The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency is looking for “revolutionary” ways to protect from hackers that workhorse of modern computing, the data bus, a standardized component that allows different pieces of IT equipment—including those in aircraft and weapons systems—to communicate.

The cable that lets your keyboard or mouse plug in to any computer on the planet is a data bus—the Universal Serial Bus, or USB. Other kinds of data buses offer critical connections between a computer’s brain, the Central Processing Unit or CPU, and peripherals like a graphics card or solid state drive, explained Bernard McShea, a program manager in DARPA’s Information Innovation Office.

“They’re everywhere,” McShea told Air and Space Forces Magazine. They’re also extremely convenient, said other experts.

“If I plug it in, it’s going to work. That’s great! But that also means that everything I plug in is going to work, including the bad stuff,” said Daniel Genkin, associate professor of cybersecurity and computer science at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Data bus standards typically don’t include any validation of inputs or authentication of data, but instead implicitly trust the devices they’re connected to.

“From a security point of view, that’s not ideal,” noted former NSA Technical Director for Weapons and Space Cybersecurity Pat Arvidson.

Despite this, data buses are part of the increasingly sophisticated control systems that run cars, aircraft, and even IT networks. The MIL-STD-1553 data bus, which is used ubiquitously in U.S. and NATO aircraft, vehicles and weapons platforms, has long been a focus of concern.

Arvidson, now cofounder and CTO of Risk Aperture, a cybersecurity assessment firm, said the vulnerabilities of data buses and their widespread use in weapons systems and platforms like aircraft are a source of concern at the Pentagon. “How do you validate those inputs? … We worried about that a lot,” he said.

DARPA last month asked industry and academic researchers to submit research proposals for its program, Reclaiming Bus-based Systems During Compromise, or Red-C, to “investigate innovative approaches that enable revolutionary advances” in the security of one kind of data bus, the PCIe.

Traditionally, security wasn’t a priority when writing data bus standards because to get at the bus, a hacker would have to have physical access to the machine, said Genkin, who worked on some preliminary research for Red-C and whose institution may submit a research proposal for funding from the program.

“The historic security assumption there was that, hey, if I have physical access to your computer, then there is a lot of mischief I can get up to, so no need to worry about the bus. The problem is that more and more we’re exposing these buses” to external links, said Genkin.

He gave as an example a phone charging station at the airport. “You will plug in because you want power to charge your device. But the standard allows data, too. So by [plugging in] you just gave me access to your USB bus.”

“I can declare myself a keyboard and start typing. I can monitor all your typing,“ Genkin said. Because most buses follow the implicit trust model, “if you have access to one of these buses, [even online] you can hack whatever is connected to that bus, take it over.”

And the vulnerability of data buses is much more than a consumer issue, argues Arvidson. Adversary nations can use the vulnerable bus architecture as a weapon of war.

“If I understand that architecture, I can create a waveform, traditional electronic warfare, and on that wave form I’m going to put malformed data that the sensor on that aircraft is going to pick up,” he said. And because there’s no authentication on data buses that malicious data will be believed and acted upon just like the real thing would be, he added.

Judging the risk of an attack like this, Arvidson said, involved assessing a range of possible scenarios and outcomes.

“The most likely scenario, the pilot sees there’s a problem with the instruments, aborts the mission, flies home, and they have to stand the aircraft down until they can figure out what happened. The most dangerous scenario is a weapons mishap” like the unintended release of airborne munitions, or a submarine firing a torpedo when the hatch is closed, Arvidson said.

Securing data buses is the kind of difficult problem DARPA was set up to address, he continued. “They’re very smart to start with the PCIe bus, because they’re scaling down the bigger problem. It’s an edible-sized piece of the elephant,” he said. More sophisticated buses, like the MIL-STD-1553, presented even harder problems.

One issue is, you can’t just add authentication, Genkin said: “You add layers and layers of complexity once you start asking the questions: What data is allowed on there? Who is allowed to send data? And to whom? Who is allowed to access which data?”

And all that complexity can add computing overhead and latency to systems which are designed to be quick and nimble, he said.

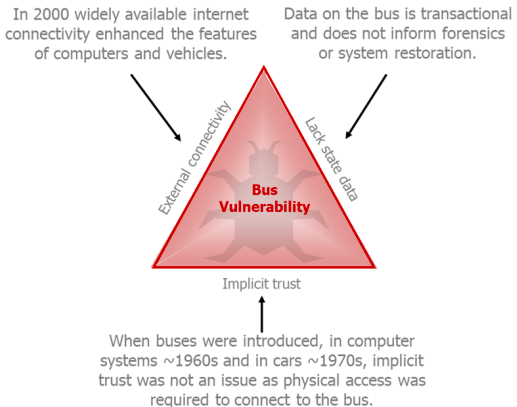

McShea jokingly referred to data buses as being trapped in the “triangle of doom”:

- Implicit trust means no security checks on data or devices

- More and more access to data buses online

- No logging or “good state” data

McShea explained the approach DARPA’s initial research had opened up, although he stressed he didn’t want to close off any other approaches: “In our [preliminary research] we were able to rewrite the firmware [in components connected to the bus], to instrument them as forensic sensors” to gather data, he said. The data would reveal when traffic across the bus was being tampered with. “We were able to detect ransomware attacks effectively,” he said, with only a six percent computing overhead.

McShea likened the data gathering by the bus-connected components to a neighborhood watch, with multiple components watching each other: “Each component has its own local perspective, and then when you combine them all, the combination gives you a global perspective,” he said.