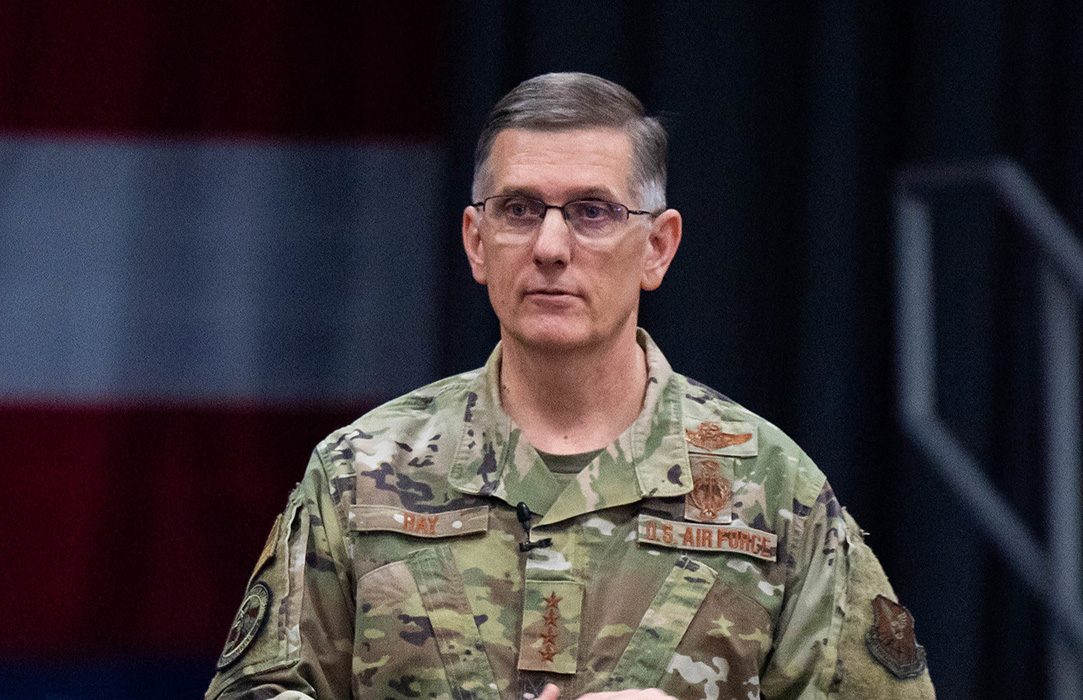

An exclusive interview with Gen. Timothy Ray, commander of Global Strike Command and the Air Force Strategic component commander for STRATCOM.

Gen. Timothy Ray is the commander of Air Force Global Strike Command and the Air Forces Strategic component commander for USSTRATCOM. He directs the Air Force’s three bomber fleets, its land-based Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) force, and the nuclear command, control, and communications enterprise. He spoke exclusively to Air Force Magazine Editorial Director John A. Tirpak on March 31 about the evolving bomber force, AFGSC end strength, the changing nature of deterrence, and future weapons. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. You’ve said the Air Force will need more than 100 new B-21 bombers. Is the final number coming more into focus?

A. I’m very comfortable with where the B-21 program is, writ large, and we’ve said publicly that we think we need 220 bombers overall—75 B-52s and the rest B-21s, longterm.

The size of the bomber force is driven by the conventional requirement, and then we manage the nuclear piece inside of that, based on treaty and policy. In the context of the National Defense Strategy (NDS) and great power competition, 220 is where we think we need to go.

Those 75 modernized B-52s, … that’s not a simple set of modifications, but we think we have a plan going forward. It will feature a bridging mechanism to keep the B-1 fleet viable and—where needed—modernized, to get us through that gap. It features keeping the B-2 viable until we know we’ve got enough penetrating capability with the B-21.

There’s a lot of things that have to happen between now and, I would say, five years from now, to begin setting a path beyond 175. I won’t call it aspirational; I think it’s a realistic assessment of what we think we need to do. I don’t think that even my replacement will make a decision on that. I think it’s two commanders from now who will really determine the exact path on the bomber roadmap to take us past 175.

Q. The Air Force has asked to take some B-1s out of service to help pay for Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2). Can you fulfill the NDS with what’s left?

A. If we right-size the B-1 fleet, based on what I think we can sustain, and if we make some structural and capability modifications. … My goal would be to bring on at least a squadron’s worth of airplanes modified with external pylons, to carry the [Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon, or ARRW] hypersonic cruise missile.

Some B-1s need significant structural work, so if we limit that liability, then we can do smart things, and we’ve got support from Congress to do this.

All aspects of long-range precision strike absolutely depend on a viable Space Force. That has to happen. Anyone who wants to do long-range precision strike in the future, they can’t be serious about it unless they’re fully partnered on all-domain command and control and the Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS).

Q. Did you request money for hypersonic weapon pylons in the 2021 budget?

A. No, that’s not in the current budget, that’s a project we’re working on. There are several versions that we could contemplate, but we believe the easiest, fastest, and probably most effective in the short-term will be to go with the external pylons. And as we move toward the ARRW, that is a good weapon/airframe and configuration match to get us quickly into that game.

Q. Would you commit to the ARRW?

A. I think we’re going to commit to the ARRW, because I think our carriage capability is good for that. With some mods, we may be able to increase the B-52 carriage but, really, the ability for the B-1 to take up hypersonic testing takes a load off the B-52 for the engines, the radar … and there’s a good number of communications upgrades I need to make.

We actually have a very aggressive game plan, here, over the next three to five years. We’ll have to commit more aircraft and maintainers and operators to test. Typically, we have two bombers at Edwards [Air Force Base, Calif.]; we’re going to ramp up to eight.

Q. Do you think you’ll need a conventional version of the Long-Range Standoff weapon (LRSO), along the lines of the Conventional Air-Launched Cruise Missile (CALCM)?

A. First things first. The ALCM is aging out on us. I pulled alert in the old days of [Strategic Air Command] SAC with ALCM, and I’ve shot CALCMs in anger. The utility of those is unquestionable. We’ve got to replace the ALCM.

Realize that everything we do will be driven inside of a treaty context. I’m pleased with the thinking and approach in the LRSO program; I think that’s going to be a very good missile. If we needed a conventional cruise missile in a hurry, with even longer range than the [Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff, Extended Range], I would start there, with the LRSO.

I’m not asking for it, because I’ve got to solve the nuclear version first. But as opportunities present themselves down the road, LRSO certainly has some attractive features and capabilities for a conventional cruise missile.

Q. When you talk to Congress about strategic modernization, do you get the sense that everybody’s on board? What do the unconvinced need to hear?

A. I think the awesome part of democracy is that we debate the issue. It’s always healthy to question what you’re doing to make sure you’re doing the right thing.

The context in which we view the nuclear triad is important, and we can’t pick the context. It has to be viewed in the context of the now-existing Chinese triad, and a fully modernized and augmented Russian triad. And absolutely, in the minds of our partners and allies, to whom we’ve promised protection—so they don’t have to go down the path of a nuclear program.

That’s the very clear reality of where we are. And when you explain things that way, it becomes an easier way to understand the problem.

We have had significant reductions in the number of nuclear weapons in the past, and we’ve done it through treaty. My advice and counsel was, ‘you’re going to have to continue down the path until you’ve got a change in the world, and it has to be done in a multilateral fashion’.

Q. Russia has heavily modernized its strategic weapons. Has that fundamentally changed deterrence?

A. The biggest change is the number of players on the field, and our ability to manage multiple problems at one time.

I think the triad concept remains very firmly intact. The number of ICBMs creates very significant challenges for anybody who would attack us, they would need to use a very high number of weapons. … Our ability to strike back keeps the bar very high. The [Sea-Launched Ballistic Missile submarine] fleet is very survivable, and certainly has the visibly flexible deterrent of a bomber and its ability to go in multiple places and shoot from multiple axes.

We’re going to have to continue to think about the command and control viability, and how we keep space very clearly in the middle of all these conversations. But I don’t see that, broadly, deterrence has changed.

Q. You’ll need an aggressive schedule of convoys when you replace Minuteman with the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD). Will you have enough manpower, and the new helicopter in hand, in time to do that?

A. I believe so. We’ve done this before with Minuteman and Peacekeeper, so it’s not a new thing. But when we designed the GBSD, it is a single weapon system, now, and not simply the silo and the launch-control facility. It’s an integrated capability. And we think that will give us a far more secure, far more reliable, and easy-to-upgrade system.

Right now, we think there will be a two-thirds reduction in the number of convoys and the amount of times we have to open the silos. We’re working with the local communities and states on some of that thinking.

Q. The bomber roadmap of a couple of years ago said AFGSC would have to live within a certain end strength, and it couldn’t add systems without getting rid of some. The “Air Force We Need” analysis, though, called for more bomber squadrons. Will your manpower go up, or down?

A. When the B-21, GBSD, new helicopter, and new cruise missile are all bedded down, the goal for the command is to actually have fewer people. For example, you go from a four-person B-1 crew to a B-21 with a two-person crew, right? With GBSD, there will also be fewer people involved.

Broadly, we can’t just keep throwing manpower at these things, we have to be really smart about that. Our goal is a net reduction in manpower. I think that’s the right thing to do for the taxpayer and for the force.

Q. So, after a few years, you would expect to start reducing manpower?

A. You’ll probably have to grow a little bit before getting smaller. You’re going to go from three [to] four bomber fleets to get to two. You have to work through weapons generation facilities, training pipelines, etc. We know where we want to be, roughly, and we know where we are, and it will be a very interesting path to work through the next three to five years to get certainty on that.

Q. The Army’s new Long-Range Precision Fires program is aimed at a lot of the target sets that have traditionally been the purview of the Air Force. Is a roles and missions debate brewing?

A. I don’t believe a roles and missions conversation is really the smart path forward. I believe we all recognize and acknowledge the need for long-range precision strike. Again, I underscore, ABMS and JADC2 are the entering argument, and why we’re leading that effort for the joint force and why the SecDef and the Chairman [of the Joint Chiefs of Staff] look to us to do that.

I believe that [the Army is] not really looking to shoot at ranges fundamentally different than what we could with the [hypersonic] weapon, but we add several thousand miles to the launch point. So, I wouldn’t get into, there has to be the right this-and-that. None of it matters unless we get JADC2 and ABMS and space right.

What we bring differently from them is, I can shoot from anywhere on the planet. A ground force will have limitations. I wouldn’t say that’s not necessary, but they don’t have the universal access that we will from the air side. So, I think there’s a clear advantage to having that in the arsenal, but to choose between that or the long-range strike, I don’t think is the right informed debate.

Q. Is it settled that the arsenal plane will be the B-52? Or is the aperture open to looking at other kinds of platforms?

A. The aperture is still open to looking at better ideas—and more ideas.

I believe we should really press into that. You like to have multiple ways to get to the right long-range strike volume. And if you can find a more affordable path, then we should look at that.

The way we do acquisition, we usually buy a platform and keep it for a long period of time. I think there’s value to the Century Series approach, where we buy an aircraft, we pay for the design, but we don’t pay to sustain it for 30 to 40 years. We pay to keep it for a little while because technology is moving so quickly.

Q. How do you think that concept will work in AFGSC?

A. I think we’re going to continue to ask industry, can you do something where I only buy a small number, and I only fly it for 10 years? But I’ve got to have the conversation about price point and where that return on investment is. So, there’s a lot of work to be done. We haven’t really tasked industry to put all their creative energy into this just yet. I think we need to press harder on that.

Q. Is there a role in AFGSC for attritable-type systems?

A. Absolutely. Our goal is to be the world’s most feared and respected long-range force. Those kinds of capabilities can be added to our arsenal. Our ability to carry a lot, a long way, and reach out is one of the more important attributes in this next era of conflict.

With everything we’re acquiring, we’re looking for margin and affordability. The attributes we want are modern and mature technology; to own the technical baseline so that we can affordably and competitively modernize; [and] modular and open systems, so we can rapidly upgrade and update.

We’ve kept requirements very stable, and our intent is to get things on the ramp or in the silo on time and then run a modernization program. So if you continue down that path, you could do lots of things that I think are important.