Hurricane Hunters with the Air Force and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration are struggling to keep up with a rising number of storms, but a government watchdog says both agencies need to refine their data-tracking efforts and improve interagency communication between its most senior leaders to develop a cohesive plan forward.

“Developing a process to track these data would help the agencies better understand the challenges their Hurricane Hunter missions face and identify actions they could take to reduce missed mission requirements and improve operations,” the Government Accountability Office wrote in a report that was publicly released March 14.

Hurricane Hunters fly into storms to collect atmospheric data that help scientists at the National Hurricane Center predict the size of the storms and where they will make landfall, which in turn helps decision-makers make calls such as evacuation orders.

Giving forecasters better data saves lives and money; it costs at least $1 million to evacuate a mile of coastline, so it helps when planners have a better sense of where to focus safety efforts.

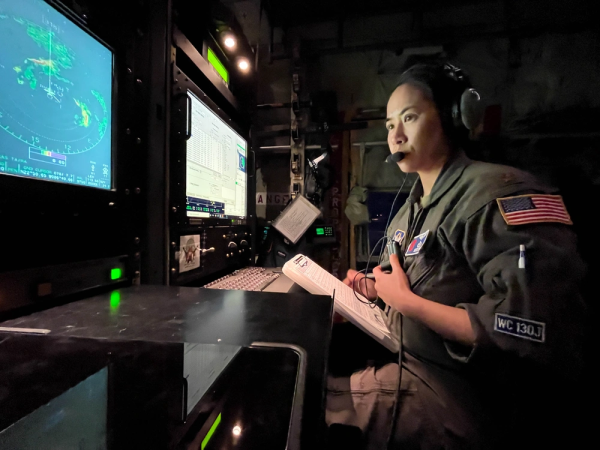

On the Air Force side is the 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, a Reserve unit that flies 10 WC-130J aircraft out of Keesler Air Force Base, Miss. Meanwhile, NOAA flies two propeller-driven WP-3D Orion aircraft and one Gulfstream IV jet for high-altitude missions above storms.

None of the aircraft are spring chickens: the WC-130Js entered service in the late 1990s, the Gulfstream in 1994, and the Orions in 1974 and 1975. Flying into storms wears out aircraft faster, and maintenance issues have cancelled critical missions.

It doesn’t help that the Hurricane Hunters’ workload is rising every year: 2019 to 2023 saw 36 percent more tropical cyclone missions than 2014 to 2018. During the winter months, the Airmen fly to the West Coast to gather data on atmospheric rivers. They were nearly 13 times more busy during the winters of 2020 through 2024 than they were between 2015 and 2019, but their staff and equipment resources have not kept pace.

“NOAA’s air crews are thinly staffed with limited backup options … NOAA’s Hurricane Hunter maintenance personnel told us that they have been thinly staffed for years, resulting in unsustainable heavy workloads that have contributed to greater burnout for personnel,” GAO wrote. “According to NOAA officials, the agency is often one illness or injury away from having to cancel missions.”

In August, NOAA had to delay its Gulfstream by two days during the early stage of Hurricane Ernesto because no backup staff were available when a dual-hatted flight director and in-flight meteorologist had to attend to a family emergency.

The Air Force is in a similar spot, with some crew members juggling civilian careers in addition to their military duties. The 53rd WRS missed a few mission requirements during the 2023 tropical cyclone season because its air crews were burned out, GAO noted.

Mission Requirements

Mission requirements refer to key hurricane hunting objectives such as dropping instruments called dropsondes into storms, which gather forecast data for scientists. Mission requirements might be missed due to mechanical or staffing issues, and when that happens it reduces the accuracy and confidence of forecasting decisions, which can lead to larger, more disruptive, and more expensive evacuations.

The number of missed requirements during the tropical cyclone season is on the rise, with about 6 percent missed from 2014 through 2018 on average and 9 percent from 2019 and 2023. The winter season is more difficult thanks in part to icing and limited maintenance capabilities on the West Coast, contributing to a nearly 30 percent miss rate on average since 2020.

But while it’s clear that the Hurricane Hunters are missing requirements, it’s not exactly clear why. GAO noted that neither NOAA nor the Air Force systematically tracks the reasons why they miss mission requirements. NOAA said it historically has not tracked the reasons because in the past mission requirements happened so infrequently. The Air Force did not track that data because they were not required to and did not consider it a priority, officials said.

GAO believes in evidence-based policymaking, so it recommended the two agencies start tracking that data to inform better solutions. The agencies agreed, and in September they started developing a system to synchronize rather than duplicate each other’s efforts.

“By working together to develop and implement a systematic process to track these data, NOAA and the Air Force would have the information needed to better understand the challenges facing their Hurricane Hunter operations so that they can identify and take actions to improve their ability to complete requirements,” GAO noted.

Comprehensive Communication

The same lesson applies to NOAA’s and the Air Force’s staff and workforce structure. It’s clear that both agencies’ Hurricane Hunters are over-worked, but neither agency has completed a comprehensive assessment of its workforce, GAO wrote.

For example, NOAA hired a contractor to assess its pilots and navigators in 2024, but the assessment did not include its other air crew, aircraft maintainers, and other employees. The 53rd WRS also lacked such a comprehensive study.

“Comprehensively assessing their Hurricane Hunter workforces would help inform efforts by NOAA and the Air Force to ensure that they have the appropriate staffing levels and workforce structure in place to meet the growing demand for Hurricane Hunter missions,” GAO wrote.

Besides more thoroughly assessing their operations, the two agencies also need to improve their high-level communications, GAO said. The two groups work closely together at the operational level and below, filling in for each other’s missions, holding lessons-learned meetings every year, and putting on an interagency aerial reconnaissance equipment working group to prioritize new technologies.

But decisions affecting long-term investment and strategy require senior leadership, and GAO noted a lack of communication between the most senior officials.

“Senior NOAA officials said they have tried unsuccessfully to reach out to the Air Force about its plans for its Hurricane Hunter aircraft and stated they were unsure which Air Force leaders they should communicate with on this topic,” the office wrote. “In the absence of such communications, the officials said they do not know what the Air Force’s long-term plans are for its Hurricane Hunter aircraft, which has made it more difficult for NOAA to determine the needs and requirements for its own aircraft recapitalization efforts.”

One senior NOAA leader likened it to building two halves of a house separately without discussing how the plumbing, wires, or other systems will connect with each other.

Upgrades

Better communication could lead to better-coordinated recapitalization efforts. NOAA plans to replace and expand its aircraft fleet with two new Gulfstream jets and four C-130Js. The 53rd WRS has no immediate plans to replace its WC-130Js (which are also aging quickly), but it does want better communications bandwidth and Wi-Fi so that Airmen can transmit more data mid-flight rather than wait until the aircraft lands.

“Air Force officials described the process to make modifications to the Hurricane Hunter aircraft, such as installing new technologies or equipment, as cumbersome and slow,” GAO wrote. “ … It can take years, in some cases more than a decade, for the Air Force to add new capabilities to its aircraft.”

Like with the other resource problems, the need for change is clear, but GAO said the Air Force needed to identify specific system improvement barriers and develop mitigation plans.

In his response to the GAO report, Lt. Gen. John P. Healy, the head of Air Force Reserve Command, said his troops had stood up a WC-130J Requirements Working Group to refine the aircraft upgrade process even before the GAO’s assessment.

“As this process continues to mature, Air Force Reserve Command will identify and support changes to improve processes both within the command as well as with their mission partners,” Healy wrote.

Both NOAA and the Air Force concurred with all of GAO’s recommendations.