The End of Nuclear “Kick the Can”

The US can postpone modernizing its nuclear deterrent forces no longer. The triad of delivery systems, the warheads, the scientific infrastructure that builds and tests them, and the command and control system that ties it all together, have all long outlived their planned service lives. Now comes the task of convincing the public this massive recapitalization must somehow be afforded, among many other national priorities.

“We are out of margin, and we are out of time,” said retired USAF Gen. C. Robert Kehler, former commander of US Strategic Command, at a December MITRE Corp. seminar. “We have deferred modernization as long as we can defer it.” The last—partial—recapitalization of the nuclear deterrent was 30 years ago, and many of the systems, such as the B-52 bomber, are more than 50 years old.

A newly released RAND report—completed for the Air Force in 2018 but not publicly released until November 2019—warns the service must step up advocacy for strategic modernization or risk seeing existing infrastructure fail. RAND said the Air Force should spell out in detail its master plans for replacing land-based ICBMs, bombers, and the nuclear command and control (NC2) system, which is sometimes referred to as the “fourth leg” of the nuclear triad.

The “sheer scale of the programs is daunting, has not been performed at scale for many decades, and will need to be relearned,” said RAND.

The B-52 bomber, KC-135 tanker, AGM-86B Air-Launched Cruise Missile, and Minuteman III ICBM all date from the 1960s and 70s, Kehler said—well before the last modernization of the nuclear force. The information technology system tying it all together “aged out 30 years ago,” he said.

Meanwhile, Russia and China have “modernized—past tense,” Kehler stated. Their nuclear arsenals are fresh and the rapid buildup of the Chinese military has shifted the strategic landscape from a bipolar to multipolar world. “Further delay is just going to add risk,” he asserted.

Trillion with a ‘T’

The Congressional Budget Office said in 2017 that the cost of modernizing and operating the nuclear deterrent enterprise for the 30 years through 2046 would reach $1.24 trillion. Of that, $399 billion would fund buying or updating nuclear forces and $843 billion would fund operations and sustainment. Parsed another way, the Defense Department would spend $890 billion while the Department of Energy would invest $353 billion to support scientific infrastructure.

“This is not the Cold War,” Kehler said: The world situation is very different than when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. “We are facing a new set of uncertainties and global challenges that we have not faced before.” In addition to strategic nuclear weapons, the US faces cyberattacks and other threats “below the threshold” of a nuclear strike. That demands new strategy, new long-range conventional weapons, missile defenses, and assurance that the bedrock systems will all function properly when needed, he said.

Nuclear weapons underpin all other aspects of national security, Kehler said, and play a central role whenever diplomacy and military action are considered.

“In cases like Iran, [the threat of nuclear weapons is] being used by a country that doesn’t even have them,” he said.

Peter Fanta, deputy assistant secretary of defense for nuclear matters, said the US stopped designing, building, and testing nuclear weapons in 1992, “and the rest of the world did not.”

The weapons development complex was built in the 1940s through 1960s and has not been upgraded, he said. The engineers and scientists who designed the nuclear weapons built in the 1980s “are now retiring or dead.”

Demand Signal

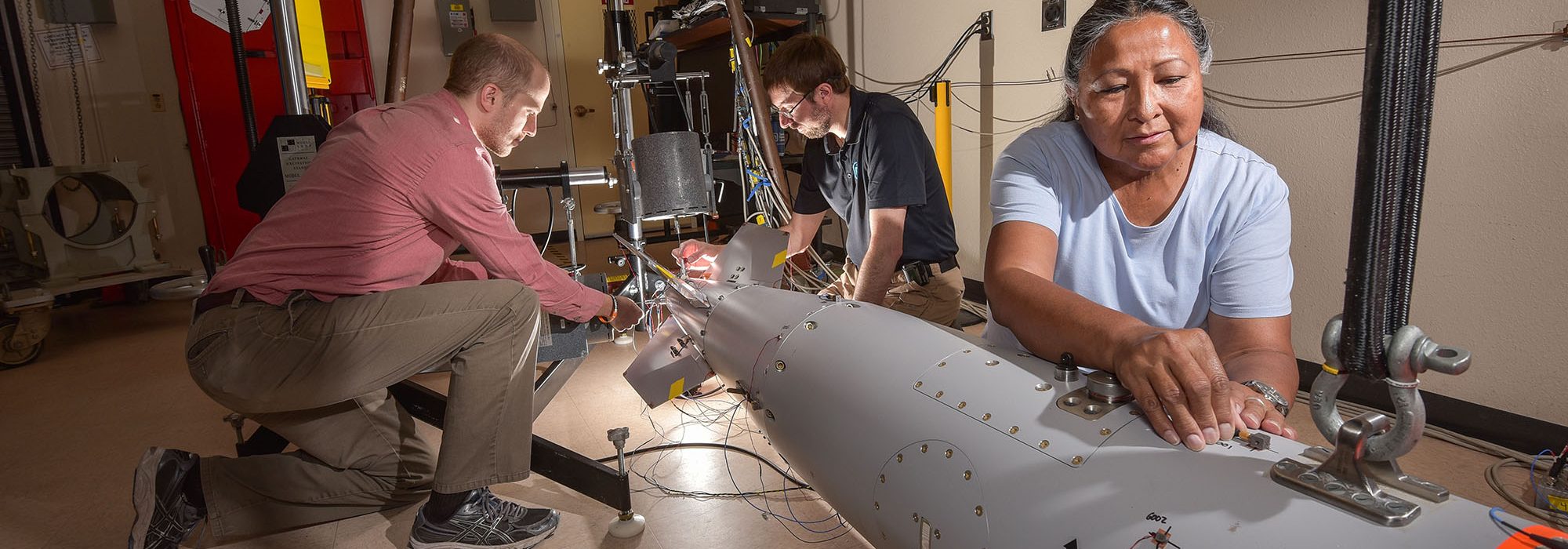

The US must build a minimum of 80 “pits” a year, referring to the core of a nuclear warhead, which resembles a peach pit, and is essentially a plutonium sphere surrounded by a reflective explosive shell.

“Why 80 pits per year? It’s math,” he said. “Divide 80 by the number of warheads we have—last time it was unclassified, it was just under 4,000—and you get a time frame,” Fanta said.

At only 30 pits per year, it would take until 2150 to upgrade the US nuclear stockpile—“after your children’s children are retired,” he said. The National Nuclear Security Administration says its facilities at Los Alamos, N.M., have the capacity for 30 pits a year, while those at Savannah River, near Aiken, S.C., have capacity for 50.

Exacerbating the problem is the question of how long each pit remains viable. Plutonium “is warm and, over time, it can deform what’s around it,” one expert told Air Force Magazine, and the plutonium itself will eventually transmute into uranium, devolving into “something that doesn’t produce the desired effect or expected yield.”

Fanta said, “There’s disagreement on whether they’re good for 100 years. … But we’re beyond that at this point. At 80 pits a year, we’ll have 100-year-old components by the time we replace those. … We need to stop arguing about it and get on with it.”

Swapped Doctrine

The US countered Russia’s overwhelming Cold War conventional advantages with nuclear weapons, Fanta said. Today, “the shoe is on the other foot.”

Russia is rapidly developing “underwater nuclear-powered weapons, hypersonic cruise missiles, and cruise missiles powered by nuclear reactors.” Why? “It’s a challenge for our conventional forces … an asymmetric threat,” Fanta said. “It’s our doctrine, swapped.”

The strategy, he explained, is a “reasonable way to rapidly close the gap against a larger, conventionally superior force.”

China, meanwhile, has also learned from watching the US. Still smarting over its inability to repel the US from the Taiwan Straits in the 1990s, China is now “outbuilding us 10-to-1” in conventional forces and “on the nuclear side, they are improving every capability they have,” Fanta said. That includes road-mobile ICBMs, advanced submarines, and ballistic missiles.

While “we’ve been discussing this for two decades, talking about pit production in the US, they were building,” Fanta continued. Now, to replace the Minuteman III with the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent will take “one GBSD missile built, shipped, installed, tested, and made operational every week for almost 10 years.”

The Navy’s Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines are also aging out. The Ohio-class subs, designed to serve 30 years, are being extended to 42 years, when they will be retired in favor of the new Columbia-class boats, according to the Congressional Research Service. But those “tin cans,” as Fanta characterized them, can only “squish back and forth” so many times under the pressure of deep submergence. “We need to … stop doing unnatural acts to keep the submarines going more than 42 years and start building now.”

The risks today are greater because none of the triad systems were upgraded in a timely fashion, said Deputy STRATCOM Commander Vice Adm. David Kriete.

“If we’re going to defend the country, we must remain a nuclear power,” Kriete insisted. “If we’re going to remain a nuclear power, that demands that we get on with our modernization plan right now.”

Air Force Lt. Gen. Richard M. Clark, director of USAF strategic deterrence and nuclear integration on the Air Staff, said James Mattis came into office as Defense Secretary in 2017 openly wondering whether a “dyad” of sub-launched missiles and bombers was sufficient. He left convinced that the triad is the right solution, concluding, “America can afford survival.”

The numbers matter, Clark said. Having 400 ICBMs compels an enemy to hit every one if a nuclear first strike is to be successful; without them, however, the US nuclear enterprise could be crippled “with about 10 strikes: You could take out our two sub bases, our three bomber bases, STRATCOM, the Pentagon, and our three labs … Los Alamos, Sandia, and Livermore.”

Hit those 10 targets and “our nuclear enterprise would be devastated,” he said.

Yet as dire as it seems, GBSD won’t be accelerated. “We are pushing it about as fast as we can go,” he said. Rather than accelerating GBSD, “We’re looking at every way we can to keep Minuteman III viable, reliable, and survivable,” Clark said. “You can only get so much out of maintenance; it’s such an old system.”

World War II-Era

Charles Verdon, deputy administrator of defense programs for the NNSA said aging infrastructure is not limited to weapons.

The NNSA is the nation’s nuclear weapons industrial base, having to “renew critical manufacturing facilities to ensure we have the materials necessary to ensure warhead delivery,” he said.

Yet, “Many of our critical facilities actually date back to the Manhattan Project.” Now, for example, the agency is trying to “put modern earthquake standards into a building built in 1945-1947,” according to Verdon.

A new building might be better, but it could take a decade for it to become productive.

The NNSA believes it needs to build 80 pits a year by 2030 to keep the warheads safe and “address the age of the systems that are presently there.” This number is deemed enough to “smoothly and methodically address the current pits/plutonium cores … over time, and respond to peer competition … or to meet a new military requirement,” he said. The longer the delay, though, the more pits that will be needed per year.

Making the Case

William LaPlante, former Air Force acquisition chief and now MITRE vice president for its national security sector, said the conference was designed to stimulate a national discussion on the need for nuclear modernization. To that end, it was cosponsored by George Washington University’s School of Media and Public Affairs.

“Since the fall of the Berlin Wall and certainly after 9/11, nuclear matters have not gotten much attention,” LaPlante said. “There deserves to be a better understanding by the American public.”

Frank Sesno, director of the GWU’s media school and a former CNN correspondent, said in past decades, when the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces and START treaties were major news events, “there was never a problem, as a reporter … getting a story about nuclear weapons or readiness or preparedness on the air or into print.”

That’s no longer the case, he said. Yet the public still needs to be engaged. “What is the investment? Toward what end?”

For Fanta, that end is clear: “Getting the entire nation to understand the world has changed, and we need to do things differently.” That’s a big challenge in itself, across the country and on Capitol Hill. “There’s change, there’s risks, and we need to address them.”