AURORA, Colo.—Looming cuts to the Pentagon’s civilian workforce will present a particular challenge to the Space Force with its proportionally high number of civilian Guardians, leaders said at the AFA Warfare Symposium.

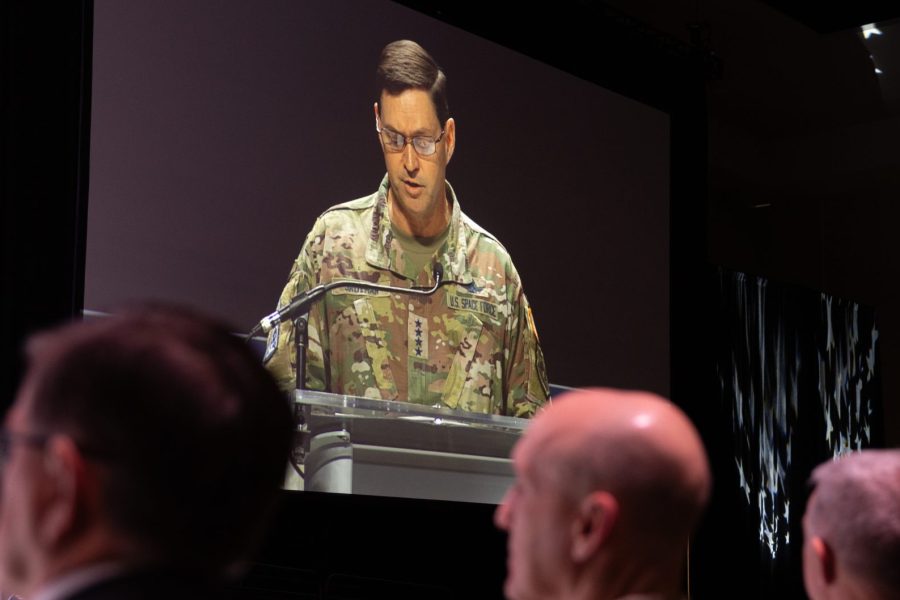

Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman said he is considering the impacts of the personnel cuts being directed by the Trump administration to shrink the size of the federal workforce.

More than 4,000 of the Space Force’s 14,000 members are civilians—nearly three-tenths of the service.

“The orders are pretty clear, and we’re going to follow those orders,” Saltzman said. “Am I worried about it? I’m always worried about making sure we have the right workforce to do the missions that we’ve been given.”

He’s not the only Space Force general thinking about it.

A “considerable number” of civilian employees of the Space Force’s main acquisition arm, Space Systems Command, had opted to take the “deferred resignation” option offered by the new administration, said SSC commander Lt. Gen. Philip A. Garrant. Under the offer, devised by Elon Musk and his Department of Government Efficiency commission, federal employees can stop working now but be placed on administrative leave and continue to get paid until the end of September. The terms are designed to entice as many people as possible to accept the offer.

“As the commander of SSC, I’m committed to executing the administration’s direction and vision,” Garrant said, adding that he was “working really closely with our S-1 Human Resources team to do it smartly where we can, and to make sure that we’re not making workforce cuts in strategic career fields and areas.”

On Feb. 26, the Department of the Air Force said in a memo that some of those who had opted for deferred resignation—those in hard-to-fill positions or with special skills or whose work was particularly vital—would be deemed “exempt or ineligible” for the program. Those positions included flight instructors, those in certain cybersecurity jobs, and Foreign Military Sales personnel. The department also instituted a hiring freeze.

Garrant said he also had a number of probationary civilian employees who were likely to be let go “just like they have in other departments.” Probationary employees don’t enjoy the same legal protections as fully fledged federal staff and can fired more or less at will.

He also noted that the Office of Personnel Management had ordered a “reduction in force” of the federal government.

Although he didn’t give numbers, Garrant said that the potential impact of all these measures on the SSC civilian workforce “is in line with what you’re seeing and hearing from a total federal government reduction of the federal workforce on the civilian side.”

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth has said he anticipates cutting the Pentagon civilian workforce by 5 to 8 percent. Applied to the entire Space Force, that would be a few hundred people.

While the staff reductions loom, the Space Force—along with the rest of the federal government—is still operating under a continuing resolution (CR) and doesn’t have a 2025 budget.

“We have to have a budget,” Garrant said, “A yearlong CR would just exacerbate the federal workforce issues with some agencies.”

He said that these “additive challenges” had combined to create “a very stressful time, mostly because [they’re] all on top of each other.”

But Saltzman pointed out that the Space Force “was designed to be lean and agile.”

“We’ve been doing the mission for five years with far less people than we have today, and by and large, you still get GPS when you turn your phone on.” He called the service’s achievements with such a limited headcount “pretty impressive.”

“The workforce ebbs and flows,” he concluded, “In my 33 years, I’ve seen several of these issues, and you just reprioritize and do what you’ve got to do.”