Boeing 767-2C freighters, minus specialized military equipment, wait to be converted to KC-46 tankers at the Boeing plant in Everett, Washington. Photo: John Tirpak/Staff

KEEPING THE PEGASUS SOLD

Everett, Wash.—The Air Force was supposed to have started receiving its first tranche of 18 operationally capable Boeing KC-46 Pegasus tankers by now. Boeing acknowledges they’re late, but insists the principal holdups are government-required paperwork and agreement on contract terms. The company says the airplanes will be in USAF’s hands by the end of this year.

The Air Force is less confident, and says it expects the aircraft to show up for duty in the spring or summer of 2019.

The contractual deadline is October.

Boeing launched a full-court press in May to shore up support for the tanker, trying to reassure the public and congressional leaders the program is on solid footing.

In late April, a letter signed by 50 members of the House was sent to the heads and ranking members of the Armed Services and Appropriations committees acclaiming the virtues of the KC-46 and the Air Force’s sharp need for the airplane, urging the chairmen to “support the procurement of 18 tankers” in the Fiscal Year 2019 defense bills.

_Read this story in our digital issue:

Days later, Boeing flew 22 defense and aerospace journalists to the company’s Everett, Wash., facilities to see the KC-46 manufacturing effort and answer questions about the state of the program. (Air Force Magazine accepted travel and accommodations from Boeing to attend).

Major substructures and systems of the KC-46 are built in Wichita, Kan.; the KC-46’s first base will be McConnell AFB, Kan.

Tinker AFB, Okla., will be the KC-46 depot, while Altus AFB, Okla., will be the tanker’s second base. Final assembly takes place in Everett. Many of the signatories of the House letter hail from districts in those three states.

What reporters saw in Everett and at Boeing Field, about 30 miles away, was a fleet of 34 KC-46s in various stages of production, ranging from empty “green” fuselage shells to nearly complete gray-camouflaged aircraft. The bulk of the airplanes were in the form of 767-2C freighters; largely completed airplanes with all the necessary wiring and strengthening, but still waiting on all the specialized military equipment needed to make them into tanker/transports. That equipment comprises refueling booms and hoses, as well as other fuel transfer equipment, military radios, avionics, self-defense systems, electromagnetic hardening, specialized lighting, extra fuel tanks, and additional plumbing necessary to make it all work.

Boeing officials said their “goal” is to whittle down to 30 days the conversion time to make a 767-2C into a KC-46, but the company has not yet done so. Boeing’s final conversion building can handle four tankers at once.

The 767-2C and KC-46 completed tasks necessary to receive final Amended and Supplemental Type Certifications from the FAA in April. Since the KC-46 is derived from a commercial aircraft, it must meet FAA standards before meeting military standards.

Reporters also saw an even busier effort next door, where dozens of 737s of several different versions and Navy P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol craft—derivatives of the 737—are in production. Boeing is producing more than 35 737s a month, and Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson said in March congressional testimony she thinks the company puts precedence on its commercial line; what she called one of USAF’s “frustrations” on the program.

Leanne Caret, CEO of Boeing defense, told reporters the KC-46 is Boeing’s “top priority.”

A painted and converted Air Force KC-46 tanker at the Everett plant. Photo: John Tirpak/Staff

Boeing acknowledged from the beginning of the KC-46 program it had underbid on price in order to win the contract. It said at the time the volume the tanker would add to the company’s production lines, along with prospects for future USAF and foreign tanker sales, would make it worth the company’s while to absorb some of the development cost, contractually capped at $4.9 billion. The fixed-price contract made Boeing responsible for any overages beyond that figure.

As of its first quarter 2018 report, Boeing has taken more than $3 billion in pretax charges on the tanker program. Those overages have “continually decreased over time,” as technical problems have been ironed out, Caret said in an Everett press conference. She noted the KC-46 remains in development, but pledged the company would “do the right thing” to deliver an aircraft that meets the Air Force’s “intent.”

Noting the large number of conversion-ready fuselages at the Everett plant, Caret said production will soon “start really ramping up.” She chalked up the current delay to “working through flow times,” and various DOD and FAA inspections and paperwork. She said the government and Boeing are working together as a collaborative team to get those first 18 aircraft delivered. That milestone is called Required Assets Available, or RAA, which is necessary to declare operational capability with the KC-46.

The KC-46 contract calls for 179 airplanes to be delivered through about 2028. The Air Force expects to field 15 of the new tankers every year until then.

KC-46s under construction at the facility in Washington. Photo: John Tirpak/Staff

FIXING DEFICIENCIES

The Air Force in May was refusing to take deliveries of any KC-46s because of two problems, which Boeing officials maintained require a software fix only—not hardware—and that other problems that have made headlines in recent months are either well understood or aren’t covered in the contract. However, they promise to work with USAF to fix them.

The two problems involve the boom operator’s imaging system and a series of uncommanded disconnects when the tanker is deploying the probe-and-drogue-style hose refueling system.

The Remote Vision System allows the boom operator, who sits behind the cockpit in the KC-46, to see what’s happening at the back of the plane, wingtip-to-wingtip. It generates an image, which allows the boomer—wearing special glasses—to see the situation in 3-D on a series of screens. It’s focused to a point about 30 feet behind the airplane. This image can be seen in ambient light or, if blackout conditions are required for the mission, in infrared, with the Long-Wave Infrared (LWIR) system.

In “very low sun-angle situations,” the aircraft can throw a shadow on the boom operation, which obscures the point of contact, said Sean Martin, company air refueling test operator. Also, sunlight can reflect off the receiving aircraft into the camera, obscuring the view for the boomer. Both problems can be fixed by “tweaking” software, he said. As part of that effort, Boeing will also change the controls on the boom operator’s system to make it “more intuitive” to users, each of whom seem to prefer slightly different settings of the lighting, Martin reported.

The second issue involves the KC-46’s hose-type refueling system, used by the Navy, Marine Corps, and many allied air force jets. If the hose bends too much, too close to the tanker, or there’s a pull on the hose exceeding 620 pounds, the hose automatically disconnects from the receiver aircraft. Again, Martin said, software changes will correct the situation.

Another problem that has been in the news is that there have been contacts between the KC-46’s boom and receiving aircraft outside of the protected area surrounding the receiver’s fuel receptacle, scraping the skin of the receiving aircraft. The Air Force has expressed concern that if this happens with a stealth jet, its low-observable coatings could be compromised, potentially forcing a mission cancellation. The KC-46 has no way to detect such contacts, although no refueling tests have been done with stealth aircraft to date.

Caret said the scraping issue is “not new,” and has happened before with the KC-135 and KC-10. However, there was no requirement written into the contract that the KC-46 have a means to detect such contacts. Boeing is working with the Air Force to address the potential problem, she asserted.

ACC is preparing a Fighter Roadmap to answer questions as it shifts increasingly to a fifth generation fleet. Photo: SSgt. Andrew Lee

THEY’RE TOUGH TO FOLD

As the Air Force gets ready to build its Fiscal 2020 Program Objective Memoranda, or POM—the five-year plan that will govern the service’s spending through 2025—service and industry leaders have acknowledged that a number of program- or portfolio-specific “roadmaps” are being built to inform that plan.

Air Combat Command chief Gen. James M. Holmes told Air Force Magazine in late April a “Fighter Roadmap” is being developed to answer many of the challenging questions facing ACC as it tries to shift from a largely fourth generation fleet to a fifth generation fleet.

“We’d like to lay it out in front of the [Pentagon] leadership this fall as we work through the details of the ’20 POM,” Holmes said in an interview, “and get agreement on it there, so we can take it to the Hill.”

With Congress, he said, ACC will “socialize” the document with interested members who may have concerns about specific programs, fleet sizes, or basing. Holmes said this would be similar to what Air Force Global Strike Command boss Gen. Robin Rand did “with his Bomber Roadmap” in the summer of 2017.

Despite what many thought would be a radioactive agenda for retiring the B-1 and B-2 bombers within the next 15 years or so, Global Strike Command’s Bomber Vector has run into little opposition on Capitol Hill. Rand assured members of Congress—as did Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson in April—that any base now fielding B-1s or B-2s will not close, but simply swap them for new B-21 bombers, which will become available starting in the mid-2020s.

The service made that official in early May, announcing that Dyess AFB, Texas; Ellsworth AFB, S.D.; and Whiteman AFB, Mo.; are the reasonable alternatives to receive the B-21 when it comes online. (Barksdale AFB, La., and Minot AFB, N.D., will continue to fly the B-52, which will remain in service through 2050.)

Holmes said the fighter roadmap will explain what new air dominance platforms USAF needs, how fourth and fifth generation fighters will communicate with each other, what new air-to-air and air-to-ground weapons are required, and how systems like the F-15, F-16, and A-10 will gradually be phased out as F-35s comprise a larger proportion of ACC’s inventory, among other details.

The ACC plan will also chart the way forward for USAF to build up from 55 fighter squadrons today to about 70 squadrons circa 2025, as the service believes this is the required force to meet the new National Defense Strategy. The roadmap will detail “the logic and the math” underlying that requirement, Holmes said.

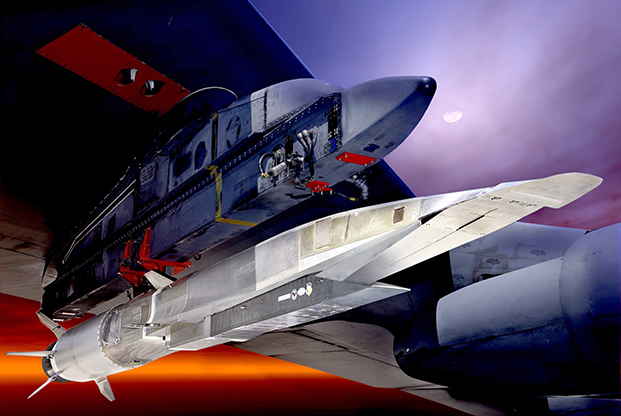

The X-51A Waverider, shown here tucked under the wing of a B-52, will demonstrate hypersonic flight. Photo: USAF

Deputy Defense Secretary Patrick M. Shanahan revealed to reporters in April that the Pentagon’s new Undersecretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, Michael D. Griffin, is building a hypersonics roadmap, also to be developed in time for the 2020 POM, and which will probably be complete this summer.

“Overlap of the technical challenges is pretty high,” Shanahan told reporters in Washington about the various approaches and potential systems applying hypersonics technology. Because all the services—and many entities such as DARPA—are pursuing hypersonics research, Griffin will be looking for common building blocks to feed all the research efforts. Where the projects should differ, Shanahan said, is mainly in whether the systems being developed are “ground-, sea-, or air-launched.”

Griffin will focus on the “consolidation and … prioritization” of those projects to avoid duplication of effort and identify the most promising approaches, Shanahan said.

Roadmaps are being developed down to the system level. The KC-46 tanker has not yet been fielded, but a roadmap to improve the aircraft is already being built, according to Boeing KC-46 program manager Mike Gibbons.

Gibbons told a handful of reporters during the Boeing plant visit the KC-46 could be upgraded with new artificial intelligence and sensors to make the air refueling operation “autonomous,” which would make it possible to eliminate the boom operator position.

That position might not even have made it onto the first iteration of the KC-46, Gibbons reported, but the Air Force wanted to reduce risk on the project and did not want to introduce any changes to requirements that could add delay to the program. Autonomous refueling was demonstrated by Airbus last year on its A310 tanker, and the Navy’s new MQ-25 carrier-based tanker will be unmanned.

The Pegasus could also be fitted with new communications gear to fulfill a long-term Air Force idea to make it an “Internet provider in the sky,” Gibbons reported.