Federally funded computer engineers at the Aerospace Corporation are developing simulation software that will let U.S. space agencies virtually game out the consequences for satellite constellations of everything from software upgrades to military confrontations.

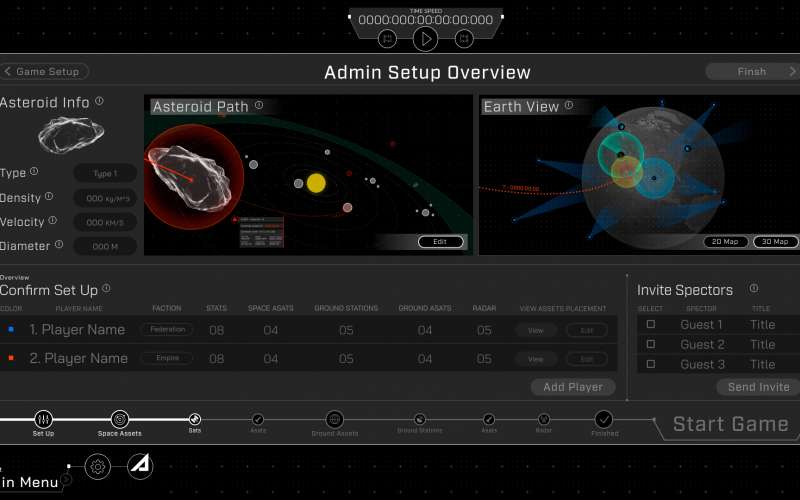

Prairie, as the software platform is dubbed, marries the latest techniques in digital twinning with recent advances in social media and gaming platforms, to create a cloud-based virtual space environment controlled through slick, intuitive user interfaces, Randy Villahermosa, general manager of Aerospace’s iLab, told Air Force Magazine.

“The aim is to put the user in control,” he said. “The only real constraints [on in-game activities] are physics-driven … We wanted to give the user the ability to customize the scenario,” he said.

The program is designed to make the game simulation as realistic as possible. “In space, operators have to make decisions in a split second,” said Joshua Cohen, engineering manager at iLab and the leader of the Prairie team. Using existing commercial game engines like Unreal and Unity, his team created “a Star Trek-type interface” for Prairie, so actions can be taken “with one or two clicks [of a mouse] or touches of a finger,” Cohen explained.

He added that the platform is built to be continually updated, so it can keep up with constant disruptions in the space sector caused by the emergence of new technologies. “We wanted to make it open ended, … a system that could incorporate innovations as they came online,” he said.

The architecting process currently in use by the Department of Defense and other federal agencies is too slow, Villahermosa said. “Much of it is done the same way it was done in the days of the Apollo program,” he added. Speed will be the key to prevailing in the new space era, he said.

“Younger people are very comfortable with the gaming interfaces,” observed Villahermosa. But what distinguishes Prairie is the engineering that’s behind it. “Users will be able to create effects and use analytical tools to determine impacts,” to simulate the use of anti-satellite weapons and other kinetic interventions, he said.

But Prairie is much more than a wargame—it can be used to test real satellites.

“We’re very excited by the possibilities of digital twinning”—the creation of extremely detailed software models of real pieces of engineering like jet engines or satellites, Villahermosa explained. In the virtual Prairie environment, satellites are individually programmed avatars with a very high level of fidelity to the actual spacecraft.

This fidelity makes it possible to use Prairie to test upgrades to the latest generation of software-defined satellites. So detailed are the digital twins in Prairie that the operators of these constellations will be able to load software upgrades and other programming changes in the simulation—to check they work safely and correctly before deploying them on the real spacecraft.

But it’s a model called “mixed reality gaming,” that really lets Prairie’s developers “take it to the next level,” Villahermosa said. It will be possible to “hook up test hardware on a workbench … and use that to run the software” loaded into the simulation, to provide an extra layer of fidelity.

In an unforgiving environment like space, these test deployments of software speedily written using the latest agile development processes are essential, Villahermosa said.

Prairie will also provide a way to test and model the use of artificial intelligence in space. The platform will enable “virtual fly-offs,” where two satellites will complete the same maneuver, one powered by AI and one controlled in traditional fashion by a human operator, he said.

“We need to find out where AI works better than human operators,” said Villahermosa. “We need a very tangible understanding of where it might be useful to employ AI.”

AI can also be used to re-run games played between human opponents over and over—changing one factor, one decision, each time—“to discover which moves lead to success and which don’t.”

Users concerned about putting their proprietary or even classified technology into the Prairie cloud will have options to preserve their intellectual property, Villahermosa said. Prairie will be able to exchange data with a digital simulation safely confined to the user’s own network through an application programing interface. Users will also be able to run their own version of Prairie in their own cloud, if desired.

“We took a page from the playbook of commercial gaming,” added Cohen. “Code it all once, and make it deployable on any platform.”

Aerospace Corporation hasn’t decided what business model it will adopt for Prairie or whether or how to charge for its use, Villahermosa said. But users will be restricted to the “U.S government spacefaring enterprise” of military and civilian agencies. “We want our partners in that enterprise, their engineers, to be able to contribute.”

He added that a small team of engineers had been working on the project for two years. “We hope to have it ready to demonstrate in November,” he said.