A Senate Armed Services Committee hearing brought an interagency dispute over the future of spectrum management further into public view on May 6.

SASC and the Defense Department are sparring with the Federal Communications Commission over its April approval of a Ligado Networks plan to build ground terminals for a broadband Internet network in the electromagnetic spectrum’s L-band, near the part of the spectrum occupied by GPS signals. Ligado says its signals will be low-power enough and far enough away from GPS that navigation wouldn’t be disrupted, while multiple federal agencies say Ligado’s systems would vastly overpower the faint GPS signal.

Prominent lawmakers and an array of federal agencies, including the Defense, Commerce, and Transportation Departments, want the FCC to take back its ruling. For the FCC to reverse its decision, the Pentagon needs to go through a formal petition process with the National Telecommunications and Information Administration to prompt the FCC to reconsider. DOD Chief Information Officer Dana Deasy said he is talking to the NTIA, and DOD has until the end of the month to lodge its objection.

“There is a very formal process that the FCC goes through. It’s a very good process and they’ve used it for years,” Deasy said. “In this particular case, we did not see that process being followed. … We think this is the first time ever where the FCC has taken an arbitrary and independent decision where it was … unambiguously opposed by multiple federal agencies.”

The FCC released a statement arguing it is “preposterous” that the Pentagon was blindsided by its vote and noted its support from the State and Justice Departments.

“Nothing said today changes the basic facts that the metric used by the Department of Defense to measure harmful interference does not, in fact, measure harmful interference, and that the testing on which they are relying took place at dramatically higher power levels than the FCC approved,” the commission said.

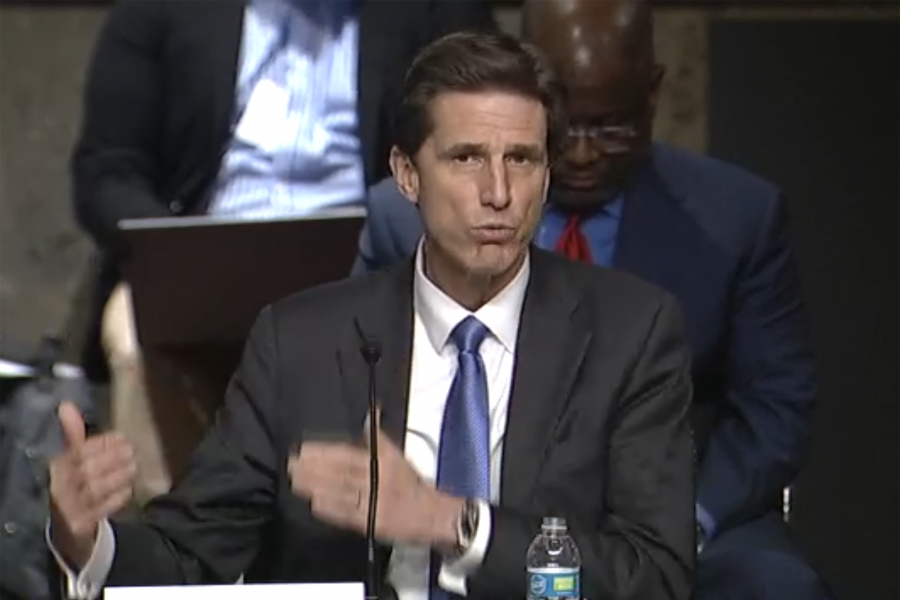

Deasy, Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering Mike Griffin, National Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing Advisory Board Chairman Thad Allen, and Chief of Space Operations Gen. Jay Raymond testified at the hearing. While multiple senators questioned why the FCC and Ligado weren’t represented, a committee spokesperson said those officials are not national security experts and would fall under the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee’s jurisdiction.

Two prominent issues in the yearslong fight came forward during the hearing: the parties argue that research underpinning the other’s argument is invalid, and stakeholders believe there has been a breakdown in the consensus-building process used by the FCC.

The FCC approved Ligado’s proposal with conditions attached to lower the risk of interference. The company must leave 23 megahertz of space between its own part of the spectrum and the area used by neighboring operations, and lower its base station power levels by 99.3 percent to 9.8 decibel watts.

“The order also requires Ligado to protect adjacent band incumbents by reporting its base station locations and technical operating parameters to potentially affected government and industry stakeholders prior to commencing operations, continuously monitoring the transmit power of its base station sites, and complying with procedures and actions for responding to credible reports of interference, including rapid shutdown of operations where warranted,” the FCC wrote April 20.

Military officials contend that the FCC’s expectations are unreasonable and would drive “unprecedented accelerated test, modification, and integration of new GPS receivers on existing platforms” to protect the enterprise and “significantly degrade national security.

Ligado’s proposal has changed over the years, but Deasy argues that the Pentagon’s 2018 tests that proved harmful interference still stand. He is not aware of any specific testing that occurred since the April 20 vote to account for the FCC’s guardrails. The company alleges DOD is working with outdated information.

Multiple lawmakers appeared skeptical of DOD’s argument and asked why the FCC would issue an unusual, unanimous vote if it felt products that rely on GPS, from military jets to commercial airliners to athletic watches and ATM machines, would be threatened. Some see the squabble as a breakdown in federal communication that needs to be resolved.

“This process has exposed a fault line in spectrum decision-making,” FCC Commissioners Jessica Rosenworcel and Geoffrey Starks wrote in a joint statement. “As we move to the next generation of wireless service, it is imperative that we have an improved interagency system and a stronger whole-of-government approach to our 5G effort.”

Lawmakers may include language in the fiscal 2021 defense policy bill to protect the GPS enterprise, but defense officials stopped short of calling for specific legislative action. Commerce Committee members could take up their own bill text to review the FCC’s approval process.

SASC Ranking Member Sen. Jack Reed (D-R.I.) worried that intergovernmental discussions are failing and the FCC could start making unilateral decisions based on its own intuition. Allen, the retired Coast Guard commandant, responded that the commission’s regulatory process should be reviewed because the scope of its portfolio has grown from radio broadcasts in the early 20th century to modern issues like broadband communications.

“No practical solution or mitigation is available that would permit Ligado to operate without high likelihood of widespread interference,” the panelists told the committee in prepared remarks. “The bottom line is that there are too many unknowns and the risks are too great to allow the proposed Ligado system to proceed in light of the operational impact to GPS.”