Robert S. McNamara could give duplicity a bad name. In his new memoir, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam, he says that the Vietnam War was a mistake and that he knew it all along. We should have gotten out in 1963, when fewer than 100 Americans had been killed. When he and other US policymakers took us to war, they “had not truly investigated what was essentially at stake.”

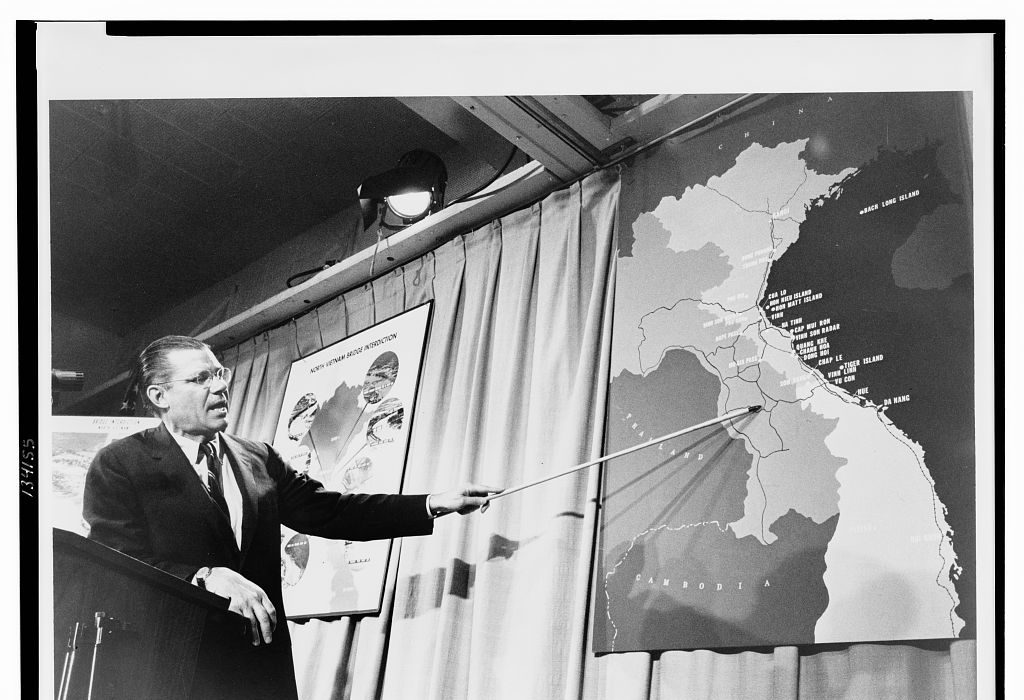

McNamara was Secretary of Defense from 1961 to 1968 in the Kennedy Administration, which led the US into the Vietnam adventure, and in the Johnson Administration, which widened the involvement to a war in which 58,000 American troops died. He was not some star-crossed functionary who went passively along with a policy he opposed. He was so fiery an advocate that Vietnam became known as “McNamara’s War.” His actions then and his statements now cannot be reconciled with honor.

The duplicity has another dimension. News accounts bill In Retrospect as a stark admission of guilt, but an actual reading of it tells a different story. McNamara does, to be sure, acknowledge that he and his colleagues were “wrong, terribly wrong,” but the admissions account for relatively little of the book’s substance. The bulk of it explains how these were honest mistakes and not altogether the fault of McNamara and his friends. They were deceived, undercut, poorly served, badly advised, and distracted by “the staggering variety and complexity of other issues we faced.”

Somehow, it is not altogether surprising that McNamara comes close to ignoring the rank and file of the US armed forces. In the entire book, there are just four brief instances, one of them in a footnote, when the troops cross his mind. The best he can bring himself to say for those killed in action is that “the unwisdom of our intervention” does not “nullify their effort and their loss.”

The people who get McNamara’s attention and regard are the anguished insiders of the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations and assorted antiwar activists, intelligentsia, and others operating on the fashionable left flank of the Democratic Party in the 1960s. McNamara was able to skip a personal crisis when the draft board reclassified his son, Craig–who, like the rest of McNamara’s family, opposed the war–from 1-A to 4-F (for ulcers). McNamara says he was “just as concerned” about those who could not or did not sit out the war at home, but his claim is not convincing. Vietnam veterans called on McNamara to donate the profits from the book to Vietnam veteran charities. He declined and will give the proceeds instead to a program to establish “dialogue” between Americans and Vietnamese.

Reaction to In Retrospect has been overwhelmingly negative, but a few voices have spoken in McNamara’s favor. President Clinton–who evaded the military draft in 1969–said that McNamara’s revelations “vindicated his view.” The Vietnamese Foreign Ministry in Hanoi agreed with McNamara that the United States had been “terribly wrong.”

McNamara never learned the real lessons of the war. In Retrospect ticks off “eleven major causes for our disaster in Vietnam,” but they run mostly to philosophical mush like “We misjudged then–as we have since–the geopolitical intentions of our adversaries” and “We failed to recognize that in international affairs, as in other aspects of life, there may be problems for which there are no immediate solutions.”

Incredibly, McNamara recalls–but regards it as insignificant–that the service chiefs told him in 1964 that the US had not defined a “militarily valid objective for Vietnam.” With similar arrogance, McNamara continues to believe that his strategic and tactical abilities were better than those of the military professionals and that his micromanagement of the war was a good idea. (Air Force operations, in particular, were so controlled that President Johnson once bragged that “they can’t even bomb an outhouse without my approval.”)

He does not seem to understand that North Vietnam was fighting a war, whereas the United States was sending signals and trying to play mind games with Hanoi. He remains oblivious to the actual lessons of Vietnam, embodied in the “Weinberger Doctrine” of 1984 by his successor, Caspar Weinberger. Before committing US forces to combat, we should ask ourselves six questions: Is a vital US interest at stake? Will we commit sufficient resources to win? Will we sustain the commitment? Are the objectives clearly defined? Is there reasonable expectation that the public and Congress will support the operation? Have we exhausted our other options? The Persian Gulf War of 1991 followed the Weinberger Doctrine to the letter, but Vietnam failed on all counts.

McNamara denies that his purpose is self-justification. In Retrospect, however, reveals him to be as stubborn as ever and working to ensure that whatever blame sticks to him or his friends is nominal. Recently, he has been a spokesman for liberal concepts and causes, and he seems to regard his Vietnam memoir as a springboard for further comment. He is irritated that people are ignoring the book’s preachy appendix on nuclear weapons.

Given McNamara’s disclosures about his judgment and character–on top of what we already knew–it is difficult to imagine that anyone wants to hear any more from him about anything. His best service now would be to go away and shut up.