The Department of the Air Force’s Advanced Manufacturing Olympics showcase kicked off this week with a look at where military sustainment has come so far and what more it has to accomplish.

Air Force acquisition boss Will Roper is pushing the service to adopt three-dimensional printing and other forms of advanced and additive manufacturing that are more prevalent in commercial industry to cut down on sustainment costs, which make up 70 percent of the USAF budget.

“We want to make parts that we currently can’t supply easily,” Roper said. “We want to reverse-engineer parts that we may not have the designs for anymore. We want to look at repeatability of parts so that we’re not critically coupled to an individual printing machine. And we want to look at the entire process of what it takes to get a novelty manufactured part onto a critical mission airplane or satellite.”

The Air Force Rapid Sustainment Office’s Advanced Manufacturing Olympics began over the summer, with multiple challenges where 64 teams can win up to $100,000 in prize money.

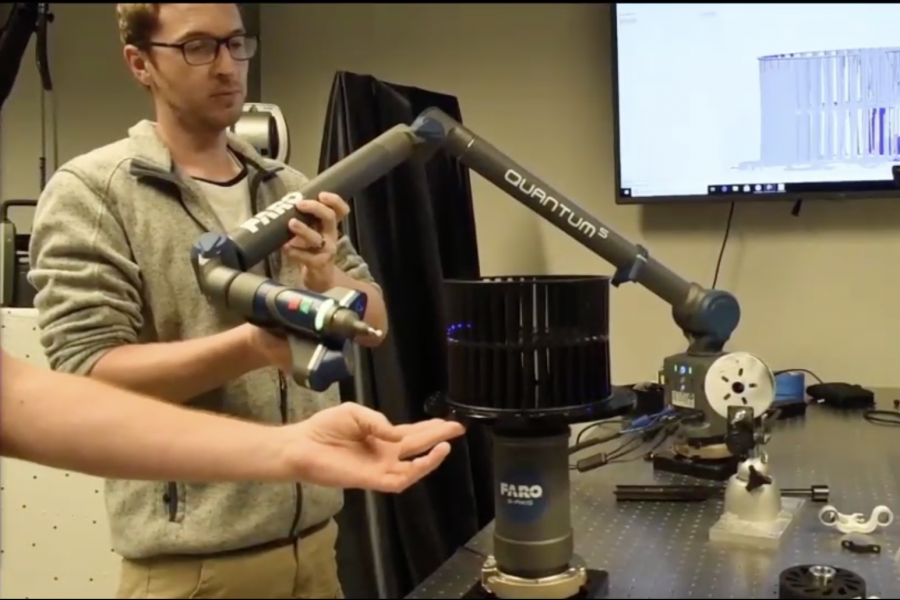

Air Force Magazine previously reported that teams in one event are trying to replicate as many parts as possible from a box of components using reverse engineering and modeling. Another set of teams was tasked with fabricating flight-ready F-16 fighter jet parts and getting them certified for flight. A third challenge looks to prove that teams can produce new building materials that work as well as traditional metals and polymers. The fourth focuses on supply chain challenges, and the fifth aims to accurately build a 3D-printed part from existing design data.

Air Force Secretary Barbara M. Barrett added that participants will “directly influence” a new roadmap that is in the works this year to spread those techniques across the Air Force and Space Force.

To make meaningful progress in sustainment, the military needs to get spare parts in a matter of hours or days instead of weeks or months. It also needs to improve the accuracy of modern manufacturing techniques, and to ensure that components will be ready to fly no matter how or on which 3D printer they are made.

The Air Force has printed nearly 10,000 total parts (not just as part of the Olympics), many of which are installed on aircraft, Roper said. Barrett pointed to 118 phenolic wedges—“a small but critical piece between the center wing box and the inner wing splice”—on each C-5M Super Galaxy airlift that needed to be replaced due to moisture and age.

The service turned to 3D printing to build more than 6,000 of those wedges 88 percent faster, 35 percent lighter, and nearly $1 million cheaper than sourcing them from a defense contractor, Barrett said.

Officials in the Air Force’s maintenance depots are looking to grow their projects in the new fiscal year, including getting a head start on manufacturing components for the B-21 bomber that is still in development by Northrop Grumman.

Jason McCurry, the Reverse Engineer and Critical Tooling engineering branch chief at the Oklahoma City Air Logistics Complex, Okla., said his group is analyzing the design of dozens of B-1 bomber parts to build new blueprints and create those components from scratch.

“That started off with just eight different part numbers,” he said. “It’s now up to 76 different panels that we’ve reverse-engineered for the entire interior for the B-1s.”

That effort started about two years ago, and REACT is getting ready to start producing 3D-printed interior panels over the next five years. The team is reaching out to the B-2 and B-21 bomber programs to see how they can assist on those as well.

Damon Brown, who runs the Reverse Engineering, Avionics Redesign, and Manufacturing team at the Warner Robins Air Logistic Complex, Ga., noted his group is working on a munitions loader that hasn’t been updated since it was fielded in the early 1980s.

“We redesigned a circuit card … that should increase the reliability by about 75 percent,” he said. “One of our other systems is a weapons control unit for a platform. We completely redesigned it. The circuit cards built into it were out of stock. … Now we’re manufacturing those spares and so now we’ll be able to keep that platform flying for many more years.”

He did not say which aircraft that second project focuses on.

Brown argues the Pentagon needs to possess more of the technical data for parts up front so maintainers can know more about the components that make up combat assets. That would make the sustainment process more efficient and lessen the Air Force’s reliance on contractors when it needs a new order or an upgrade.

He believes the Air Force’s “digital campaign” can overhaul how it does acquisition for the better. Right now, the service has to turn 3D, computer-assisted drawings into two-dimensional blueprints to store in a system that can’t handle something more advanced. That flat design is what gets emailed around while the hardware is built, which limits how much testing and tweaking can be done on computers in the meantime.

“The design, the contracting, the communication all about these systems would all be digital. … [Under a more tech-savvy model,] it’s not cost-prohibitive to acquire that extra data because it was designed digitally in the first place,” Brown said. “I hate to say that it would put my shop out of business, but it would make for a more sustainable Air Force.”