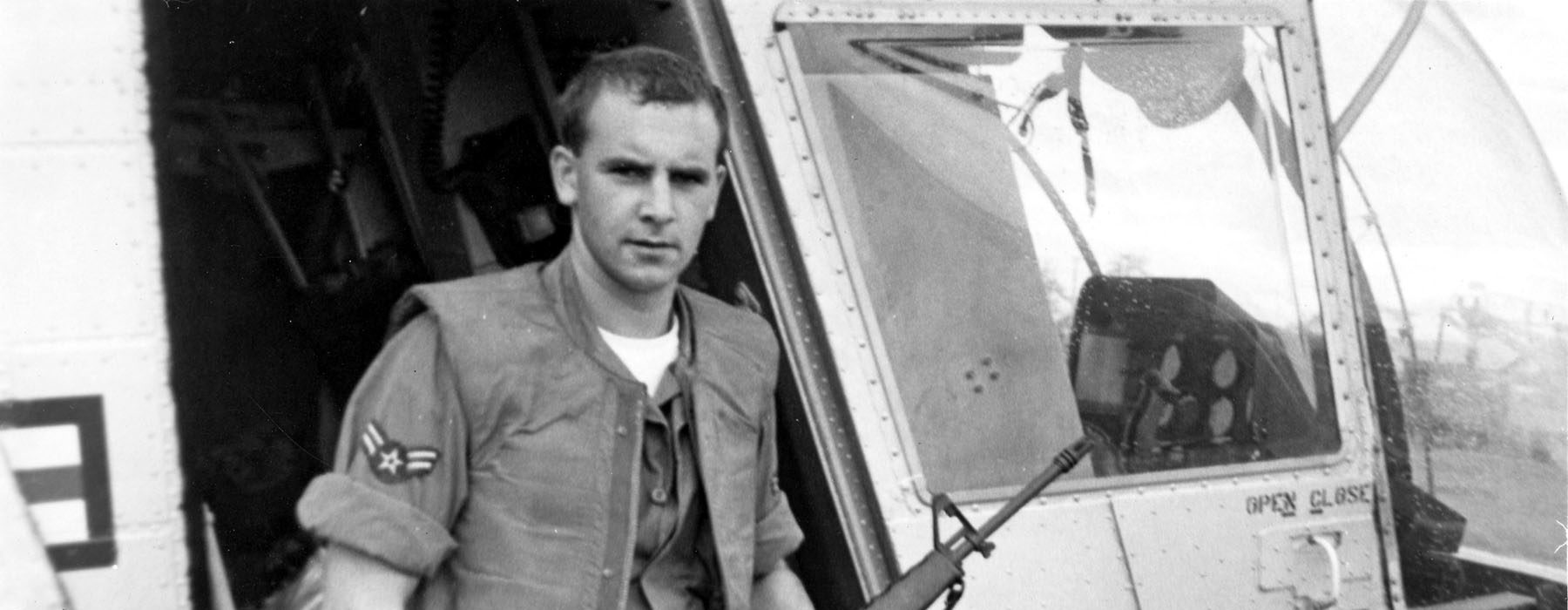

A1C William H. Pitsenbarger was in the alert trailer when the call came in. He would be the PJ-the Pararescue Jumper-on the second crew.

He spoke briefly with A2C Roy Boudreaux, one of the three airmen with whom he shared a cubicle in a Quonset hut. Pitsenbarger told him they were going to help an Army company in trouble. “There’s about a million VC in the area,” he said. “I don’t have a good feeling about this one.”

Pitsenbarger was 21 years old. He had been in Vietnam for eight months.

He had not yet completed his first enlistment in the Air Force. As a PJ, he was both a medic and a survival specialist. He had been through Army jump school at Ft. Benning, Ga., and qualified by the Navy as a scuba diver. He had also been to Air Force “tree jump” school, training that included three parachute jumps into a forest, wearing tree jumping suits.

He planned to leave the Air Force when his hitch was up. He had applied to Arizona State, where he hoped to study to become a nurse.

Search-and-rescue missions did not happen every day, but when they did, the choppers often flew multiple sorties, searching the jungles or shuttling between battle zones, bases, and field hospitals. Pitsenbarger had five oak leaf clusters to his Air Medal, each representing 25 flights over hostile territory, and more clusters were pending.

In March 1966, Pitsenbarger had descended from a helicopter into a burning minefield to rescue a Vietnamese solider who had stepped on a land mine. For that action, he had been recommended for the Airman’s Medal. It would be awarded posthumously.

When he was growing up in Piqua, Ohio, he had been called “Bill,” but to his colleagues at Bien Hoa, he was more often “Pits.”

Problems With the Pickup

The first rescue helicopter, Pedro 97, flown by Capt. Ronald Bachman, was airborne at 3:12 p.m. Pitsenbarger was on Pedro 73, which was close behind.

The first of the formidable HH-3 Jolly Green Giant rescue helicopters had recently arrived in Southeast Asia, but Bien Hoa did not have any of those. What the detachment there flew was the HH-43F Huskie-known everywhere as “Pedro”-the small utility helicopter that hovered over the runway, prepared for fire suppression, when an airplane landed with a gear malfunction, a warning light, or some other problem or emergency.

It performed that role at Bien Hoa, but it had also been adapted for jungle rescue. In that configuration, it carried two pilots, a crew chief, and a PJ, plus the forest penetrator, a litter, a stretcher, and medical kits.

The pilot of Pedro 73 was Capt. Hal Salem. The detachment commander, Maj. Maurice Kessler, was flying as copilot. Capt. Dale Potter, regularly the other pilot on the crew, had gone to Saigon to pick up some litters. Beside Pitsenbarger in the rear seats was A1C Gerald Hammond, the crew chief.

It took the two helicopters about half an hour to reach the battle. Charlie Company had marked its location with colored smoke.

All around them was triple-canopy jungle, the tallest trees reaching up 150 feet. However, there was a place where the trees topped out at 100 feet. Beneath that, thick brush grew from the ground to about 30 feet up, but there was a hole in the canopy just large enough for a Stokes litter-essentially a wire basket-to get through.

Bachman maneuvered the first helicopter, Pedro 97, into place. He hovered below treetop level. The opening was so tight that the whirling helicopter blades passed within five feet of the trees.

Pedro 97 lowered its litter, picked up the first casualty, then pulled back to transfer him from the Stokes litter to a folding litter. Pedro 73 moved into the hole and made the next pickup, but it did not go smoothly. The wounded soldier was in a makeshift stretcher, crafted from tree limbs and a poncho, and the ground party had put him, stretcher and all, into the litter. The extraction was precarious because the soldiers had not strapped the wounded man in.

The litter snagged repeatedly on the way up, and the stretcher could not be brought all the way into the helicopter. It was a struggle to get the soldier aboard. The pickup took far too long to complete, with the helicopter hovering there as a provocative target for ground fire.

“We had no direct communications with the people below, except through hand signals,” Salem said. “We really couldn’t advise them on how to speed up the process or to help them evaluate the extent of the injuries. Hopefully, some of the wounded could be sent up on the forest penetrator, which was much faster but certainly couldn’t be used for hoisting the critically wounded.”

Bachman’s crew took another soldier aboard, and the two helicopters took the wounded to an Army hospital at Binh Ba, eight miles to the south.

Pits to the Ground

When the choppers returned to the jungle site, Pitsenbarger asked the pilot to put him on the ground.

“Once I’m down there I can really help out,” he told Salem. “I can show those guys how to rig the Stokes litter and load it right. It will be much faster, and you can put more people in the bird.”

Salem thought about it, discussed it with the crew, and decided that Pitsenbarger was right.

“We wished Pits good luck,” Salem said. “I maneuvered the helicopter into the pickup hole as Hammond strapped Pits onto the penetrator and disconnected his mike cord. I took my last glimpse of Pits as Hammond swung him out of the cabin.

“Pits had a big grin on his face. He was holding his medical kit, his M-16 rifle, and an armful of splints. I said a silent prayer for him. I have a feeling the rest of the crew said a prayer for him, too. We just never talked about it.

“Down he went as Hammond snaked him down through the trees to the wounded and survivors waiting below. I’m sure they were surprised to see someone come down into their hellhole. Hammond hoisted the penetrator back up and sent a Stokes litter down to Pits.”

With Pits on the ground, the helicopters took turns extracting wounded soldiers from the jungle. Pitsenbarger was sending them up both in the litter and on the forest penetrator.

The situation on the ground was described by 1st Lt. Martin Kroah, leader of Charlie Company’s 3rd Platoon.

“I first saw Airman Pitsenbarger when he was being lowered from an Air Force helicopter sent to medevac our wounded,” Kroah said. “I observed him several more times during the course of the day. To put down on paper what that battle was like is an impossible task.

“At times the small-arms fire would be so intense it was deafening and all a person could do was get as close to the ground as possible and pray. It was on these occasions that I saw Airman Pitsenbarger moving around and pulling wounded men out of the line of fire and then bandaging their wounds. My own platoon medic, who was later killed, was totally ineffective. He was frozen with fear, unable to move.

“The firing was so intense that a fire team leader in my platoon curled up in a fetal position and sobbed uncontrollably. He had seen combat in both World War II and Korea. The psychological pressure was beyond comprehension.

“For Airman Pitsenbarger to expose himself, on three separate occasions, to this enemy fire was certainly above and beyond the call of duty of any man. It took tremendous courage to expose himself to the possibility of an almost certain death in order to save the life of someone he didn’t even know.”

Pedro 73 Hit

Between them, the two helicopters had made a total of five flights into and out of the battle area and had flown nine wounded soldiers to Binh Ba. Pedro 73 moved into the hole in the jungle canopy for the next pickup.

“Hammond spotted Pits,” Salem said. “He was signaling for a Stokes litter. Hammond hooked it up and began lowering to Pits. We could hear enemy fire down below, but Pits was ignoring it and kept motioning for us to continue lowering the Stokes litter.”

The litter had almost reached Pitsenbarger when the helicopter was raked by automatic weapons fire. It lurched as it was hit and yawed severely to the left. As engine RPM dropped, the helicopter began sinking slowly. The rotor blades were out of track, and badly so. Salem applied full right rudder to correct the yaw, but he had no control over the engine.

“My immediate concern was to keep the chopper flying and not hit any trees that were just a few feet away from the tips of the rotor blades,” Salem said. “Hammond kept the Stokes litter going down while signaling for Pits to grab hold of the Stokes litter when it came within reach so we could pull him out. I was able to keep the helicopter fairly steady now, using full right rudder. Finally, the rotor RPM began to increase and stopped our descent. Again, our main concern was to try some way to get Pits on board. He must have known that we were taking heavy ground fire.

“Hammond was now frantically motioning to Pits to get him to try and grab onto the Stokes litter, but Pits continued to give Hammond the wave-off and appeared to be hollering for us to get the hell out of there. This was his second wave-off. Without any hesitation, Pits elected to stay on the ground with the wounded.”

As Pedro 73 maneuvered up and out of the pickup hole, the litter got hopelessly snagged in the trees and had to be cut loose.

The helicopter limped to a landing at Binh Ba, but the engine could not be shut down by either normal or emergency procedures. Hammond removed some panels in the roof of the cabin and used a hammer to beat the fuel controls closed. The helicopter had taken nine hits and both sets of rotor blades were ruined.

Pedro 73 was out of commission. Bachman in the lead helicopter was told by ground control that the area was under such intensive attack that no more extractions could be attempted.

During the night, word came that Pitsenbarger and more Army casualties had been moved to an area where a landing zone would be cleared the next morning and that Army helicopters would bring them out at first light.

The report was wrong in all respects.

The VC Attack Peaks

In the late afternoon of April 11, the VC battalion intensified the attack with mortars and machine guns. Snipers in the trees shot soldiers in the back as they lay prone in the firing position.

There would be no reinforcements any time soon. Bravo Company was well off to the left flank, and the jungle was so thick that it took an hour to hack out 100 yards of single-file trail.

“I had been wounded before Pitsenbarger arrived on the scene,” said Army Sgt. Charles F. Navarro, a squad leader in Charlie Company’s 1st Platoon. “We were getting pounded so bad that I could only lie on the ground for cover. Pitsenbarger concealed my body with a dead soldier, probably to protect me from getting hit again or even from being killed if we were overrun.

“Pitsenbarger continued cutting pants legs, shirts, pulling off boots, and generally taking care of the wounded. At the same time, he amazingly proceeded to return enemy fire whenever he could. During his movement around our perimeter, he would scramble past me and deliver a handful of magazines.”

“After I was wounded, sometime around 6 p.m., Pitsenbarger came by the tree where I and several other wounded and dead soldiers [were],” said Daniel Kirby, who was an infantryman in Company C. “He looked at my wound, stated that it was not overly serious, and said something to the effect of, ‘Don’t give up; we can get out of this mess.’ He then left and that was the last time I remember seeing him.”

Navarro said that Pitsenbarger gave his handgun to one of the wounded who could not hold a rifle. Running from place to place, Pitsenbarger gathered ammunition-at least 20 magazines-from the dead and distributed it to those still shooting. Several of them had been firing their weapons on full automatic and were running short of ammunition.

“I observed Pitsenbarger communicating with the helicopter using hand signals, waving them off at least twice,” Navarro said. “At some point, the helicopter began taking heavy enemy fire. Shortly after that, I observed Pitsenbarger reaching for the Stokes litter to try and load up another wounded man. Before he reached it, the helicopter’s hydraulics were hit, causing it to go out of control. The Stokes litter tore through the jungle and fell into some trees. Later, Pitsenbarger took up a position next to me. He was killed shortly thereafter.”

Pitsenbarger died about 7:30 p.m., Navarro said.

The VC mounted three massive assaults against the perimeter that evening and Charlie Company survived the night only by calling in artillery almost on top of itself. After the artillery barrage, about 9 p.m., there was no further fire from the VC. Reinforcements, led by Bravo Company, arrived at dawn.

The PJ on the flight that went out from Bien Hoa the morning of April 12 was A1C Harry O’Beirne, who lived in the same cubicle as Pits.

“We got an urgent message to get back out to Binh Ba,” O’Beirne said. “I was the pararescueman on the first chopper. When I was put down in the jungle, I was told that there were 30-some dead and the rest were wounded. I set about helping the wounded and evacuating them on the chopper. After the chopper took off, I headed back into the jungle to help some more wounded.

“An Army captain passing, stopped me and told me that he was sorry but my buddy had been killed. He pointed in the direction of Bill’s body. I searched and found it covered with a poncho. Bill had been shot four times. I removed Bill’s gear and took the body back to the evacuating area.”

Pitsenbarger had been hit in the back, shoulder, and thigh but had kept working and fighting until the fatal round struck him in the head.

“Bill Pitsenbarger was an ordinary man,” O’Beirne said later. “He just did extraordinary things when called upon to do so. He liked country music, loved to hear Roy Acuff sing ‘The Wabash Cannonball,’ liked a beer, had a healthy interest in girls. Being brave is not the absence of fear but being able to work and do the needed thing in spite of it.”

The Medal of Honor

On Salem’s recommendation, Col. Arthur Beall, commander of the 3rd Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Group, nominated Pitsenbarger for the Medal of Honor. However, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, proposed the award of the Air Force Cross instead. The Pentagon went along with MACV.

In September 1966, Pitsenbarger’s Air Force Cross, awarded posthumously, was presented to his parents by Gen. John P. McConnell, Air Force Chief of Staff. He was the first Air Force enlisted man to be presented the second highest military award.

For more than 30 years, his memory has remained vibrantly alive. The Airmen Memorial Museum in Suitland, Md., has catalogued almost two dozen memorials, buildings, streets, and awards named for him.

His fellow PJs and others never gave up on their appeal to have his award upgraded to the Medal of Honor. The issue arose again in the early 1990s, when Piqua, Ohio, named a sports complex in Pitsenbarger’s honor.

In 1998, the Air Force Sergeants Association took up the cause. Three requirements had to be met for upgrade: (1) new information, (2) recommendation from someone in the chain of command, (3) submission by a member of Congress.

A concerted effort by the Airmen Memorial Museum, an arm of AFSA, documented the events of April 11, 1966, in great detail and gathered statements from eyewitnesses. Among those providing letters of support were seven of the surviving members of Charlie Company, including two of the four platoon leaders.

“I felt at the time, and still do, that Bill Pitsenbarger is one of the bravest men I have ever known,” wrote former lieutenant Johnny Libs.

Hal Salem, the helicopter pilot, and retired Maj. Gen. Allison C. Brooks, former commander of the Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Service, made a new nomination of Pitsenbarger for the Medal of Honor, satisfying the second requirement.

Armed with the AFSA package and the new nomination, Rep. John A. Boehner (R-Ohio) asked the Air Force, in early 1999, to upgrade the award.

In the Pentagon, the proposal had to be reviewed by various offices and organizations and might well have mired down in bureaucratic muck had it not been for a special champion. Secretary of the Air Force F. Whitten Peters, who had heard about the case from Pitsenbarger supporters, took a personal interest. He and Joe Lineberger, director of the Air Force Review Boards Agency, put their full weight behind the effort.

With the concurrence of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the recommendation became part of this year’s National Defense Authorization Act as approved by Congress and signed into law by the President on Oct. 30.

After 34 years, Pitsenbarger’s heroic actions had finally received full recognition.

On Dec. 8, 2000, the Medal of Honor was presented posthumously to A1C William H. Pitsenbarger in a ceremony at the Air Force Museum in Dayton, Ohio, not far from his hometown of Piqua. Secretary of the Air Force F. Whitten Peters presented the award, which was accepted by William F. Pitsenbarger on his son’s behalf.