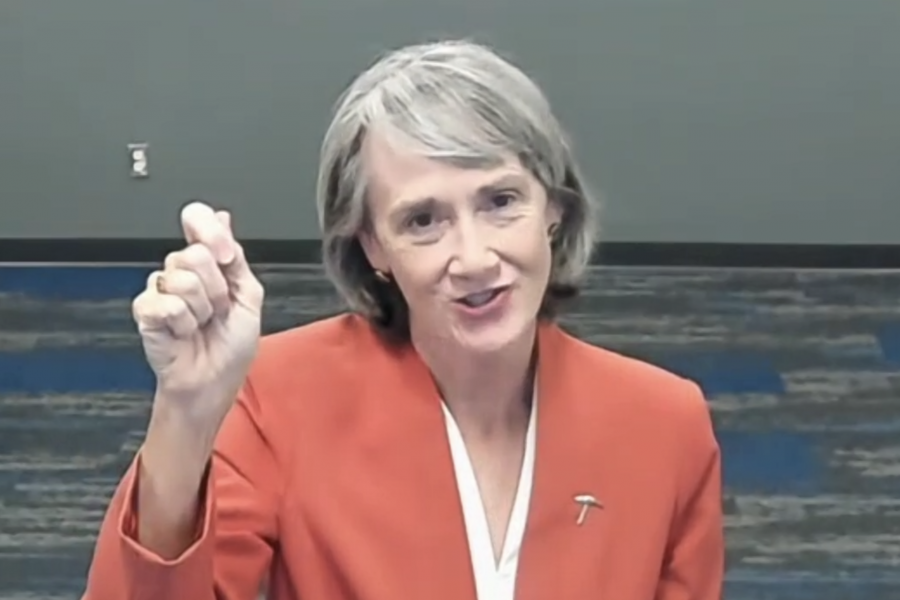

Nearly 18 months out of office, former Air Force Secretary Heather A. Wilson indicated the service has more work to do on the reforms she championed over the course of two years.

Wilson, now president of the University of Texas at El Paso, pursued multiple pet projects in the top civilian post. Three of those initiatives can go further, she said Oct. 22 during a conference hosted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The former Secretary was known as an advocate for improving the military science and technology enterprise. She launched the “Science and Technology 2030” effort in September 2017 to speed the pursuit of tools like artificial intelligence and hypersonic weapons, and to boost the Air Force’s ties to academia, small businesses, and other underutilized parts of the research world. That project produced a new strategy in April 2019 that the Air Force Research Laboratory is trying to make real.

“I worry that there are still not enough scientifically and technically literate people at the senior levels in the service to understand what an enabler that is,” Wilson said.

Acquisition reform, a perennial concern for the Defense Department, also requires more scrutiny. Wilson advocated for a greater focus on software, and endorsed the “try before you buy” approach that is starkly different than traditional military procurement. She began releasing annual acquisition reports that the Air Force has not continued after her tenure.

In trying to speed the process of buying combat assets, Wilson wanted to give defense contractors more leeway in designing systems instead of levying prescriptive requirements.

“It’s the requirements system that really needs reform, and nobody ever thinks about that part,” Wilson said.

That effort is connected to the service’s attempt to make daily Pentagon bureaucracy less burdensome for Airmen. Wilson and staff rescinded 340 regulations and rewrote others that Airmen felt only made their lives harder, like one specifying how to build an obstacle course. A copy of each trashed regulation ended up in a pile next to her door.

“If Grand Forks Air Force Base needs an obstacle course, I bet they can figure it out. They don’t need to be told how to do everything,” Wilson said. “Particularly in the warfare of the 21st century, communications are going to be degraded. We’re going to have to depend on people making decisions using command intent to accomplish the mission. … We needed to treat people that way in peacetime.”

She indicated that similar concerns around military permissions will play out as the Pentagon and intelligence community’s space operations mature.

“Until recently, you needed the permission of the President of the United States to come close to another satellite. But given the right guidance, an 18-year-old can kill someone on his own authority in the middle of a war zone,” Wilson said. “Those are interesting, centralized controls for some things, and very decentralized in other circumstances. Getting that balance right will be difficult.”

One major initiative that Wilson worked on has gotten across the finish line since she left: a new promotion system. The Air Force is now judging people for promotion based on performance in their career field, and comparing them to others in similar professions. Until recently, the service lumped employees together regardless of career, which favored pilots with combat experience but led to underrepresentation in leadership of scientists and engineers.

“[Then-Chief of Staff Gen. David L. Goldfein] made a personal commitment to me that he would keep stewarding this, and in the end, it was signed and done,” Wilson said. “Of all the things we changed in the service for the long term, that’s probably the one that’s going to have the most important impact. … We weren’t stewarding the whole pipeline well. That’ll make a huge difference.”

In her new job, she continues to push for improved access to education, modernization of the nuclear triad, and a military force that can connect any shooter to any sensor to move faster in combat.

“Today in America, about 62 percent of boys and 69 percent of girls go on from high school to some form of college or technical training or community college,” Wilson said. “If we are going to maintain our preeminence and leadership in the world, we have to commit to educating more of the next generation in meaningful ways. … It is a national security issue.”