If the Air Force follows the advice of its top science advisors, it could move swiftly toward a stronger position in space in the opening years of the 21st Century.

About a year ago, Dr. Daniel E. Hastings, chief scientist of the Air Force, sketched the options in a report entitled “Doable Space.” Building on that, the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board in November produced a detailed “Space Roadmap for the 21st Century Aerospace Force.”

The Hastings report identified four “doable” paths. By 2012, it said, the Air Force can:

- Purchase most of its communications, imagery, and launch services as commercial commodities;

- Demonstrate the ability to deliver militarily significant amounts of laser energy through space to targets;

- Integrate its airborne and space-based assets to provide truly comprehensive Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance; and

- Move ground-based surveillance functions into space, where they command a far better view, and make satellites more survivable against attack.

The Scientific Advisory Board study was led by Dr. John M. Borky of TRW, vice chairman of the SAB and a major author of the landmark “New World Vistas” study in 1995. The roadmap generated no new operational requirements for space systems. Instead, it concentrated on recommendations to serve the needs laid out in such documents as the Air Force vision statement, “Global Engagement,” and the Joint Chiefs of Staff “Joint Vision 2010.”

Chart 1: Space Options vs. Time

|

By 2002, the roadmap said, the Air Force can have divested itself–at a considerable savings in cost–of numerous functions that are not essential parts of the Air Force mission and be well along with other programs, such as a new constellation of sensors, including a space-based radar, which might reach initial operational capability around 2008.

However, the roadmap said, current technology is not mature enough to support the demonstration of a space-based laser as early as some advocates—including several leading members of Congress–have urged.

“The study and the study team are not quarreling with the operational utility of this kind of military capability,” Borky said. “We think it would be enormous.” But, since “we are probably going to get one shot at doing it,” it would be a mistake to conduct the demonstration before technology will permit “very high confidence” of success, he said.

The Scientific Advisory Board also urged the Air Force to preserve the option to eventually develop an Aerospace Operations Vehicle.

“One possible outcome of our roadmap is a highly operable vehicle for both space and atmospheric missions at orbital speeds,” the SAB said. “With the appropriate payloads, the system would allow a photoreconnaissance mission, delivery of a precision weapon, or other ‘surgical’ effects delivery anywhere on Earth in something like 45 minutes from the ‘go’ order.”

Lt. Gen. Roger G. DeKok, USAF deputy chief of staff for plans and programs, said, “The studies produced by Drs. Borky and Hastings reinforce our conviction that integrating air and space will, in fact, yield a far more capable instrument of national military power, not just a more effective or efficient version of today’s Air Force.”

Shift to Commercial Space

A major theme of both studies is that commercial space will loom increasingly large in the Air Force space program. There are three main reasons for this.

First, the overwhelming share of growth in space is by the commercial sector. By 2010, Hastings says, military launches will account for a mere 6 percent of the total. Second, the technology surge in space is being led by the commercial world, which develops new capabilities far better and faster than the government could hope to do on its own. And third, the Air Force can save a great deal of money by relying on the commercial market for many of its needs, including most space launch needs.

The SAB said that commercial space services “will have an aggregate capacity early in the next century that is about 1,000 times that of even the most ambitious MILSATCOM structure,” and it urged that the Air Force phase out, as early as it can, “non-core” military satellite communications in favor of commercial services and interoperable user terminals.

The roadmap went considerably further on privatization, though. It recommended that the Air Force divest itself of the Eastern and Western Ranges, which could be operated on a commercial contract and overseen by a suitable civilian agency, such as a National Space Port Authority.

At present, Air Force funding–which covers 90 percent of all launch costs at the two ranges–constitutes a subsidy for all users. In the near future, government launches will account for only 6 percent of total launches, Hastings said. If the Air Force was a customer and tenant rather than operator of the ranges, it could not only concentrate better on its core mission but also save considerable money.

Eventually, the Air Force should rely primarily on commercial launchers for putting payloads into space. “In the long term,” the roadmap said, “one or more of the several advanced launch technologies under consideration is likely to make access to space very cheap, perhaps one-tenth to one-hundredth the cost of today’s operations.”

New Constellation of Sensors

Today, the SAB said, “Intelligence satellites and airborne platforms provide localized and generally discontinuous sensing, often impeded by weather, terrain, and hostile countermeasures.” These systems cannot provide the kind of global awareness prescribed by “Joint Vision 2010.”

The roadmap said that the Air Force should commit to a new sensor satellite constellation to complement existing Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance platforms in air and space. This constellation would be able to track moving targets on the ground. The primary payload would be a space-based radar, with initial operational capability in about 2008 and full operational capability between 2010 and 2012.

“Joint force commanders, especially in deployed operations, are going to need all-condition, responsive, high quality sensing with the results delivered sensor-to-decider-to-shooter in near real time,” Borky said. “A space-based radar system designed primarily for direct support to theater operations could do that, and would be a powerful complement to other sources, such as air-breathing platforms, national intelligence systems, and commercial imagery, each of which has limitations on what it can do directly for a warfighter.”

An additional sensor in the constellation would perform hyperspectral imaging, reading the light reflected by objects and seeing thousands of different colors. That capability will be particularly effective in detecting use of chemical or biological agents and in countering camouflage, concealment, and deception tactics.

“You can, for example, find objects hidden under trees,” Hastings said. “If sunlight can get through the leaves, you can tell the difference between a leaf and a tank under [the] tree because the light reflected looks different from a hyperspectral image, [although] to us it may not look different.”

As the surveillance of space improves, it will become possible to develop what the roadmap called a “recognized space picture.” Today, the Intelligence Community produces a “Common Operating Picture,” consisting of air, maritime, and ground elements. It gives theater commanders information about what is happening in the theater battlespace in a detailed and current package.

Similar information from space is not included, Borky said, because we do not have the capability to surveil space with “the same timeliness and completeness and fidelity as we surveil the air, ground, and sea.”

A large part of the surveillance of space is presently done by aging sensors on the ground. There is some merit in updating these ground stations, but the roadmap said the Air Force “should migrate selected space surveillance functions to space.”

An early move might be to modify the low constellation of the Space-Based Infrared System, enabling it to look up and track objects in high orbits as well as carry out its primary mission of missile launch warning, in which SBIRS looks downward.

The roadmap also recommended that the Air Force pursue improvements in the position, navigation, and timing information provided by the Global Positioning System. Since its introduction in the Gulf War, the popularity of GPS has spread like wildfire. It is now used by fishermen and rescue squads in addition to the original military users. Even so, because of the importance of GPS, the Air Force should retain control of it on behalf of the Department of Defense, the roadmap said, but it added that funding contributions from other agencies and sources would be “appropriate.”

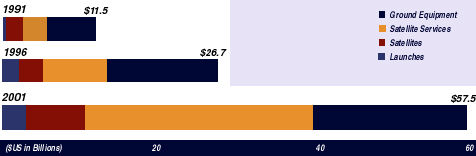

Chart 2: Growth of Commercial Space Worldwide |

| Source: Space Roadmap |

|

Lasers Through Space.

The global projection of energy through space to targets was one of the four main thrusts of the Doable Space study, but Hastings stopped short of forecasting a space-based laser. Both his study and the roadmap spoke instead of projecting laser energy from or through space, meaning that some or all of the weapons might be located on the ground.

The issue is complicated by the fact that deployment of a space-based laser, a prime use of which would be ballistic missile defense, is presently prohibited by the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. On the other hand, there is strong support in Congress for the space-based laser, and last year’s defense bill called for on-orbit testing of a “readiness demonstrator” by 2005 or very soon thereafter.

The roadmap said that the current technology, a chemical laser system designed in the 1970s, is not mature enough to support such a demonstration and that “fixes” to the existing system will not bring it up to snuff. More work is needed in system engineering and integration, beam and fire control, and other areas. Alternatives to chemical lasers–including electrically powered solid state lasers–should be explored.

The SAB recommended that the Air Force not proceed with the readiness demonstrator test “at this time.” The roadmap said technology should be pursued “aggressively” and that it would be advisable to first conduct a ground demonstration program of the laser and decide, around 2003, whether to commit to an on-orbit test.

Borky emphasized that the SAB’s reservations are about the current technology, not about the desirability of the system. The roadmap agreed with previous studies that “directed energy from space, whether generated in space or relayed from the air or ground, will be a major weapon capability in the next millennium.”

Possibilities of such a system go beyond shooting down ballistic missiles with a laser beam from space.

“A high-energy force projection system could contribute to a wide range of missions, including counterair, space control, and missile defense,” the roadmap said. “It could also deliver a range of effects-from active optical sensing modes to disruption of optical systems-to the Earth’s surface with exquisite precision.”

In December, F. Whitten Peters, acting Secretary of the Air Force, told the Defense Writers Group that the Air Force will not rush the space-based laser program. “Many on the Hill believe that a space-based laser is a piece of cake and that the costs are fairly low,” he said. “Our view is that it is a very difficult technical challenge.” The deployment of large optics in space “is a technology that just isn’t here yet. It is one that is coming, that several different groups are working on.” The Air Force believes that it “could reasonably try to deploy something in the 2010 time frame, and we are working on that plan.”

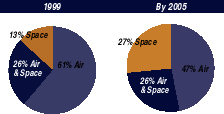

Chart 3: Air Force Technology Funding |

|

|

The Air Force plans to double the share of science and technology funding allocated to space, hold the share constant for technologies that apply to both air and space, and reduce the percentage for R&D unique to air. Total for the three categories in 1999 is about $1.3 billion. |

The Aerospace Operations Vehicle

The SAB said the Air Force should “preserve the option” to develop an Aerospace Operations Vehicle which could be launched from Earth, fly through space at hypersonic speeds, and perform its mission either from space or by re-entering the atmosphere.

This is a continuation of the concept that has been known variously over the years by such names as “aerospace plane” and “transatmospheric vehicle.” These proposals generated a great deal of excitement but fell away because of technology and funding problems.

In some versions, the vehicle would have taken off from Earth under its own power, but the main concept presented in the roadmap is a two-stage-to-orbit system “with a family of upper stages, each compatible with a variety of expendable boosters and with a relatively low-speed reusable first stage.”

The Air Force continues to work with NASA to explore a space operations vehicle. NASA has been working on reusable boosters, while the Air Force has concentrated on a several kinds of upper stages, including a “Space Maneuvering Vehicle” for operations on orbit and a “Common Aero Vehicle” for delivery of payloads in the atmosphere.

The AOV concept, the roadmap said, “is one way to achieve highly responsive launch (defined in this study as less than 24 hours to integrate, prepare, and launch a vehicle and payload), creating the possibility for the first time of spacecraft operations with a sortie rate analogous to that of heavy aircraft, depending on the requirements placed on the first stage of a two-stage system.”

Both cost and technology point toward expendable launch systems, but the roadmap did not rule out single-stage-to-orbit concepts. The AOV would have to fly about once a week to spread the costs over enough launches to make the expense of a reusable launch vehicle competitive with expendable launchers.

The SAB said the Air Force should continue with its Space Maneuvering Vehicle demonstration, which costs about $35 million a year, to keep its options open. “If the results of technology demonstration and operational analysis are favorable at a decision milestone in about 2002, [the Air Force should] start a follow-on program leading to a first demonstration flight in about 2009 and an operational AOV in about 2015.”

How to Fund It

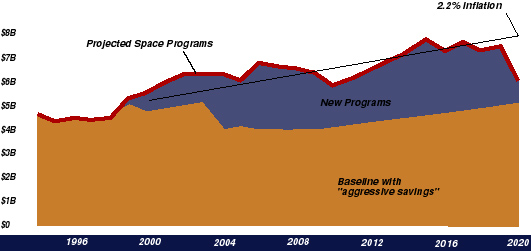

Depending on what is included in the calculation, the present cost of the Air Force space program is about $7 billion a year (out of an annual budget of about $75 billion). Of that, about $4.1 billion is for “investment” accounts-new systems and procurement-with the rest going for operations and maintenance of existing systems. The roadmap focused on investment spending and projected the current budget level forward for 20 years, adjusted for 2.2 percent projected annual inflation.

The shortfalls in that projection begin almost immediately. The funding in 2001 and beyond does not even cover the present baseline program, much less the initiatives and improvements proposed in the roadmap.

To some extent, though, the roadmap is self-funding. The SAB said that “conservative savings” (roughly $2 billion to $3 billion per year) can be achieved by implementing recommendations in areas of launch and tracking ranges, communications, and satellite operations. The study expressed “high confidence that our recommendations will produce at least this level of cost reduction.”

“Aggressive cost reductions” might reduce still more the baseline of the present program, projected out to 2020 and adjusted for inflation, bringing the topline of the space program–the new programs and initiatives as well as the existing program–“back into rough balance with the current top line.”

Even those measures do not fund everything in the roadmap, though, and if annual inflation exceeds 2.2 percent, the shortfall gets worse.

“We recognize that most of the economy measures will have substantial organizational impacts and will meet with resistance,” the roadmap said. “In the aggregate, actions such as outsourcing launch and satellite control operations, winding down a number of MILSATCOM systems, and phasing out legacy tracking systems will affect thousands of manpower positions and large fractions of the current budgets of the affected units.”

Noting that “the Air Force faces huge budget problems in space (and almost everywhere else) whether this study’s recommendations are acted on or not,” the SAB said that “there is no way out of this dilemma that does not involve both changing fiscal priorities and divesting large pieces of today’s Air Force mission and infrastructure.” The SAB said, for example, that “thousands of military manpower authorizations that are now dedicated to support activities in space system and launch operations can be replaced with a far smaller workforce, largely contracted out,” and the personnel can be “moved to fill urgent needs elsewhere. This would be consistent with the development of a corps of aerospace warfighters, skilled in all the dimensions of applying spaceborne and airborne instruments of national power.”

Reality may mean “breaking the mindset that each program area in the Air Force budget has a ‘fair share’ percentage which cannot be changed by other than trivial amounts,” the roadmap warned. “Total Obligation Authority (TOA) will probably have to be moved into the space area from other programs, at least in some years of high space activity.”

Chart 4: The Yield From “Aggressive Savings” |

|

|

|

| The space investment account is about $4.1 billion a year. Projected into the next century and adjusted for inflation, that amount would double by 2020. That level, however, will not be enough to fund baseline programs, much less any of the new ones proposed. “Aggressive savings,” achieved by implementing strong recommendations proposed by the roadmap, might lower the cost of the baseline programs to about $5 billion in 2020, some $3 billion below the projection without such savings. In many years-and in every year through 2008-there is still a shortfall. If the inflation rate is higher than 2.2 percent, the shortfall gets worse. |